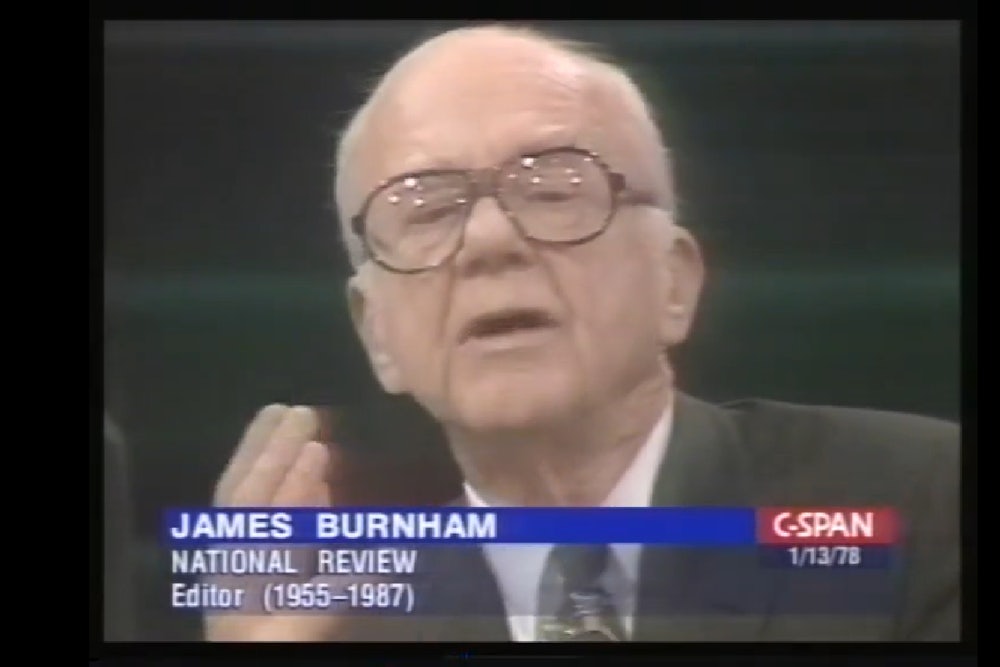

When James Burnham, a founding editor of National Review, died of cancer in 1987, he seemed destined to be utterly forgotten. Samuel Francis, the paleoconservative who had written a monograph on the Marxist-turned-conservative and was his chief intellectual heir, wrote in the The World & I magazine, “A reticent man by nature, Burnham by the time of his death was not well known in either the national intellectual community or even in the conservative movement with which he had worked since the 1950s, and many today who are pleased to call themselves conservatives confessed their ignorance of who he was or what he had done.”

Three decades later, quite the opposite is true, as an increasing number of thinkers who are pleased to call themselves conservatives profess their knowledge of Burnham and what he did for the conservative movement. They’re holding up Burnham as an alternative to Trumpism, portraying him as an advocate of a measured, brainy, and pragmatic right-wing politics that seeks to shape elite institutions rather than to take populist delight in burning it all down.

Addressing “the crisis of the conservative intellectual” in a lengthy essay earlier this month, Washington Free Beacon editor Matthew Continetti argued that conservatives must “rehabilitate Burnham’s vision of a conservative-tinged Establishment capable of permeating the managerial society and gradually directing it in a prudential, reflective, virtuous manner respectful of both freedom and tradition.” Back in August, Continetti was even more explicit, tweeting:

James Burnham would have been disgusted by Donald Trump. Supported Rockefeller in 1964. https://t.co/zlYnJxQ35r

— Matthew Continetti (@continetti) August 26, 2016

Building on Continetti’s column, Ross Douthat acknowledged that there is appeal to returning to Burnham’s path, although he fretted that a strategy of focusing on converting liberal elites would be arduous and possibly fruitless. But the New York Times columnist also found merit in Burnham’s core idea of “managerial revolution,” which Douthat repurposed to denounce “the largely liberal meritocrats who staff our legal establishment, our bureaucracy, our culture industries, our universities.” In a more sentimental vein, fellow Times columnist David Brooks has taken to waxing wistfully about the intellectual giants of his youth. “When I joined National Review at age 24 I joined a very self-conscious tradition,” Brooks fondly reminisced in March. “I was connected to a history of insight and belief; to Edmund Burke and Whittaker Chambers and James Burnham.”

In times of crisis, nostalgia can be a haven. So it’s not surprising that as Donald Trump continues to be a wrecking ball destroying conservative orthodoxy, many leading right-wing pundits have tried to find what comfort they can by leafing through the pages of dusty tomes written by the luminaries of old, the wise men (and it’s usually men) who laid the foundation for American conservatism. But these writers’ high regard for Burnham is misguided—not only overripe with nostalgia but deficient in historical understanding.

Burnham was a deeply incoherent thinker, sympathizing at various times with such disparate historical figures as Leon Trotsky, Charles De Gaulle, Joseph McCarthy, Nelson Rockefeller and Robert McNamara. Torn asunder by competing elitist and populist impulses, he never achieved a stable synthesis of these competing impulses, so he leaves no usable legacy—certainly not as an alternative to Trumpism. If anything, Burnham was a precursor to Trump, or perhaps more accurately, prefigured the divide within the Republican Party that Trump has exploited.

The intellectual lineage connecting Burnham to Trump was well laid out by historian Timothy Shenk, a fellow at the New America Foundation, in The Guardian in August. Shenk traced the intellectual origins of Trumpism to a “dissenting minority” of conservative thinkers that runs from Burnham to paleoconservative Samuel Francis. The hallmarks of this tradition are ultra-nationalism as evinced by a unilateralist foreign policy, protectionist trade policy, and support for immigration restriction. This ultra-nationalism is deployed in the service of a submerged white working class in revolt against a managerial over-class. Shenk’s analysis is exceptionally astute, but it can be usefully augmented by a review of Burnham’s life.

Born in Chicago in 1905 as the son of a wealthy railroad executive, James Burnham seemed destined to be part of the American elite. He excelled as a student at Princeton and Oxford, earning a professorship in philosophy at New York University when he was only 25. William Barrett, Burnham’s colleague at New York, recalled that he “bore the stamp of the gentleman in his bearing—so much so that in comparison with some of the more raucous types of the New York intellectual he appeared almost shy and diffident.”

But the Great Depression made Burnham a paradoxical figure: a patrician revolutionary. He became a Marxist, active in the Workers Party (a Trotskyist formation and the precursor to the still existing Socialist Workers Party). Throughout the 1930s, Burnham was a divided figure: helping organize plebeian protests even as he and his wife Marcia continued to throw elegant dinner parties. Despite the contradiction, Burnham rose high in the ranks of the party and came to be highly esteemed by Trotsky himself, until the two men quarreled over the nature of the Soviet Union. For Trotsky, the Soviet Union was a “degenerated” workers’ state, still deserving defense by socialists. Burnham rejected this view as he grew appalled by Stalin’s cynical foreign policy (especially after the 1939 pact with Hitler) and domestic tyranny. It was a painful controversy since Burnham much admired Trostsky, who denounced his follower as an “educated witch doctor.”

After Burnham broke from the Workers Party in 1940, he wrote his most famous book The Managerial Revolution (1941), an ambitious attempt to forge a post-Marxist social theory. Burnham argued that the Soviet Union was a new type of society but not a socialist one. Rather, the Soviet Union, along with Nazi Germany and New Deal America, pointed to a future where capitalism would be supplanted by a fusion of the state with big business, controlled by the managerial class. Under capitalism, power was held by those who owned the means of production, but under the new managerial system power would be wielded by technocratic experts. No longer would businessmen follow the rags-to-riches trajectory of Andrew Carnegie; instead they would have MBAs and employ a stratum of middle mangers who were similarly educated, sharing the same class profile as government bureaucrats. (Contra Douthat’s gloss, Burnham always located the American form of the Managerial Revolution in corporate power, and didn’t see it as being necessarily liberal.)

In a subsequent book, The Machiavellians (1943), Burnham argued that while the socialist dreams of equality were impossible and democracy itself was a sham, a measure of freedom was still possible in a managerial society if it allowed for a “circulation of the elites.” That is to say, an American-style Managerial Revolution, with freedom of speech ensuring the possibility of critique and the rise of talent, allowed for at least the “minimum of moral dignity.”

These two theoretical books help prefigure Burnham’s rapid move to the right in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1943, Burnham joined the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime spy agency, where he wrote an influential memo arguing that America should prepare for a postwar world where the USSR was its primary enemy. Burnham recast his memo as The Struggle for the World (1947), which argued that the only alternative to a Soviet world conquest was the creation of an American global empire. In effect, Burnham took Trotsky’s idea of a world revolution and inverted it, with Washington taking the place of Moscow as the spearhead of a push for a global government. A cornerstone text of conservative foreign policy thinking, the book established Burnham as one of the leading hawks of the Cold War, someone whose advocacy of rolling back communism stood in contrast to George Kennan’s more establishment policy of containment.

Nor was Burnham merely a theoretical Cold Warrior. He was active in the Central Intelligence Agency from 1949 to 1953 (and more informally for decades thereafter) in the Office of Policy Coordination, the agency’s covert operation wing. In that capacity, he was involved in some of the most disturbing and disgraceful acts of American foreign policy, notably helping organize the 1953 coup that overthrew the democratically elected government of Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran.

In The Machiavellians, Burnham styled himself a realist. George Orwell, a persistent critic of Burnham, was more accurate when he wrote in 1946 that “Burnham’s writings are full of apocalyptic visions.” Writing in The New Republic in 1987, John Judis argued that “Burnham bequeathed a divided legacy of fantasy and realism.”

Orwell and Judis were too kind, since Burnham was wildly wrong more often than almost any thinker of the twentieth century.

Burnham’s litany of mistakes is astonishing. In 1941, he argued that Germany was sure to defeat the Soviet Union. In 1943, he predicted that “there will almost certainly be a terrific economic crisis after the end of the present war.” Throughout the Cold War he claimed that the failure to roll back communism would lead the Soviet Union to get the upper hand. In 1953, he wrote that the Marshall Plan had failed to create “a situation of socioeconomic strength” in Western Europe. He adamantly opposed the decolonization of Asia and Africa, arguing that the world was best served by a continuation of European domination. He justified the war in Vietnam on an extreme version of the domino theory, saying a loss there would lead America to retreat back to Hawaii. He also wanted America to use biological and chemical weapons in Vietnam.

From the late 1950s until 1977, Burnham refused to accept the reality of the Sino-Soviet split, thinking it instead an elaborate ruse to fool the West into complacency. Burnham’s root error was that he had a childish view of communism as a monolithic global conspiracy. He was not capable of realizing (as figures like Kennan and Walter Lippmann did) that communist leaders were often guided by national interest more than ideology.

To be fair, Burnham was more moderate than most of his colleagues at National Review. Some at the magazine wanted to launch a pre-emptive nuclear war against the Soviet Union. “To stamp out world Communism I would be willing to destroy the entire universe, even to the furthest star,” L. Brent Bozell Jr., William F. Buckley’s brother-in-law, said. Burnham also wanted to launch a nuclear war, but in a more careful way and with no intent to destroy the whole of creation. As he wrote in National Review in 1958, “in bombing the bases opposite Quemoy, we can and should use tactical nuclear weapons.” In his 1964 book, Suicide of the West, he mocked liberals for their foolish worries about nuclear fallout.

Burnham was also a white supremacist. As Samuel Francis noted in the magazine Chronicles Magazine in 2002, “in the 1960’s, Burnham defended segregation on pragmatic and constitutional (though not explicitly racial) grounds and, by the 70’s, was suggesting actual racial separation of blacks in a ‘non-contiguous’ area accorded ‘limited sovereignty.’ He also defended both Rhodesia and South Africa, as well as other right-wing states.” In fact, Burnham thought that South Africa’s Apartheid system could be a model for America, with blacks confined to Bantustans.

Finally, any notion of Burnham as an advocate of “prudential” conservatism flounders on his history of political extremism. As in his Marxist years, Burnham was always torn between populist and patrician instincts. In The Machiavellians, Burnham warned that in the age of the Managerial Revolution there was a danger that executive power could be taken over by “bonapartist” leaders. Yet Burnham was often attracted to nationalist leaders who claimed to be tribunes of the people. After the Second World War, Burnham much admired Charles de Gaulle but came to turn against the French leader when De Gaulle accepted Algerian independence. After that, National Review’s sympathy turned to the French generals who tried to assassinate De Gaulle. Burnham was also a supporter of Joseph McCarthy, which cost him with his Cold War liberal allies: He was forced off the editorial board of Partisan Review in 1953 because he refused to condemn the demagogic senator from Wisconsin.

It’s true that one can find signs of some moderation in Burnham’s politics compared to the ravings of his National Review peers. Burnham preferred Dwight Eisenhower to Robert Taft, and Nelson Rockefeller to Barry Goldwater. He was quick to denounce Richard Nixon during Watergate, seeing the president as guilty of Caesarism. Still, these flickers of moderation hardly make up for a much more extensive history of extremism.

Moreover, there was an element of snobbery in these political choices: Rockefeller was an East Coast patrician and ardent supporter (like Eisenhower) of a foreign policy grounded in NATO, and so closer to Burnham’s ideal of elite leadership than hinterland figures like Taft and Goldwater. Perhaps because of his continued CIA connections, Burnham admired hawks of all sorts, including Democrats like Robert McNamara, whom Burnham praised in 1966 for bringing the Managerial Revolution to the Pentagon.

If you read them in a metaphorical way, the ideas promulgated in The Managerial Revolution and The Machiavellians do have some resonance in the age of Clinton versus Trump. Clinton’s data-driven campaign and policy wonkery makes her a kind of managerial hero whereas Trump embodies a Bonapartist reaction as a strongman who promises to take charge and unite the nation under his iron fist. This perhaps explains why Burnham is starting to find a new audience for the first time in decades. Still, even these ideas fall apart on closer inspection. The Managerial Revolution rests on the idea that the rise of a new technocratic class will displace capitalism, when the reality of the last few decades has been that capitalism has easily absorbed this new class. It’s still the people with money who call the shots, not their well-educated employees.

Any return to Burnham has to confront the fact that he’s not a thinker of great depth or lasting power. Instead of dusting off copies of The Managerial Revolution, conservatives like Continetti and Douthat would be well advised to look outside the National Review circle for guidance. There’s a range of rich mid-twentieth traditionalist thinkers who had no part of the conservative movement, and indeed are usually seen as Cold War liberals, but they have powerful conservative insights: figures like George Kennan, Walter Lippmann, Hannah Arendt, John Lukacs and Peter Viereck. Any conservatism that wants to be intellectually vigorous would do well to turn to such figures and give up on James Burnham.