It was like a scene from Godard or Tarantino. A man splayed on his back on the polished floor of an art gallery, his scuffed soles facing the camera as if he had been flattened like the Wicked Witch of the East. Another man is in the foreground: black suit, black tie, the muzzle of a black gun pointed at the ground. His finger is aimed at the sky, and his face is contorted into a shout. Behind him are a row of pastoral images, tilted at such an angle that they appear to be running toward the ground.

It turned out that the dead man was the Russian ambassador to Turkey, his assassin an off-duty police officer apparently upset about Russia’s support of the Syrian regime’s assault on Aleppo. The ambassador, Andrey Karlov, was there to preside over the opening of an exhibition titled, “From Kaliningrad to Kamchatka, from the eyes of travelers.” The Associated Press photographer who captured his death also initially thought the incident was art. “[W]hen a man in a dark suit and tie pulled out a gun,” Burhan Ozbilici recounted, “I was stunned and thought it was a theatrical flourish.”

At this point, we are used to photos and videos that, at first glance, appear too fantastical to be real. Just last night, a truck plowed through a crowd of people in Berlin, the carnage captured by terrified civilians wielding smartphones. The line between the real and the phantasmagorical has never seemed thinner, a feeling that has only been accentuated by the election of Donald Trump, who, as far as viewers at home are concerned, may as well have exchanged the set of The Apprentice for the set of the White House.

It is no coincidence that Merriam-Webster announced yesterday that its word of the year was “surreal,” citing the fact that search traffic spiked for that word in response to four incidents in 2016: the terrorist attacks on Brussels, the coup attempt in Turkey, the bus attack in Nice (which turned out to be a foreshadowing of the truck attack in Berlin), and the election of Trump. It is a word that has its etymological roots in art, the surrealism movement of the early 1900s.

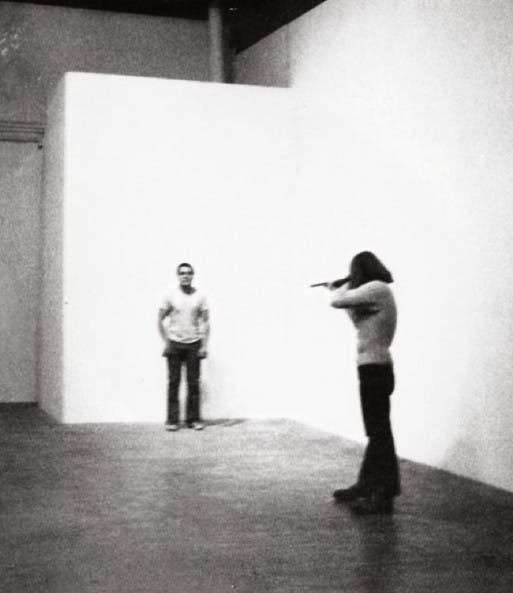

The assassination of Karlov was also reminiscent of a notorious piece of performance art in 1971 by the American artist Chris Burden. “Shoot” involved Burden being shot in the arm in an austere gallery in Santa Ana, California. It was done at fairly close range by a friend, who learned to be a marksman during the Vietnam War. “I didn’t relate to guns and I didn’t relate to shooting,” the shooter, Bruce Dunlap, told The New York Times last year. But he added, “I liked the challenge and the idea of shooting someone for art.” Burden himself said “Shoot” was “an attempt to control fate—or giving you the illusion that you can control fate.”

We can surmise that some similar idea drove Karlov’s killer, identified as Mevlut Mert Altintas, 22. The difference was that a sacred line was crossed, from concept to terrible reality, from life to death. While Burden’s project featured two men in exquisitely tense collaboration, Ozbilici’s photograph shows two dead men—one just doesn’t know it yet. Altintas would die shortly afterward in a shootout with police.

Burden once said art was “a free spot in society, where you can do anything.” As the critic Peter Schjeldahl noted in an essay on Burden, there was a limit to this radical idea, and that limit was death. Ozbilici’s photograph shows that it is the world itself that has become a free spot—where nothing is unimaginable and everything is unreal.