Last Thursday afternoon, in a ballroom at the luxurious Mandarin Oriental hotel near the National Mall, President Donald Trump’s 31-year-old senior advisor Stephen Miller concluded a panel discussion on “Economics in an Age of Populism” with a matter-of-fact prediction about a new world order. “The protests and the unrest and the rebellion you’ve seen in the American voter is not a small event or a passing event,” he told the crowd of conservatives. “It is a profound, total, and complete repudiation of elite governance at every level.... It is colossal in its scope and reach. We are only seeing the very beginnings of it, and the world is going to change in irreparable ways.”

“If it goes according to the values we discussed today,” he added, “it will be an extraordinary win and victory for everyday working people all across the country.”

These aren’t the values of the conservative establishment in Washington—or at least they weren’t. Before Trump, elite conservatives generally weren’t populist. They didn’t support trade protectionism or erecting border walls or dispatching deportation forces. For all their talk of security and law enforcement, Republicans retained a commitment to relatively liberal immigration policies. They even talked periodically about comprehensive immigration reform, including citizenship or “earned legal status” for undocumented people. The organizing principle of conservatism was, ostensibly, limited government.

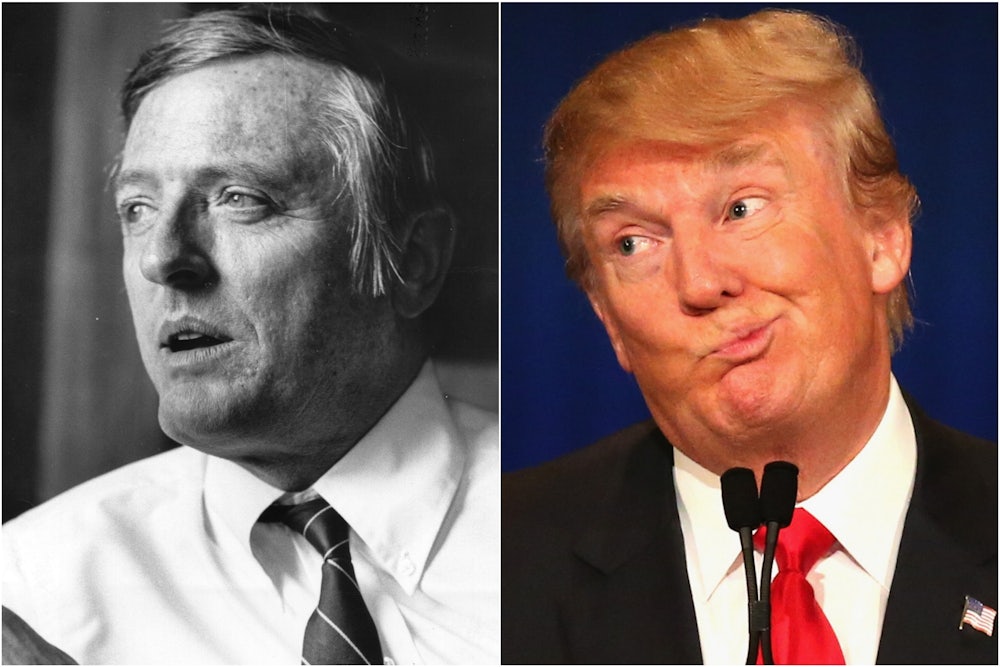

Now that Donald Trump is president, though, he and his team are attempting to win over traditional conservatives—like those in the Mandarin Oriental audience last week. Miller was speaking at the annual Ideas Summit hosted by National Review, the pioneering conservative magazine founded by William F. Buckley to “stand athwart history, yelling Stop.” In that tradition, National Review published an entire issue early last year, titled “Against Trump,” about why he was “a menace to American conservatism who would take the work of generations and trample it underfoot,” in the words of the magazine’s editors.

But after Trump won the Republican nomination, National Review dedicated itself more to criticizing Hillary Clinton than stopping her opponent. And after Trump won the election and took office, it became a leader of the “anti-anti-Trump” movement, attacking Trump’s critics even while disagreeing with the substance or execution of his actions. The magazine also began to focus on the many areas where it agreed with him.

“We’re transactional on Trump,” National Review’s top editor, Rich Lowry, told me. “We want to encourage him and praise him when he’s right and try to correct him and push him in a different direction when he’s wrong. The hope is that you would get a consensus in the party that economics needs to be more populist but at the same time we’re not throwing out the baby with the bathwater and totally overthrowing Reaganism. At times that’s the sound you get from people in the Trump administration.”

Lowry’s commitment to Reaganism notwithstanding, National Review’s new tack on Trump has many wondering if the magazine has lost its way: whether a publication that has long been a stalwart defender of principled conservatism has become just another partisan organ. Is National Review sacrificing its values in a desperate bid for relevancy under a president it vehemently opposed? Or is such ideological flexibility the only reasonable path for a traditionally conservative publication in the age of Trump? Perhaps it’s neither—that Trump, rather, is changing the very nature of conservatism in America, and thereby changing the very nature of National Review.

National Review certainly has a tradition of standing for principle over partisanship. Buckley famously took on the conspiratorial anti-communists of the far-right John Birch Society during the 1960s. “By 1961,” John B. Judis wrote in William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives, “Buckley was beginning to worry that with the John Birch Society growing so rapidly, the right-wing upsurge in the country would take an ugly, even Fascist turn rather than leading toward the kind of conservatism National Review had promoted.”

But as the New Republic’s Jeet Heer noted earlier this year, the magazine’s conservatism was ultimately compromised by—or, more favorably, adapted to—its ascendance in the Republican Party:

The magazine was born in 1955 as a revolt against the moderate Republicanism of Dwight Eisenhower. When the conservative movement inspired by National Review took over the GOP, the magazine became intimately linked with the party, and started having trouble criticizing Republican administrations. As John Judis showed in his biography of William F. Buckley, the National Review founder began to forgive conservative politicians like Ronald Reagan who strayed from right-wing orthodoxy in order to win elections. The balancing act Buckley learned to perform, of being both a supporter of the party and a keeper of ideological purity, tilted increasingly in the direction of partisanship.

The “Against Trump” issue in January 2016 seemed like another John Birch Society moment for National Review. It assailed his character and temperament. It warned against his “free-floating populism with strong-man overtones.” Trump took notice:

National Review is a failing publication that has lost it's way. It's circulation is way down w its influence being at an all time low. Sad!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 22, 2016

Very few people read the National Review because it only knows how to criticize, but not how to lead.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 22, 2016

The late, great, William F. Buckley would be ashamed of what had happened to his prize, the dying National Review!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 22, 2016

Many National Review staffers joined the Never Trump movement, pledging not to vote for him against Clinton. Senior editor Jonah Goldberg even praised Clinton for condemning the pro-Trump “alt-right” while his fellow conservatives didn’t. His piece was titled “Time to John Birch the Alt-Right.”

But now, critics charge, the magazine is drifting toward partisanship again. In January, Heer wrote that National Review “is starting to embrace, slowly and awkwardly, the Republican president out of fealty to the party.” The Atlantic’s Peter Beinart devoted the bulk of his piece on “The Anti-Anti-Trump Right” to what he sees as National Review’s technique: “Step number one: Accuse Trump’s opponents of hyperbole.... Step number two: Briefly acknowledge Trump’s flaws while insisting they’re being massively exaggerated.” Beinart wrote that this approach “minimizes Trump’s misdeeds without appearing to defend them.” As one journalist at a rival conservative publication told me, the magazine’s qualified praise of Trump now “seems rather disingenuous after they were so hysterical about him during the primaries.”

But National Review defends its approach. “I think there are points of contact between a sober nationalism and an enlightened conservatism,” Ramesh Ponnuru, a senior editor at the magazine, told me while sipping a glass of white wine at a reception after Miller’s panel. “Rich Lowry and I wrote an article about why nationalism rightly understood is an important component of conservatism. I think it’s important to sift and try to identify what’s reasonable and constructive and what needs to be corrected.”

Lowry said that Trump has moved in a more conventionally conservative direction since the primaries, when the candidate “was making more of a big deal about price controls for the pharmaceutical companies.” Lowry called Trump’s cabinet picks “superb” and Neil Gorsuch’s nomination to the Supreme Court “a home run.” At National Review, he said, “We generally support what he’s doing on immigration in terms of more enforcement.”

Meanwhile, Trump seems to have put on hold the issues where the magazine has its strongest disagreements with him, including trade and infrastructure. “I think sometimes liberals seem to think we should be in the same place they are on Trump,” Lowry said. “We share concerns about his character and his temperament. Those are enduring concerns that aren’t going to go away. But where we’re different is we want 70 percent of this stuff to happen.”

Staff writer David French, who was a prominent Never Trumper and even mulled a third-party challenge to Trump in last year’s election, told me the early days of the administration have been like watching a ping pong match. “You’re going, ‘Right. Wrong. Yes. No,’” he said. Like Lowry, French praised the president’s cabinet. He also said he supports Trump’s approach to terrorism and shrinking government bureaucracy. “I agree with the priority articulated to dismantle the administrative state,” he said, echoing a stated goal of Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon.

Ponnuru was less sanguine. “The people on the right who say he’s doing a great job are grading him on a curve and placing a lot of weight on media controversies in which they take his side and not much weight on the actual policy change that has occurred so far in this administration,” he said. “It is true that these are early days. It is also true that both George W. Bush and Barack Obama were further along than he is now and I think he’s had a slow start that is deeply connected to the flaws a lot of us saw in him during the campaign—the fact that he has no interest in public policy, that he didn’t campaign on a real agenda and he’s therefore been unable to generate consensus in the party.”

Ponnuru, who, like French, voted for the independent conservative candidate Evan McMullin last fall, criticized Trump for failing to stay on message and being slow to fill key administration post. “There’s a running theme of concern about him as potential strongman,” Ponnuru said, “but in a lot of ways he’s a weak president.”

With regard to the “anti-anti-Trump” knock against National Review, Ponnuru allowed that Beinart “was on to something in his Atlantic criticism of conservatism generally.” “It is certainly the case that, given that we have a Trump presidency, we would like to make the best of it,” he said of National Review. But Ponnuru said some of their criticism of Trump’s opposition is warranted. “The ‘anti-anti-Trump’ tendency is an important tendency in conservative opinion right now, and it’s reflected in what we write,” he said. “A lot of the anti-Trump stuff does seem wrongheaded and foolish to me, and I make no apologies for criticizing it.”

The challenge is to ensure it doesn’t go too far.

“I do think the temptation, the danger, is that you’re not putting enough attention on mistakes or foolish things, wrongheaded things, that the administration is doing, if you only do that,” Ponnuru said. “That’s something that individual conservatives have to navigate as well as collectivities of conservatives. I’m not going to name names, but there are people we publish and people other people publish who I think have tipped over too far in one direction or another.”

French said he’s also conscious that the “anti-anti-Trump” approach can be a dereliction of duty. “I think that if somebody has become exclusively ‘anti-anti-Trump’ it’s kind of a way of making—I don’t want to impugn motives—but if you’re against Trump, one way to sort of live at peace in this world now within the conservative movement is to be exclusively or dominantly ‘anti-anti-Trump,’” he said. “You can look at things that are legitimately overreach in my view—legitimately hysterical and wrong in my view—and talk about that all day long.”

Assessing how much to police Trump versus his critics isn’t the only challenge for National Review. Lowry said Trump’s rise has forced the magazine to consider ideas and policies it would have previously dismissed, particularly on trade. “We take Trumpism as an opportunity to widen our ideological aperture,” he said. “We’ve run pieces on trade that we probably wouldn’t have run prior to the advent of Trump. I don’t think we’re wrong on trade. I think maybe conservatives were a little too facile on trade. It’s kind of pointless to have this guy elected president and not at least ask those kind of questions.”

National Review started wrestling with how to make conservatism work better for workers after Mitt Romney’s infamous “47 percent” comment in 2012, according to Lowry. “There are some people who tried to defend it or even said they agreed with it and it was a wonderful thing,” he said. “We were never with them. We were saying clearly after 2012 that the party needed to talk more about workers and less about entrepreneurs. We wanted the party to move in a more populist direction, but not as far as perhaps Trump is taking it and not with the vehicle of someone like Trump. He managed to pull this off in part because the consensus within the party was so brittle and out of date.”

Even now, as Trump supports a House Republican healthcare bill that would hurt the working class, Lowry said he’s not comfortable with the current Republican position. “My basic take is I wish [House Speaker] Paul Ryan were more populist, and I wish Trump were more conservative,” he said.

As a business proposition, National Review is increasingly competing with outlets offering overt support for the White House. Publications like American Greatness and American Affairs, which are trying to intellectualize Trumpism, could conceivably present a commercial challenge down the line. French questioned the premise of these publications, saying, “I’ve always taken exception to the idea that Trump has a core political philosophy.” But Lowry said he welcomed their contributions: “I think having some publications trying to put some more intellectual meat on the bones is a good thing. I do think it’s a distinct worldview and it’s one that hasn’t had much intellectual expression or defense.”

National Review insists it won’t defend Trump unless it’s warranted. On questions of character, in particular, French said conservatives have a duty to speak up against him. “I don’t think you can divorce character and policy,” he said. “I was very dismissive of the Democratic argument in the Clinton era in the late 1990s that all this could be compartmentalized—‘Look, let’s just focus on what Bill Clinton’s doing well, wall off the things he does badly, and defend him against all Republican comers.’ There were an awful lot of us—and I’m a conservative Christian—who were saying no, no, no, no. There’s a lot that matters here beyond mere policy. There’s national character. There’s culture. There’s morality. All of those things matter a great deal.... I found it very distressing when I heard in this election cycle, coming back at me, a lot of arguments from Republicans that I heard from Democrats in the 1990s.”

Lowry said Trump’s character flaws could hurt his presidency. “It’s an office where usually, if you have any character flaws, the pressures of the office expose them,” he said. “Certainly he’s publicly advertised his character flaws more than any other president in the history of the country, I don’t know, since Andrew Johnson showed up drunk to Lincoln’s inauguration or something. The question is whether he can control it enough to succeed.”

Call it partisanship. Or call it pragmatism. But National Review clearly does want Trump to succeed, and will attempt to steer him—if he’s even listening. “We hope he’s the best Donald Trump he can be,” Lowry said. And so Buckley’s successors stand athwart history again, murmuring Proceed with Caution.