There was going to be a show about us. A show about people just like us, going through things just like the things we were going through! This was, at least, how I interpreted it, and how all of my millennial friends interpreted it, when Lena Dunham’s Girls premiered on HBO in early 2012. Dunham all but predicted this reaction in the show’s very first episode, when her character, Hannah Horvath, is suddenly cut off from her parents’ financial support at age 24, and is forced to find a job. She begs them to subsidize her a little longer. How else will she write her memoir? “I think I might be the voice of my generation,” Hannah pleads. “Or at least, a voice of a generation.”

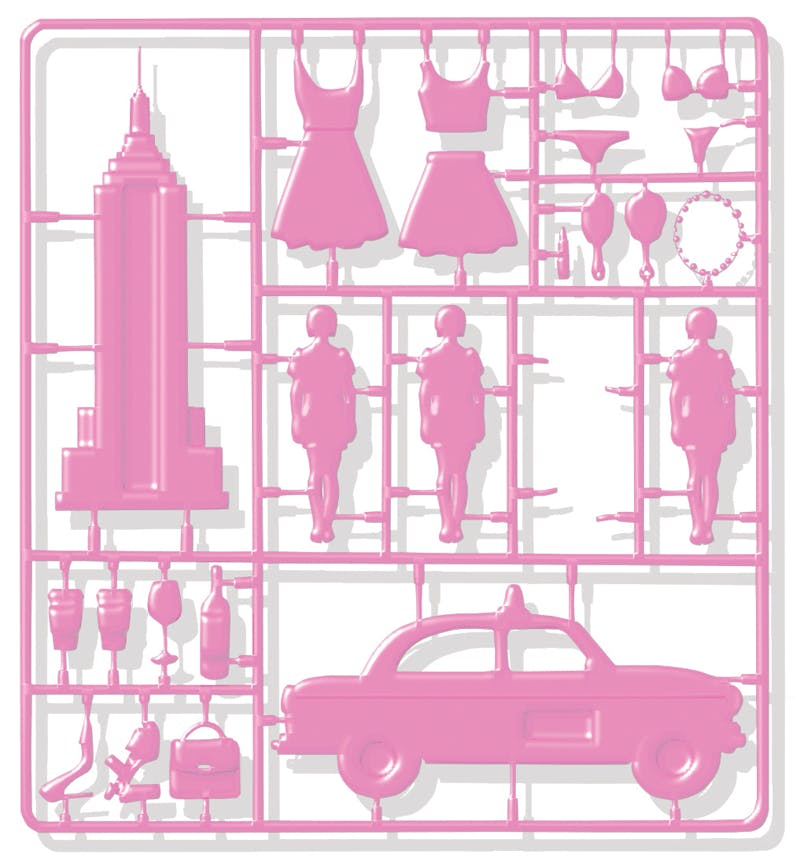

This was a promise that Girls—whose final season concludes in mid-April—could easily have made good on. And at first, it seemed to. The show’s first season took a familiar sitcom formula (four single friends, New York City), and gave it some shrewd updates. The pilot episode nodded to this, when Shoshanna attempts to describe Jessa using Sex and the City archetypes (“You’re definitely a Carrie, with like, some Samantha aspects, and Charlotte hair”). In Girls, Jessa was the free spirit; Marnie was the control freak; Shoshanna was the comic relief; and Hannah was—well, Hannah was Hannah. She never fell neatly into any category, and the show’s other characters soon followed her, moving out of their comfortable enclosures and into a space rarely depicted on television.

If Girls faced criticism as its seasons wore on, it was often because the characters were seen as too entitled, too selfish, too unlikeable to fit neatly into the tradition of shows about single girls in the city—a tradition, ultimately, of uplift. Even worse, Girls’ plot suggested something other than the characters’ inexorable development toward purpose, stability, and effortlessly fulfilling relationships. “You watch … examples of the zeitgeist-y, early-20s heroines of Girls engaging in, recoiling from, mulling, and mourning sex,” Frank Bruni wrote in The New York Times, “and you think: Gloria Steinem went to the barricades for this?”

Characters on Girls were—and still are—prone to becoming suddenly inscrutable in ways that hinted the writers didn’t quite confidently understand their inner workings. When, in season five, Jessa calls Hannah her “dearest friend,” you try to remember the last time they even shared a scene together, let alone whether they ever seemed truly close. Trying to make sense of the way Jessa suddenly falls for Hannah’s off-and-on-again guy, Adam, The A.V. Club’s Joshua Alston pondered the show’s apparently hidden dynamics: “Has [Jessa] felt this way about Adam all along? Is that why the friendship between Jessa and Hannah has always seemed to be more about shared history than shared lives?” From the end of the first season onward, it has been almost impossible to understand how the characters on Girls actually relate to each other, what their relationships are, or whether they even see themselves as sharing relationships anymore.

Girls wasn’t good at providing a whole generation with a simple, relatable set of stories, as Friends or Seinfeld had a generation before. For one thing, the concept for Girls sprang not from a focus group or a committee of producers, but from Lena Dunham, who wrote, acted, directed, and more. From the beginning, it was the TV show as auteur vision, in the tradition of Deadwood’s David Milch and The Wire’s David Simon and The Sopranos’ David Chase—all the Davids who made it OK to love TV. By now, it’s clear that Girls wasn’t about injecting female-driven sitcom with millennial relevance, but about redefining prestige television and the kinds of lives it can make us care about.

Early prestige dramas all greeted viewers with the same premise: Watch a man torn between good and bad. Watch a man who has lost his soul try to regain it. Watch a man sell his soul, and look for the moment when he passes the point of no return. The anti-heroes of shows like The Sopranos, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad obeyed no higher god than the accrual of power, and believed, either resolutely or unwillingly but always irreversibly, that life held no greater meaning. The first great prestige dramas were about frontiers and organized crime and corporate America, but they were also, above all else, about being a man, about men’s tortured relationships with masculinity. In contrast, the male characters on Girls—who have become more and more central to the series since its first season—often find themselves questioning the roles they have been handed, and learning that the only thing more frightening than failing to act like a man is seeing what you become when you do manage to act like one.

Even when showrunners started constructing prestige series around female leads, the masculinity paradigm still lingered. Showtime’s Nurse Jackie centered on a nurse hiding various parts of her life from everyone in it, wrestling with a pill addiction, and holding her ER together almost single-handedly. From the same network, Weeds featured a suburban mother who turns to pot dealing to keep her family afloat after her husband’s sudden death. Prestige TV was stuck with a clear template: Focus on one person with a lot of secrets, and explore the ways their transgressions also make them feel more powerful and alive than ever before. Girls helped to break open that paradigm for good.

Girls was addicted not to secrecy but to openness—or “overshare.” And rather than focus on one clear, troubled protagonist, Girls centered on something more lifelike: four young women who live in relatively tight formation, then gradually drift apart, their lives spiraling outward as the seasons progress. At various points, Hannah moves to Iowa to start an MFA, Shoshanna heads to Japan for work, Jessa checks into rehab, and Marnie tries to lose herself in marriage. Although they each come back, the series no longer depicts an unshakable quartet, but the random, tenuous sorts of ties that connect us in reality. It shows not the community we sometimes wish ourselves a part of (the TV version of community, where everyone is always the same forever), but community as we actually experience it.

This central breakthrough of Girls has rippled through the best new television, from Insecure to Broad City to Divorce to High Maintenance. The act of simply depicting an unresolvable fight between friends, or a realistically awkward sex scene, has grown infinitely easier since the show premiered five years ago. Girls validated a strikingly new idea in television: that people want to watch people whose lives are just as confusing and nonlinear as their own.

We’re trained to approach the prestige drama as if we’re reading a novel: Character growth is supposed to be visible and ongoing; characters’ stories remain reliably interdependent; we can trust that we will always witness the crucial moments in a love affair, a tragedy, a dream won or lost. But from its first season, Girls presented some of its most arresting storytelling by emulating not the novel, but the short story. Each season has contained at least one episode that focused on just one or two characters, separating them from the rest of the group, often revealing more about a character’s emotional state than the rest of the season’s episodes combined.

The series first took this approach with season one’s “The Return,” in which Hannah visits her parents in Michigan. For a moment, the rest of the characters, and their world, disappear. Hannah’s posing and wit have kept her afloat in New York, but now she is suddenly, newly vulnerable. As we watch her struggling through conversation with an old high school classmate, and phoning her sort-of boyfriend, we see a new side of her character: the confused and startlingly resilient lost girl we will soon follow into far more complex territory, even—especially—when she has no idea where she’s going.

Taken as stand-alones, these single-character episodes have the precise, sure-handed power not of a great novel, but of a gemlike short story. They are by definition slight. They don’t strive for the epic; they don’t even necessarily depict their characters gaining wisdom they will take back to the main story line. A character doesn’t have to be enacting a clearly delineated portion of their arc—here is where I become callous, here is where I become empowered, here is where I become myself—to be worthy of attention. Girls insists that even the most halting kind of progress is worth trying to understand—and, in fact, it may be the only kind of progress that exists.

“I’m not here to change you,” Marnie tells her ex-boyfriend in “The Panic in Central Park,” a fifth-season short-story episode that belongs entirely to her. “I don’t need to change anybody anymore.” We don’t know how Marnie got here, or why this is the moment when her need for control finally breaks. But by now, we’ve spent five years watching her trying again and again to arrange her life into the shape she wants, only to realize—again and again—that what she thought she wanted is suffocating her. Marnie’s growth seems to come not through any newly philosophical approach to life, but from the desperate knowledge that she has to reject the way she’s lived so far, even if she isn’t sure what to reach for. Growth, in this episode, and in so many others, is ugly and sudden. It doesn’t leave us with much dignity. But don’t worry, Girls says: Nor does anything else.

By refusing to speak for a generation, Girls has done exactly that. Being a millennial is nothing more or less than coming of age in a world that can no longer offer easily-won jobs or clear-cut career paths or well-defined family roles—the plots that previous generations could be forgiven for confusing with reality. By depicting characters deep in the work of jettisoning the narratives they have done their best to live by, Girls is telling the only story that can be told about a generation in search of one.