As Americans continue to reel from a seemingly endless succession of news stories about gun violence, the number of movies that examine these tragedies grows at a similar rate. Recent years have brought several notable documentaries: 3 1/2 Minutes, 10 Bullets, about the 2012 murder of Jordan Russell Davis; Newtown, about the after-effects of the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting; and Tower, about the 1966 shooting at the University of Texas. These films and others join the ranks of Michael Moore’s Oscar-winning 2002 film Bowling for Columbine as modern-day chronicles of our violent times.

But arguably the most despairing and bracing of this sad subgenre is the 1982 documentary The Killing of America, which cut together uncensored footage of death by firearms. (“This is a country that produces an attempted murder every three minutes,” warns the trailer.) Screened at just a few theaters on the east and west coasts, and reviewed by Janet Maslin in the New York Times as “exploitative and incoherent,” the film never received a proper U.S. theatrical release and has just this year been released for the first time on DVD domestically.

It’s not hard to understand why The Killing of America has been so

difficult to find: A grim, stark essay on this country’s penchant for violence,

the documentary combines archival footage of shootings from the 1960s to the

early 1980s—from the assassination of John F. Kennedy, to Charles Whitman’s University

of Texas sniper shooting, to John Hinkley’s attempt on Ronald Reagan’s life—as

well as interviews with serial killers and law enforcement, tied together with

a mournful narration by legendary voiceover artist Chuck Riley. It shares a

similar aesthetic to mondo

films—documentaries that offered

scandalous real-life images of shocking subject matter such as sex and

death—like 1978’s Faces of Death, which mixed fake and real

depictions of fatal encounters. But while The Killing of America is

more sobering than sensational, it has little in common with the solemnity of a documentary like Newtown. Decidedly

unoptimistic, The Killing of America doesn’t

leave the audience with a rousing call to action, or an uplifting end-credits

song. The best you’ll get is “Imagine” playing over footage from the public

memorial service after John Lennon’s 1980 killing, with a note that two people

were shot during the vigil. What’s remarkable about The Killing of America isn’t that it was forgotten—but rather how

the movie’s themes are still so relevant, like a news bulletin from the past.

The Killing of America was the product of three entrepreneurs: Mataichirô Yamamoto, a Japanese producer; Leonard Schrader, a writer and the older brother of Taxi Driver screenwriter Paul Schrader; and Sheldon Renan, a film archivist and author who, in the mid-1970s, was developing a screenplay about a hitman called Hollow Point for famed low-budget producer Roger Corman. In 1979, Leonard Schrader introduced Renan to Yamamoto. (Three years earlier, Renan and Schrader had met at a Brentwood party to celebrate Taxi Driver being green-lit.) Schrader and Yamamoto decided Renan was an ideal collaborator for The Killing of America because he’d done extensive research for Hollow Point’s screenplay by spending time with actual hitmen.

“That’s a scary thing to do, by the way,” says Renan, speaking from his office in Portland, Oregon. “[Hitmen] know that you know what they do. Bit by bit, you begin to pick up a sense of how hits occur—and how people kill each other, how professionals do it.”

Renan and Schrader shared a curiosity about violence’s hold on people. But when asked about his intentions for The Killing of America, Renan, who turned 75 this year, says simply, “We were just trying to make a commercial picture about something that bothered all of us.”

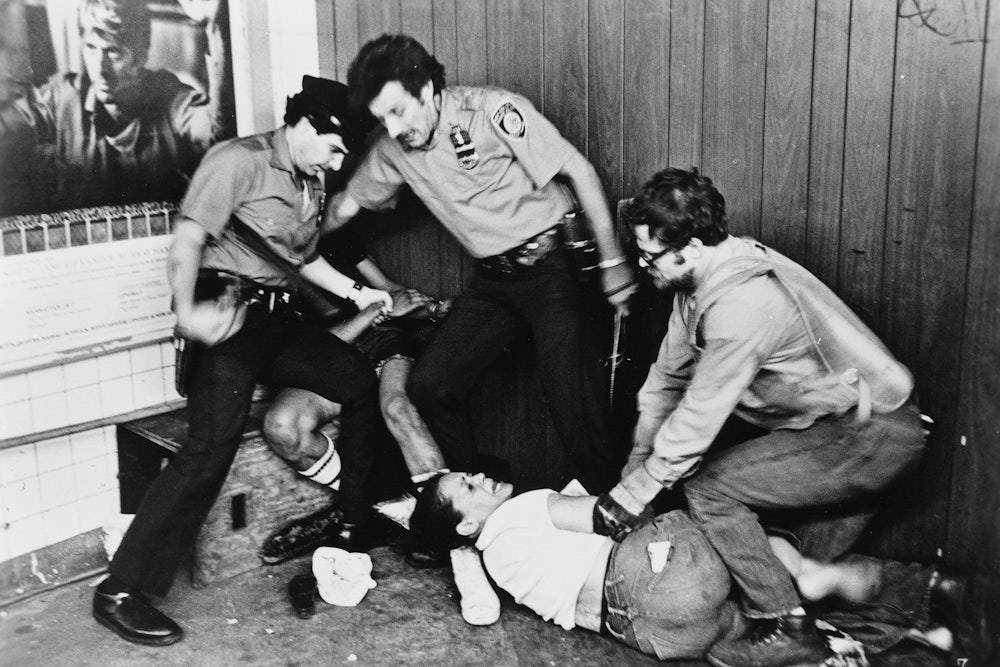

In 1980, Renan and Schrader began putting together the documentary in Los Angeles, Renan serving as director and Schrader writing the narration. They wanted to argue that President Kennedy’s 1963 assassination had unleashed something insidious within the country that had been festering since the postwar boom—the anger of the disenfranchised expressed through gunfire. Laying out statistics about Americans’ higher rates of gun ownership than any other country, as well as our elevated rates of homicides, The Killing of America offered no solutions to these problems, preferring to let an upsetting catalogue of facts wash over the viewer, punctuated by gruesome footage—including the autopsy of a murder victim and live news footage of an armed criminal being shot by San Diego policemen.

Since its release, The Killing of America has surfaced in different, condensed versions and Renan laments that his original cut, which he says featured more “elegiac” passages that helped break up the film’s darkness, has mostly been unseen in recent years. Even then, though, Renan admits that The Killing of America, in any incarnation, “is a little bit of a sledgehammer. [Schrader and Yamamoto] did not want me, in any way, to mediate or make it a do-gooder thing.”

After Faces of Death became a cult sensation in 1978, Yamamoto and the film’s backers wanted to do something comparably outrageous with The Killing of America. Renan and Schrader resisted. “Because Leonard was a more serious writer,” Renan says, “it came off in a more serious way.”

Renan does acknowledge they had essentially been asked to make a snuff film, “because it’s nothing but seeing people dying.” But unlike Faces of Death, there’s no lurid car-crash fascination in watching The Killing of America. In the 90-minute version I’ve seen, which is shorter than Renan’s preferred cut, the film forces viewers to spend some time retracing the lives of serial killers, rapists, and snipers who tore through two decades of American history, even sitting down for a one-on-one interview with the “co-ed killer” Edmund Kemper, who murdered his mother, grandparents, and at least eight young women in Santa Cruz, to discuss his crimes. But Renan and Schrader’s focus wasn’t on trashy titillation but, rather, erasing the line between these sociopaths and ourselves.

“He wanted to turn the audience into murderers,” Renan says of Schrader, who died in 2006 at the age of 62. “He wanted [viewers] to recognize that in themselves, ostensibly so that they would do something about it.” Later in our conversation, Renan makes the point another way: “Everybody thinks about killing people, in their mind. And everybody is guilty of all kinds of transgressions, in their mind.

But the chronicling of actual killing took its toll on the filmmakers. “A lot of the things that I did on this film seriously messed me up,” says Renan with a rueful chuckle, recalling his time going through the Los Angeles coroner’s office’s files, even observing autopsies. “It’s hard to explain,” he says of the experience of compiling the footage for the film. “It just really made part of you go dead. I basically had, like, PTSD.”

During the two years Renan and his team were putting together The Killing of America, new high-profile shootings would occasionally occur, including Lennon’s assassination and the attempt on Reagan’s life the following year. “It’s like, ‘You can’t keep up with it,’” Renan remembers thinking. “But it’s one of those things that tells you that you’re doing the right thing.”

Renan’s reaction to making The Killing of America was merely a precursor to the public response. When the film had its premiere at L.A.’s Nuart Theatre in 1981, Renan estimates that a third of the audience walked out. “They didn’t realize what kind of impact it was going to have,” he says, looking back at the screening. Even though plenty of the footage was already familiar to people by that time, like Zapruder’s capturing of JFK’s killing, “It hadn’t been put together [in that way].”

While the Public Theater in New York’s East Village screened the film every Sunday for about a year, The Killing of America quickly faded from view, its faint existence immortalized by Janet Maslin’s review:

The audience is treated to the spectacle of decomposing corpses being unearthed, and fresher ones being dissected in an autopsy room. There are still photographs of murder victims that leave nothing to the imagination—and there are plenty of things in The Killing of America that are even more obscene.

Although the film found an audience in Japan, The Killing of America was, according to Renan, something of an embarrassment to those involved with its making. “Most of us who worked on it didn’t advertise that we worked on it, because people didn’t like it,” he says. “There was such a reaction against it.” But to Maslin’s (and others’) contention that the film glamorized its murderers by giving notable killers like Sirhan Sirhan a platform, Renan disagrees, citing the experience he had as president for three years of a Zen meditation center. From that, he said, he learned “you just have to feel compassion for everybody—you just do. I do, anyway. For me, it was a journey into the depths to try to get some understanding.”

No wonder then that, underneath the paranoia and shock that reverberate through The Killing of America, there’s also curiosity, even sadness, about the unspoken connection between Americans’ thirst for violence and the easy availability of powerful weapons. “[Violence] is a discussion which is part of the American character—that’s how deep it is,” Renan says. “We have done terrible things in building this country, and then we paper over it. We don’t think about it. We don’t think about the violence that we ourselves experience and grow up in. We don’t think about the fact that at least one in every four women is raped. It’s just astounding what we don’t think about.”

Renan put the Killing of America experience behind him, eventually losing his only VHS copy of the movie, but the film itself didn’t vanish. Beyond its success in Japan, which Renan bases partly on that audience’s attraction to the movie’s gruesome spectacle, the documentary also began to develop a following in Australia—a country, it’s worth pointing out, that banned semiautomatic weapons in 1996, all but ending gun murders in that land. When Renan flew from Portland to Los Angeles to be interviewed for Electric Boogaloo, the 2014 documentary about Cannon Films, he discovered from the Australian crew that “It turns out that [The Killing of America] is this huge sleeper in Australia. Every college kid has seen it. Most dorm rooms have a copy.”

Now with its release on DVD and Blu-ray, a 35-year-old movie no longer seems dated or forgotten. From its footage of then-President Lyndon Johnson making an appeal for sensible gun legislation to the scenes of shattered onlookers reacting to mass shootings or tense hostage situations, The Killing of America feels like it could have been made yesterday—it’s only the names and the massacres that have changed.

Renan himself hadn’t seen the movie for years until he attended a recent screening. He was amazed how well The Killing of America held up. And he still believes the movie’s value is in its asking of questions and its insistence that we take a hard look at how we’ve come to accept violence in our culture. What once was disdained as a cheap exploitation film now feels terribly prescient, and startlingly vital and urgent. “Naiveté is a very poor strategy for survival,” Renan says about his film. “It’s better to know what things really are.”

Grierson & Leitch write about the movies regularly for the New Republic and host a podcast on film. Follow them on Twitter @griersonleitch or visit their site griersonleitch.com.