First, remember: Nebraska is a place. It sits square as an anvil in the center of our maps, and yet, somehow, people on the coasts seem to forget it exists. Maybe that’s because Nebraska is also a land of ghosts, of small towns dwindling to the point where, in another generation, they might disappear altogether.

It wasn’t always so. The Homestead Act of 1862 brought more than a million people to the state—among them my ancestors, who farmed along the Platte River and opened general stores in Aurora, Murphy, and Giltner. But the act, which deeded 160 acres to anyone who would build a home and raise a crop, was no match for the drought of the 1890s and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. People fled in droves.

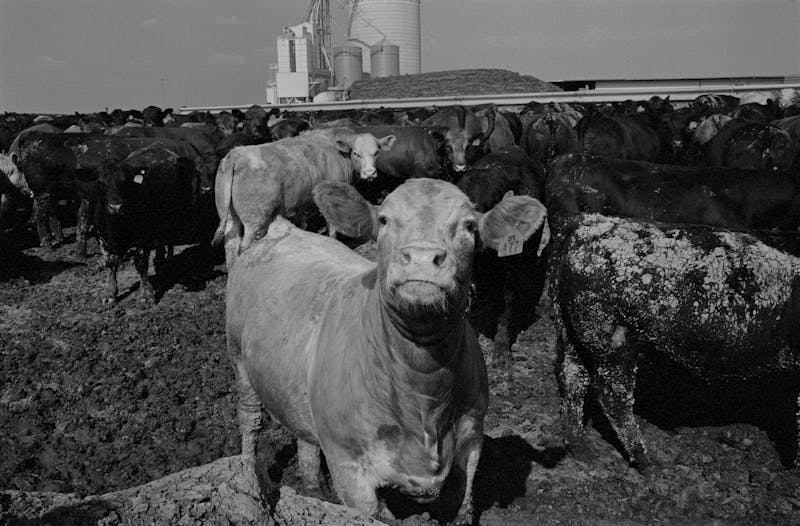

Technology, which promised to save small towns, only contributed to their demise. Combines, tractors, and trucks meant fewer men were needed to plant and harvest; hybrid crops, herbicides, and pesticides meant fewer hands were needed to tend rows in the summers. With each catastrophe—drought in the 1950s, the Farm Crisis of the 1980s—farms consolidated. “People used to have an 80-acre farm and raise a family,” a cousin of mine lamented. Now farms encompass thousands of acres and are often run by a single family.

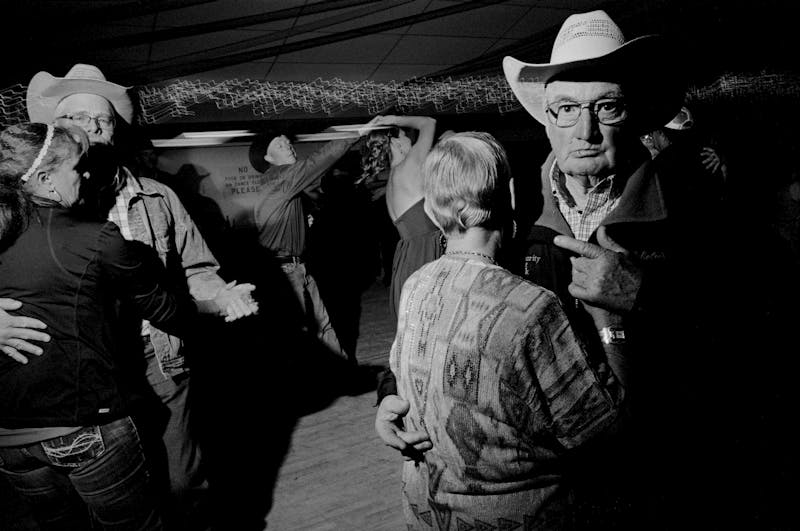

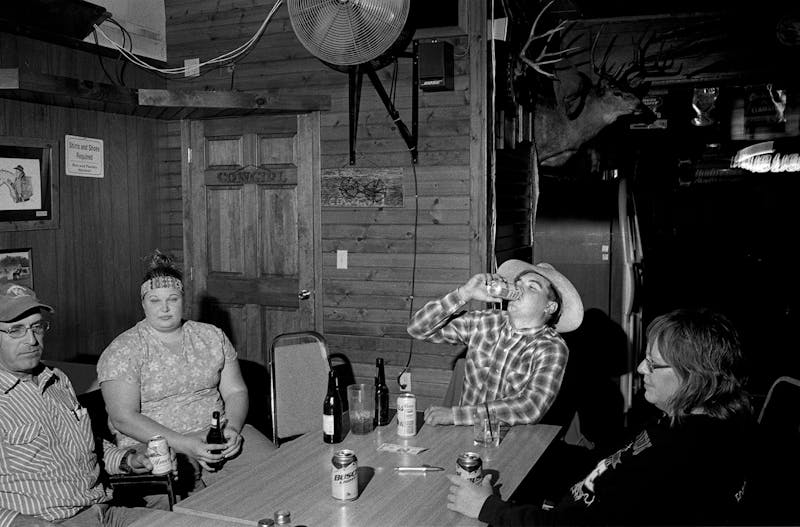

My father jokes that people in his hometown came to believe in a flat Earth: all their children left and never returned. Those who do stay, those documented by photographer Danny Wilcox Frazier, become landlocked castaways, marooned in crumbling farmhouses amid oceans of corn and soybeans. As tax revenues dwindle, rural communities struggle to provide adequate hospitals and schools. The worse things get, the more people go. And the more people go, the redder the state has become: Nebraska has not voted for a Democrat for president since LBJ.

Today, my father’s hometown is half the size it was when he was a kid. The restaurant where we’d go with my grandparents is boarded up. The shops are closed. The old movie theater is long gone. People feel abandoned and forgotten. There was a lot of talk during the past election about this demographic and the motives behind their voting. If you really want to understand, remember: Nebraska is a place, with people, not just precincts. Then ask yourself: If this were your home, how would you feel?

This photo essay was supported by a grant from the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund.