In the early morning of March 9, 1973, Robert Hoyt, a 24-year-old black motorist, rear-ended a white man named Raymond Peterson on Detroit’s westbound Fisher Freeway. Hoyt, who worked the late shift at an auto factory, had apparently dozed off at the wheel.

Peterson, however, interpreted the collision as a deliberate act of aggression. He was an undercover police officer, driving home in an unmarked sedan. His partner, Gary Prochorow, witnessed the accident. He happened to be driving in the same direction in his own car, also unmarked. The two officers had just stopped at a diner for coffee after an uneventful night’s patrol.

Prochorow also assumed the collision had been intentional. After shouting from his window for Hoyt to pull over, he fired a shot from his moving vehicle, striking Hoyt in the wrist. Panicked, Hoyt exited the freeway, both officers in pursuit. Just past the exit ramp, he finally had no choice but to stop. When Peterson emerged from his vehicle, he thought he saw Hoyt reaching under his seat for a gun. “My reaction was instinctive, sharp like a scalpel,” Peterson later recalled. “Boom. He went down.”

In fact, Hoyt was unarmed. So, after an unfruitful tossing of Hoyt’s car, Peterson covered his tracks: He pulled out a six-inch knife, slashed his own coat, wiped the knife’s handle clean of prints, and dropped it on the ground beside the crime scene. Hoyt, shot in the abdomen, was later pronounced dead on arrival at Detroit Receiving Hospital.

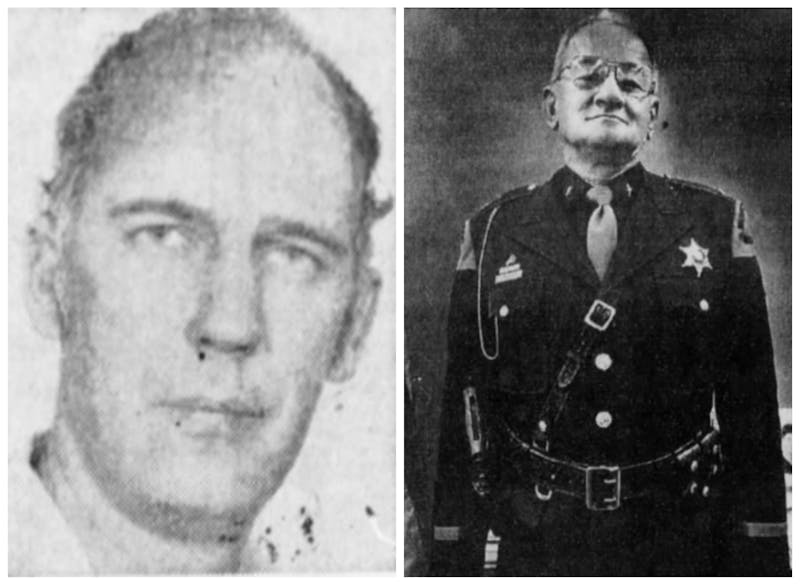

Peterson had already achieved a certain notoriety in Detroit. A 1971 profile in the Detroit Free Press described him as looking “more like a radical college professor or folk singer than what he actually is—a Detroit police man who has probably been part of more violence in recent months than any other cop in the country.” Hoyt marked the tenth shooting death at which Peterson was present over a two-year period. He’d personally killed six men, all black, many unarmed, and wounded five others.

Peterson joined the Detroit Police Department in 1961, at age 25. During his first decade on the force, according to official records, he was responsible for only six injuries, and received 41 citations and commendations for meritorious service. Then, in January 1971, Peterson was recruited to join an elite, highly secretive unit within the police department. The new unit was created to combat street crime, but it soon became infamous in Detroit’s black community as something closer to an execution squad. Though the initiative’s official designation was predictably anodyne and bureaucratic—“Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets”—the unit quickly became known by its more descriptive acronym, STRESS. It would prove to be one of the most excessive and lawless policing experiments in modern history.

As word of his body count spread, Peterson was vilified by black citizens and cheered by his fellow cops. Both sides adopted the same nickname for him. They called him Mr. STRESS.

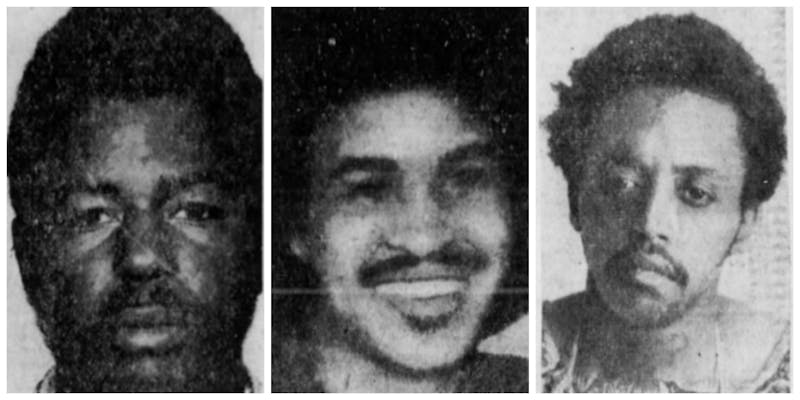

At the precise moment the most notorious killer cop in Detroit was planting a knife on a man he’d just murdered, the city’s most notorious cop killer sat in a jail cell just a few miles away. Hayward Brown was 18, black, a lifelong Detroiter, arrested numerous times as a juvenile. His father worked on the line at Ford’s River Rouge plant and his mother was a homemaker.

Two months earlier, police claimed, Brown and an accomplice had attempted to rob a bank on Woodward Avenue, Detroit’s main thoroughfare. To create a distraction, they had tossed a pair of Molotov cocktails into the lobby of a Planned Parenthood clinic above the bank. In the pandemonium that followed, they were forced to flee. Brown’s accomplice tried to hail a taxi on Woodward, but wound up escaping on foot. Brown, dressed in a long coat and floppy hat, crossed into the Cass Corridor, a rough neighborhood surrounding Wayne State University.

Newspaper accounts described the wild, extended pursuit that ensued as a “movie chase,” like something out of the recent Best Picture–winner, The French Connection. When a pair of Wayne State security guards approached Brown as he fled, he calmly pulled out a revolver and fired three shots through their windshield. One of the guards gave chase on foot and was fired on twice more. Another security guard caught up with Brown several blocks away; Brown shot at him as well, then dashed into a burned-out storefront. While he was cutting through a residential yard, a German shepherd bit him on the seat of his pants. Finally, on Trumbull Avenue, several Detroit police officers tackled Brown to the sidewalk and placed him in custody.

In the squad car on the way to the police station, Brown confessed to the firebombing. But in arrest photos released the following day, Brown’s face appeared bruised, and a doctor who examined him suggested that he had been “badly beaten,” noting multiple abrasions and contusions on his face, chest, and hands. The police claimed Brown had injured himself while unsuccessfully attempting to hop a fence.

There were plenty of reasons to doubt the official narrative. Before his arrest, Brown had been on the lam for nearly two months, the lead suspect in a pair of dramatic shoot-outs—one outside of the known residence of a major heroin dealer—that had left one police officer dead and five others wounded. In a press conference, Detroit’s chief of police had dubbed Brown and his two alleged accomplices “mad dog killers.” What followed was the largest manhunt in Detroit history, with the police effectively putting black neighborhoods under martial law. One of the officers who arrested Brown had been carrying his photograph on a clipboard in his squad car.

The case had another significant, and complicating, detail: All of the police officers who had been shot were members of STRESS. Brown’s brilliant, flamboyant attorney, Kenneth Cockrel, seized on that fact to fashion a defense for his client. Perhaps the most famous black radical in Detroit at the time—picture Johnnie Cochran as a committed Marxist—Cockrel was eager to put the police department in general, and STRESS in particular, on trial. Shortly after accepting Brown as a client, he offered a surprising, galvanic twist: Brown, he argued, was no drug dealer. He was actually a revolutionary-minded vigilante inspired by the Black Panthers who was dedicated to driving the dope dealers from his neighborhood by ripping off their stashes and threatening them with violence.

Like Raymond Peterson, Hayward Brown became a polarizing figure in Detroit, only their constituencies were flipped: A “mad dog killer” to police, Brown would be venerated as a folk hero by the police’s victims. “Our position is that Hayward Brown is not a client,” Cockrel said. “He is a comrade.” At a press conference held at the Wayne County jail, Brown “appeared calm and confident as he spoke,” according to the Free Press. He informed reporters that “the community was being drowned by drugs, and the authorized parties ... weren’t doing anything. We took it upon ourselves to do something.” Entering the courtroom for the first time, he looked at the cameras and raised his fist in a black power salute.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the 1967 Detroit riot, the second-largest civil disturbance in modern U.S. history. The inciting incident, a police raid on a black speakeasy, and the government response, a mobilization of both the National Guard and the U.S. Army, set the tone for the ensuing decades. To many Americans, Detroit became synonymous with violent crime and economic decline. To many black Detroiters, meanwhile, local law enforcement became a hostile occupying force.

In the late 1960s, Detroit was still majority white. Two years after the riot, a conservative prosecutor and former sheriff named Roman Gribbs was elected mayor, in part by running on a Nixonian “law and order” platform. To serve as police commissioner, Gribbs appointed John Nichols, a native Detroiter who started out as a beat cop. A taciturn workaholic, Nichols had seen combat during World War II, kept his hair in a tight crew cut, and answered to the nickname “Uncle John.” He’d also built up a degree of comity with the black community. Civil rights leaders “regard him as progressive,” the Free Press noted after his appointment.

Nichols faced a daunting task. Robberies in the city had risen 67 percent in the previous two years. A staggering number of them—some 18,000 in 1970—took place on the street, and 85 resulted in murder. In one of his first orders of business, Nichols instructed his staff to conduct a thorough study of the available data and build a detailed profile of the “typical robbery.” They found that victims were most often “male, not young, nonwhite, and living in or near the neighborhood in which the robbery took place,” while criminals tended to be “young, nonwhite, and armed.” One of the most salient factors, for Nichols, involved the sheer brazenness of the crimes. As he later testified at a congressional hearing on street crime and policing:

In contrast to what one would believe, most robberies were not being carried out covertly. They occurred openly and in full view of other citizens and potential witnesses on the street. It was apparent that the criminal felt safe in carrying out his act in front of others. He obviously believed that large segments of the community were either so apathetic or intimidated that they would not interfere. His only concern then was to assure himself that there were no police in the area.... In retrospect, the answer seems too obvious: a zero visibility patrol.

And so STRESS was born. With the help of computer data, Nichols planned to flood the streets with undercover cops disguised as drunks and priests, hippies and elderly women. When robbers tried to hold up these “decoys,” backup officers would swoop in and make an arrest. As Nichols explained to the congressional committee, his department hoped to “perfectly blend men into the environment” on a scale never before attempted. “With STRESS,” he testified, “the criminal must fear the potential victim.”

Plans for STRESS coalesced in the winter of 1970. Out of a department of 5,000, only some 80 officers were recruited to join the clandestine unit. When Raymond Peterson was approached by his superiors, he found the invitation flattering. “What the hell?” he recalled thinking. “Variety is the spice of life.”

STRESS instructed plainclothes officers to blend in everywhere: at the downtown “ethnic” festivals (Polish, Irish, Arab, Italian) that took place on summer weekends; outside of auto factories as workers streamed into the streets and parking lots during shift changes; in the rail yards where thieves boosted tires from freight cars. But the most controversial aspect of the unit was the decoy squads. Each night, after their commanding officers consulted a large map pinpointing the previous day’s street crimes, the new STRESS recruits fanned out across the city, usually in teams of four. An undercover “point man,” disguised as an easy victim, took the lead, tailed by an undercover back-up and two more “cover” officers surveilling from a distance. The neighborhoods targeted for decoy patrols were generally “heavily populated with pensioners, alcoholics, homosexuals, prostitutes and their clients,” but also racially diverse enough to allow the members of the nearly all-white STRESS unit to walk the streets without standing out.

The existence of the unit was revealed in a flippant 1971 Detroit News article. “Muggers beware!!” the story began. “That helpless looking little old lady you are about to rob may be a wiry, young cop, whose shawl conceals a loaded .38.” Describing a “hush-hush project designed to make Detroit streets safer,” the article revealed that undercover cops would “pose as average people on the street”—grocery clerks, gas station attendants, cab drivers. “They will be prime bait for robbers who prey on such people,” the paper reported. “And they will be armed and ready.”

But in truth, for all the careful planning, STRESS at first seemed like a bust. “We weren’t getting any results at all,” Peterson later recalled. Would-be robbers saw right through the disguises. “We walked our asses off. But I guess we were too obvious. Too uptight.”

Eventually, Peterson said, the officers got their “act polished” and “started to get hit on.” On the first night he was robbed, May 3, 1971, Peterson had costumed himself as “a white guy down a little on his luck.” Sometime around midnight, at the corner of Woodward and Peterboro, a black man named Dallas Collins stole up behind Peterson. With his hand in his left pocket, Collins jabbed a finger into Peterson’s back. “Give me your wallet, motherfucker,” he commanded. Reaching into Peterson’s hip pocket, he discovered a billfold, grabbed it, and began running. Peterson drew his own (real) gun and ordered Collins to halt. Then he fired as many as four times, striking him once in the arm.

Collins, lurching and holding his shoulder, disappeared into an alley. Moments later, Peterson and one of his partners, Marvin Johnson, found him hiding in a building. According to Peterson, Collins made a move for Johnson’s gun. “Without thinking, I automatically squeezed off another round and hit him in the chest,” Peterson said. “He went down.”

Afterwards, Peterson recalled what he was thinking: “I expect to see my family again at all costs, and it’s better him than me.” He added, “They found my wallet in an alley somewhere. Fortunately, the guy didn’t die.”

One week later, the Free Press noted, Peterson would kill a man 100 feet from the same alley.

Years after his arrest, Hayward Brown told a reporter that he “used to be a St. George. You know, fighting those dragons. I was a chaser of causes. I was for the underdog. I was aware something was wrong, but I didn’t know what.” One of his attorneys, Chokwe Lumumba, a black nationalist who was later elected mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, recalled Brown was “pretty politically aware, as any young black man coming up in the late ’60s and early ’70s had to be. But he was clearly a street brother rather than a member of the active intelligentsia.”

Brown “probably had a genius IQ,” recalls his first cousin, the poet and historian Melba Boyd, a distinguished professor of African American studies at Wayne State University. Brown didn’t like school, Boyd says, and “got in a lot of mischief, doing petty stuff, driving his mama crazy.” But he also read constantly—James Baldwin, Malcolm X, American history, poetry—and had the mild-mannered, upbeat personality of someone “blessed with good looks and charm.”

Police would later cite Brown’s 14 juvenile arrests, along with two busts for armed robbery and carrying a concealed weapon just after his eighteenth birthday, as evidence that he was a “dope addict,” as “high-placed sources” described him in the newspapers. Boyd calls the charge “ridiculous.” At trial, Brown insisted he’d only snorted heroin “for about a month” in 1970. He found Malcolm’s militant anti-drug message inspirational; he had seen friends murdered by drug pushers, he later said, and he saw them as a scourge to be eradicated. He also admitted to supporting himself by robbing johns who came into the neighborhood looking for prostitutes.

Brown found kindred spirits in two students at Wayne State University: his cousin John Boyd, and Boyd’s friend and classmate Mark Bethune. Boyd had recently returned from Vietnam, and was struck by how much his hometown resembled a war zone. “He looked around and felt like the community was under siege, not just by the police but by the heroin plague,” recalls his sister, Melba. “We thought of it as a form of germ warfare. And the police weren’t really doing anything about it.” People in the community used to refer to the Tenth Precinct as “the drug house,” because so many of the cops there were rumored to be accepting kickbacks from the dealers.

Bethune, the youngest of eleven children, had moved into a YMCA when he was 14, later joining the Black Panthers. His nickname was Igbo, “after the African tribe,” recalled the Rev. Dan Aldridge, a local black nationalist who served as a mentor to Bethune. “But he spelled it wrong, E-I-B-O. You know young people, man.” Bethune had become fed up with “all the talk and no action” when it came to Detroit’s heroin epidemic. “Mark told me that the only way to stop dope traffic was to rip off the big dealers,” Aldridge said. “I disagreed with him and argued vigorously against his vigilante plan. But Mark was his own man.” Aldridge had brought the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader H. Rap Brown to town for a rally after the 1967 riot. Bethune became fixated on a poster of Brown hoisting a rifle in one hand and a black newborn baby in the other. THE PRICE OF DOPE, the poster read, IS DEATH.

At about one o’clock on the morning of November 29, 1972, William Moore, a 50-year-old gas station operator, was driving to a corner store to pick up some milk when he spotted James Ford, a 50-year-old “local hustler” who sold clothes and other items out of the trunk of his Cadillac. Moore decided to stop and buy a pair of shoes. As the two men chatted, Boyd and Bethune approached, flashing a pair of guns and forcing them into the Cadillac. Back at Bethune’s apartment, Moore and Ford were lashed to chairs, blindfolded, beaten, and asked “Who is the chief of the Black Mafia?” and “Where is the dope?”

Somehow, the older men managed to free themselves and leap from a second-floor window. During the escape attempt, Ford was shot and killed. When police arrived at Bethune’s apartment, they discovered guns, marijuana, “narcotics paraphernalia,” and “militant and anti-narcotics literature.” The cops concluded that Boyd and Bethune must have been addicts. “When youth hang around people in narcotics and act like people in narcotics,” a high-ranking official told the Free Press, “we can only assume you are in narcotics.”

Five days later, Boyd and Bethune—this time with Brown in tow—decided to kidnap the wife and the girlfriend of a major heroin wholesaler. They had come up with the idea after watching the movie Shaft.

By that point, STRESS had finally “found a groove,” as Raymond Peterson put it. A week after he shot Dallas Collins, Peterson encountered a transgender prostitute while walking point on Charlotte Street. Suspecting the solicitation might be a set-up for a robbery, Peterson followed the “female impersonator” into a nearby apartment and found “two homosexuals in bed.” After Peterson told the men, “Hey, none of this,” they dressed and departed, leaving the prostitute to negotiate a price for sex. Since Peterson had no desire to make a vice bust, he started to beg off. Suddenly, the two gay men returned, one waving a knife. Peterson shot the man, Herbert Childress, twice, fatally—the first killing by a STRESS officer.

Two weeks later, Nathaniel Johnson, a 21-year-old janitor for the Detroit Public Library, and his friend Clarence Manning, 25, encountered STRESS officer Michael Worley disguised as a hippie in old clothes and a beard. Worley claimed Johnson, who had no criminal record, threatened him with a gun; Johnson said that Manning had stepped out of his Buick to urinate and had exchanged words with the “hippie” lingering nearby. What happened next wasn’t disputed: Worley and his back-up crew, including Raymond Peterson, shot Manning, who was holding nothing more than an empty beer bottle, seven times. It was Peterson’s bullet to the heart that most likely killed him. Johnson escaped in Manning’s Buick. When he returned to check on his friend, the police arrested him for armed robbery, though they never found a gun, and a jury ultimately acquitted him.

Over the summer and fall, the body count continued to rise. On July 5, 1971, a team of STRESS officers, including Peterson, fatally shot Horace Fennick and Howard Moore as the two men fled after an attempted robbery; one of them allegedly had a knife. On July 14, a team of STRESS officers, including Peterson, fatally shot James Smith as he and an accomplice fled after an attempted robbery; one of them allegedly had a knife. On September 9, Peterson fatally shot James Henderson, who allegedly pressed a knife to the throat of another STRESS officer during an attempted robbery. (Henderson, it turned out, had been the “female impersonator” who solicited Peterson before the Childress shooting.) On November 14, a team of STRESS officers, including Peterson, fatally shot Neil Bray after he allegedly used a broomstick to attack an officer disguised as a hippie. “I thought at the time he was armed, because he had an object in his hand,” Peterson later said.

In all, 13 Detroiters, all but one of them black, died at the hands of STRESS officers between April and December 1971. “During the first year of STRESS’s operation, the Detroit Police Department chalked up the highest number of civilian killings per capita of any American police department,” Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin observed in their 1975 book Detroit: I Do Mind Dying.

Peterson, for his part, sounded unapologetic when he spoke to the Free Press in 1976 about the early days of STRESS. “Nobody could get away from us,” he said. “No matter which way the son of a bitch turned, somebody could get him—he ran into somebody’s arms.” STRESS training included trips to the firing range, with officers making split-second decisions to pull the trigger based on flash cards depicting perps, both armed and unarmed. “My reaction time got quicker and quicker,” Peterson said. He snapped his fingers. “You’re supposed to determine that quick whether you’re going to shoot or not.” In the end, he groped for a familiar metaphor. “They kind of tune you like an engine, you know?” he said. “What the hell can they expect of you?”

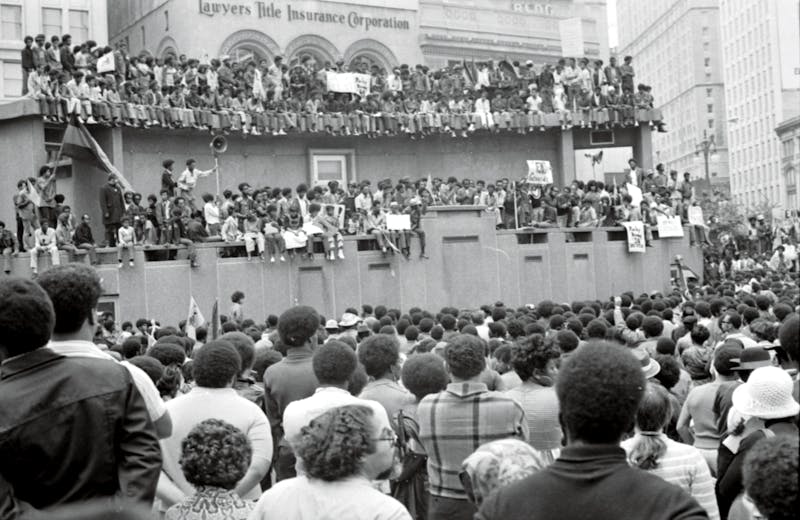

In September 1971, a police-reform group called the State of Emergency Committee led a demonstration of more than 5,000 Detroiters calling for the abolition of STRESS. The group’s spokesman was Kenneth Cockrel, who had already earned a reputation as the city’s leading radical activist. Cockrel, who grew up in a mostly black Detroit suburb, lost both of his parents when he was twelve. A few years later, he dropped out of high school and enlisted in the Air Force before enrolling at Wayne State. In 1968, he passed the state bar and co-founded the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, a radical alternative to the United Auto Workers and other white-dominated unions that reigned in Detroit. “More than any other single individual,” Georgakas and Surkin wrote in Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, “he was identified in the popular mind and in the mass media as the personification of a serious black revolutionary.”

Cockrel’s reputation grew with a pair of high-profile court victories. In 1969, he won an acquittal for Alfred Hibbitt, a black separatist accused of shooting a white police officer during a gun battle that erupted at the New Bethel Baptist Church. The following year, Cockrel successfully defended James Johnson, a black Chrysler worker who showed up at his plant with an M1 carbine rifle and killed three supervisors. Without denying that Johnson had snapped, Cockrel shifted the focus onto the endemic racism and inhumane working conditions at what was one of the most dangerous plants in the country. Jurors visited the crime scene, where black employees regularly drew the worst job assignments (Johnson had toiled in front of a 120 degree oven); they also heard testimony that Johnson had witnessed a lynching in Alabama at age five.

Cockrel grew out his Afro and sported a black beret at rallies. “Even if you are not a revolutionary—even if you are a running honky dog of the capitalist establishment—you have to agree he handles himself with immense style and aplomb,” journalist William Serrin wrote in the Free Press. “He is brilliant and audacious as hell.” When a white judge cited Cockrel for contempt of court—he had been overheard describing the judge as a “racist honky” and a “honky dog fool”—it only added to his legend. “Half of the courtroom was filled with police and their supporters, and half with community folks,” recalls Ken Mogill, a young clerk at Cockrel’s law firm at the time. “You could cut the tension with a knife.” Cockrel went on to win that case as well.

With the rise of STRESS, Cockrel had found the ultimate foil—a state-controlled terrorist group, to his mind, and a near-perfect manifestation of white-supremacist repression. In a petition that eventually drew 30,000 signatures, Cockrel called STRESS “a murder squad with an unlimited license to kill and maim.” Word of the unit made national headlines in March 1972 with the so-called Rochester Street Massacre, when undercover STRESS officers burst into an apartment in search of illegal weapons and engaged in a firefight with a group of men playing poker, killing one and wounding three others. The men turned out to be off-duty deputies from the Wayne County sheriff’s department.

On the evening of December 4, 1972, a team of STRESS officers staking out a dope house on Stoepel Street noticed a Volkswagen circling the block in a manner they deemed suspicious. Though the driver had committed no traffic violations, the officers decided to pull the car over based on what they later called “police instinct.” Approaching in their unmarked car, the members of the STRESS team claimed they flashed their badges and identified themselves as police, only to be greeted with gunfire.

Hayward Brown, who was riding in the backseat of the Volkswagen, later offered a conflicting account. He said he’d come to the house on Stoepel with his cousin John Boyd and their friend Mark Bethune to carry out their bizarre, Shaft-inspired kidnapping scheme. But Jack Crawford, the heroin dealer whose wife and girlfriend they planned on snatching, ended up being home. So the self-styled vigilantes decided to kidnap Crawford instead. Just then, a group of white guys tapped on their car window. Then a bullet whistled past Brown’s left ear. The white guys had started shooting, without identifying themselves.

However it started, the shoot-out ended with all four STRESS officers wounded, and the Volkswagen tearing off into the night. One officer, Richard Grapp, lost most of a lung after being struck in the upper chest. The police traced the identities of Brown, Boyd, and Bethune through their getaway car, declaring them “armed and extremely dangerous.” The suspects, police warned, were “professional triggermen” who had bragged to friends that they would “shoot any police officer on sight.” The STRESS team had potentially interrupted “either a major heroin transfer or an execution attempt on a known dope dealer.” A $6,000 reward was offered for information leading to their arrest.

Police unleashed an intensive manhunt in black neighborhoods where they believed the suspects might be hiding. Cops in flak jackets broke down doors without warrants and interrogated hundreds of black residents. Plainclothes STRESS officers killed Durwood Foshee, a 57-year-old former security guard with no criminal record, after they burst into his home in the middle of the night and he allegedly greeted them with a shotgun. Twenty police officers smashed down the door of Boyd’s parents’ home with a battering ram, rifles drawn, and detained the family for hours without charge. “They started yelling and screaming at me,” Melba Boyd recalls. “They told me what they were going to do to my brother—that if I didn’t help them, they’d make me identify his dead body.” James Bannon, the commander of STRESS, allowed that some police may have engaged in rogue “bounty hunting” during the manhunt. But the suspects, he insisted, were extremely dangerous. “No rational human being should object to answering questions about the whereabouts of these men,” he said.

Two days after Christmas, STRESS officers Robert Bradford and Robert Dooley ran across Bethune and Brown on Carlin Street during an unrelated robbery stakeout. Bethune shot and killed Bradford, a 25-year-old who had drawn lots earlier that evening so he could work overtime for extra pay. Dooley attempted to use Brown as a human shield, but Bethune shot him as well, leaving the second officer paralyzed and blind in one eye. Once again, Brown and Bethune escaped.

The following afternoon, an enraged Commissioner Nichols held his infamous press conference in which he branded the fugitives as “mad dog killers.” Homicide Sergeant Gil Hill, who would later play Eddie Murphy’s foul-mouthed boss in the Beverly Hills Cop movies, called the murder of Bradford an “execution slaying.”

But black Detroiters had had enough of STRESS and the ongoing manhunt. On January 6, 1973, the city council launched a probe of police misconduct, decrying “harassment of the black community in the search for these very dangerous killers.” A public hearing held on January 11 at Ford Auditorium drew more than 1,200 Detroiters, “mostly black, all angry,” according to the Free Press. When Commissioner Nichols attempted to read a statement, he was shouted down by the crowd.

The council heard testimony from citizens like the Rev. Leroy Cannon, who’d been awoken by a noise at his door at four o’clock in the morning on December 4. Assuming his teenage son had stayed out late, Cannon rose and prepared to scold him. Instead, he was greeted by a team of plainclothes police officers, who kicked in the door and shoved him against the wall. “Nigger, if you breathe too loud, I’ll blow your brains out,” one told him. The officers mistakenly believed that Cannon owned a white Volkswagen similar to the gunmen’s car. “I have a brown 1972 Cadillac,” he testified.

A man named Carl Ingram told the council that police officers had forced his fiancée to strip during an illegal search on December 7. “There ain’t no man hiding in her clothes!” he said. “If I had had a gun, I sure enough would have used it.” John Reynolds, the chair of a city task force dedicated to improving police-community relations, testified that his son had been stopped and beaten by police on New Year’s Eve. Kenneth Cockrel called on Mayor Gribbs to remove Nichols from his post and shut down STRESS.

But as with more recent debates over initiatives like stop and frisk, police brass countered with reams of crime statistics. The purpose of STRESS was to reduce robberies, they insisted, and the unit had been a resounding success. During their first year on the job, STRESS officers made 2,496 arrests and seized 600 guns. Robberies were down for the first time in a decade—by nearly 30 percent in two years.

Officers, meanwhile, discovered that killing unarmed civilians was a badge of honor within the department. “I was still lauded for what I was doing, even after the community started to get heavy on STRESS,” Peterson recalled. “They were happy with me. Whenever I shot someone, I would have to go to headquarters to fill out a report and the guys would cheer me when I walked in. The brass ... went out of its way to encourage me. I was a proud boy, you know? I was the fair-haired boy—as long as everything worked their way. Who doesn’t like to be the fair-haired boy? Who doesn’t like applause?”

On January 12, after the firebombing of the Planned Parenthood clinic, police captured Brown. When Melba Boyd met with her cousin at the police station, she recalls, his face “was so swollen it was a wonder he could even see.” Brown had a single request. “I want Ken Cockrel to represent me,” he told her, “because this has got to be a political trial.”

Eleven days later, Brown was transported from jail to Henry Ford Hospital. It was treated as a moment of high drama. Police were stationed on highway bridges along the route and secured the hospital parking lot as if it were a military base under siege. At Henry Ford, Brown was handcuffed to the foot of a bed holding Officer Robert Dooley, who had been paralyzed during the gunfight after Christmas. Dooley identified Brown, but admitted that he hadn’t witnessed him holding or firing a gun. Bethune, on the other hand, “was laughing at me,” Dooley said. “I was crawling on the ground, begging him not to kill me.” Cockrel denounced the heightened security measures surrounding the trip, calling them “Keystone Cops theatrics” designed to lend “credence to the commissioner’s statement that we are dealing with ‘mad dog killers.’”

John Boyd remained at large until February 23, when Bobby Davis, a black police officer in Atlanta, spotted him nodding off beneath a tree on the northwest side of town. After Davis approached to investigate, Boyd drew an M1 carbine from beneath his jacket. As the two men grappled over the rifle, Davis drew his own pistol and shot Boyd four times in the chest, killing him. Owen Winfield, Boyd’s half-brother, emerged from behind a parked car and began firing a .357 Magnum at Davis. The officer returned fire, killing Winfield with a shot to the head.

Two days later, a plainclothes Atlanta police officer received a tip that Mark Bethune had been sighted on the campus of Morris Brown College. When he found Bethune in a crowded dormitory lobby, the Detroiter dashed up a set of stairs and managed to reach the roof, where, according to the police, he drew his gun. The officer fired first, striking Bethune in the chest. Bethune then shot himself in the head. Newspapers printed a gruesome photograph of Bethune’s bloodied corpse lashed to a stretcher, ropes lowering it to the street. The Fulton County Medical Examiner later concluded that the barrel of Bethune’s gun did not appear to have been pressed against his head, which would suggest a highly unconventional suicide.

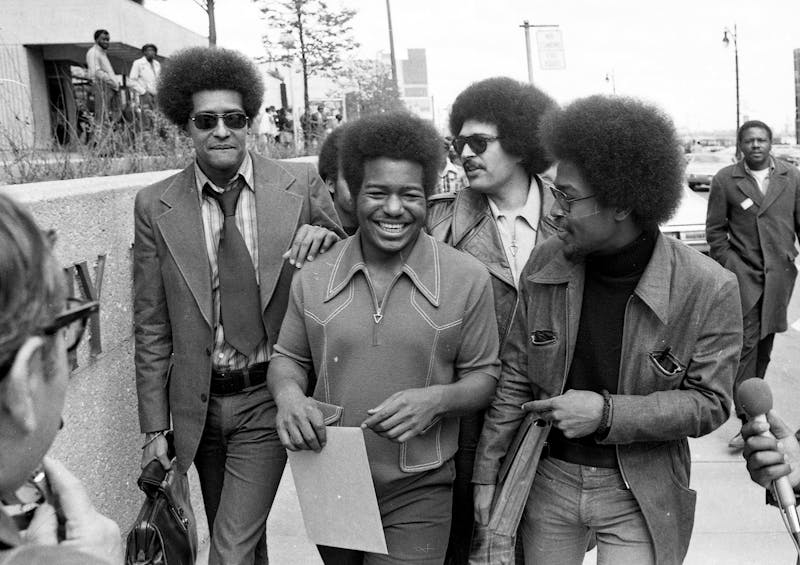

Hayward Brown’s first trial, for the attempted murder of the four STRESS officers during the botched, Shaft-inspired kidnapping attempt, began in May 1973. Hundreds of spectators crowded the courtroom—not simply “young militants with Afros,” Cockrel later pointed out, but also “mothers with babies, middle-class people, and old folks.” As one reporter recounted, Brown “emerged as a folk hero,” a symbol of public “frustration with the Detroit Police Department’s continuing STRESS unit and police inability to rid the city of drugs.” The previous month, 22 police officers had been accused of dealing drugs and accepting cash payments from heroin dealers. “I have seen and I have heard of police who have not only protected pushers but sold drugs,” Brown told reporters. He claimed he’d spent the past two years “persuading” dealers to quit by threat of force, that he’d stolen the dealers’ cash but always flushed the product. Cockrel added that Brown had “never taken anyone off”—meaning, he never killed anyone.

The trial lasted two weeks. One STRESS officer testified that he had seen Brown fire his gun; two others said they weren’t sure. Kemau Kenyatta, who had loaned the men his Volkswagen, also testified, telling the jurors how police officers, after tracing the car to his address, had beaten him and his wife and told him he was “a dead nigger.” Cockrel, in his opening statement, argued self-defense. The STRESS officers, he suggested, might have been caught up in the heroin-corruption scandal. Brown “had an understanding of STRESS,” he told the jury, which was “all the more reason to believe he might have encountered his end on December 4.”

Prosecutors dismissed the idea that Brown was an anti-drug vigilante, portraying him as a “cold-blooded cop killer.” But their arguments withered in the face of what the Free Press called Cockrel’s “quick wit and stiletto questioning.” After ten hours of deliberation, the jury—ten blacks and two whites—voted to acquit Brown on all charges.

Outside the jail, passers-by honked car horns and thrust fists into the air as Brown exited in triumph. “For once those mothers in STRESS got what they deserved,” a young black man told the Free Press. “They got caught at their own tricks. Maybe they’ll start thinking twice when they pull over a carload of spades who ain’t done anything illegal.” Brown’s case, Cockrel added, was “representative of questions that have seared themselves into the consciousness of the community.”

Brown, now a local celebrity, began making speeches at anti-STRESS rallies and on college campuses. His own face stared back at him from T-shirts in the crowds. But his trials were far from over. In early June, he returned to court to face attempted murder charges related to the shooting of Officer Dooley, who had changed his testimony after the hospital-bed interview and accused Brown of shooting him. Once again, though, Brown was acquitted, even though Cockrel called not a single witness on his behalf. “It was a weak case,” Cockrel said, “and the jury agreed.”

On June 27, Brown faced attempted murder charges related to his shoot-out with the Wayne State University security guards on the day of his arrest. Eager to avoid further humiliation, District Attorney William Cahalan became personally involved in the case, offering direct advice to his lead prosecutor. Multiple officers identified Brown as the man who had shot at them; police testified to finding two revolvers and 30 rounds of ammunition in Brown’s coat pocket when he was arrested. But once again, Cockrel argued self-defense, insisting that Brown, having been publicly excoriated as a mad dog killer by the city’s top police official, “had every reason to believe that the police would kill him on sight.” On the stand, Brown admitted to firing at the officers, but said he had deliberately avoided shooting to kill. He denied participating in the firebombing of the clinic, insisting that his “confession” had been extracted only after the arresting officers had beaten him with flashlights and their guns.

The jury, comprised of ten blacks, one Puerto Rican, and one Asian, acquitted Brown on July 6. Cheers broke out from the spectators. Jury foreman Stanley Leon, an autoworker at Ford, said the prosecution had failed to make its case. “When we went in to deliberate, I told the jury to forget about all feelings of race, color, or creed,” he explained. “I screened them in my own way to make sure that none of the people on the jury were anti-police. If I think a man is guilty and to my satisfaction the evidence is there, then he’s gonna be a dead duck—even if he’s my own son.”

In an extraordinary public rebuke, Cahalan denounced the verdict as a “miscarriage of justice” brought on by Cockrel’s rank appeals to “racial emotions.” Cockrel immediately fired back. “Cahalan is a classic example of those who applaud the system when it produces what they want, but go crazy when their own ox gets gored,” he said. “Persons who never had a word of criticism when all-white juries were sending black people, Puerto Ricans, and white working-class people to Jackson [a Michigan prison] are suddenly now becoming concerned and are threatening the abolition of the jury system.” Sixty-one local lawyers, all of them white, agreed with Cockrel, signing a petition that urged Cahalan “to stop attacking judges, defense attorneys, juries, and witnesses.” To drive home Cahalan’s double standard, Cockrel pointed out that there had never been a homicide conviction in Detroit of a white police officer for the killing of a black man. “The police,” he said mischievously, “must not countenance mad dog killers among their ranks.”

But Detroit wasn’t done putting STRESS on trial. Not long after Raymond Peterson shot and killed Robert Hoyt, he shrugged off the murder. “I don’t like taking another man’s life,” he told the Detroit Free Press, “but it seems that I am a magnet for trouble.” Peterson claimed self-defense, a difficult proposition to disprove before the era of dashboard cameras and smartphone videos. But by planting a knife on Hoyt, Mr. STRESS had slipped up: Forensic investigators, examining the knife, discovered hairs matching Peterson’s pet cat. He was arrested and charged with second-degree murder.

His trial began in February 1974. Selection of the jury, which included just two blacks, took 17 days. Peterson wore a bulletproof vest to court, and fellow STRESS officers packed the room in support. His partner, Gary Prochorow, testified that Hoyt had been driving at 100 miles per hour and that he’d been convinced the autoworker “was going to kill us both.”

Over two days of testimony, Peterson never denied shooting Hoyt or planting the knife. Instead, he insisted that his notoriety as Mr. STRESS had left him in “constant fear for his life,” and that he had received numerous death threats. His lawyer, Norman Lippitt, argued that the warping influence of STRESS had driven his client, almost inexorably, to murder. Peterson, he said, had been merely “acting as he was trained.” The system itself, not the officer, was to blame:

He was educated to respect law and order and to take orders. He was conditioned by the cruelty in the streets of this city, by the hate that permeates the very air we breathe. He was given a gun by an ignorant bureaucracy, and when he used it with fatal results, was lauded and praised by his narrow-minded, nonthinking superiors. The very men he was taught to respect and obey are the men who encouraged him and led him to this day.... A dead hold-up man is considered an accomplishment. Officers who kill them are congratulated, lauded, and given medals.

On February 27, Peterson was acquitted. Outside the court, he told reporters that he planned to celebrate with a vacation in Mexico. He was awarded $45,728 in back disability payments and allowed to retire with his full pension.

Before killing Hoyt, Peterson once asked a reporter, “What’s racism? You don’t like black people? You don’t like Polacks? I’m a Polack. I don’t take offense. My wife’s a Mick. What the hell’s a racist? A racist is something someone just wants to start an argument about. I don’t see why we all can’t just get together, black, white, yellow, striped, or purple. Our common problem is the world. If we don’t get together and do something about it, it’s going to go down the drain.”

While he was on trial for killing Hoyt, Peterson lost 50 pounds and acquired a heavy drinking habit. Two years later, he sat for a final interview with the Detroit Free Press. Reporter Tom Ricke described Peterson as a “haunted man” who spoke in a nearly inaudible whisper and detailed symptoms that, today, might result in a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Working for STRESS had left him confused, psychologically scarred, perpetually afraid. “I pay for it every day,” Peterson said. “I’ll be paying for it the rest of my life, for what the hell happened.”

In September 1973, two months after his own acquittal, Hayward Brown was arrested and beaten by three plainclothes STRESS officers during a traffic stop. The cops insisted they hadn’t been following Brown, although one of them, Donald Lewis, had been working backup with officers Bradford and Dooley on the night Bradford was killed. They had only stopped the car, they said, after they spotted Brown toss an envelope of what they believed to be narcotics out of the passenger-side window.

The powder in the envelope they claimed to recover turned out to be quinine, which can be used to cut heroin. The STRESS team also claimed to have found heroin in Brown’s sock and marijuana in his jacket pocket, as well as a handgun. On the ride to the police station, the STRESS team said Brown, while handcuffed in the backseat, reared up and kicked one of them in the back of the head, forcing them to pull over the squad car and use force to restrain him. Lewis and one of the other officers admitted to hitting Brown with their flashlights; the third officer said he used his hands. No mention of Brown resisting arrest, or of the officers striking him back, made it into the initial police report, though Brown was eventually taken to a hospital emergency room. The driver of Brown’s car, a woman named Bonita Burton, was not arrested.

In Brown’s version of events, the officers drove him to Detroit’s heavily forested, nearly 300-acre Palmer Park and beat him savagely. News reports described him as “barely ambulatory” when the officers dropped him at the hospital. He had to be helped up the steps, and his mother said he was unable to turn himself over in his hospital bed; bruises covered his head and stomach, and his entire right arm was soaked in blood. Cockrel said the officers had meant to kill Brown but somehow “messed it up.” STRESS commander Bannon defended his men, astonishingly, by pointing out that they “hadn’t been that inefficient in the past.” They could have easily killed Brown, he argued, had they intended to do so.

Despite the beating, Brown was charged with illegal possession of narcotics and a firearm. A jury freed him after deliberating for five minutes.

Not long after his fourth acquittal, Brown went to live with relatives in the Compton neighborhood of Los Angeles. But he was forced to return to Detroit in April 1974, when he was indicted by a federal grand jury for the firebombing of the Planned Parenthood clinic. (In an ironic twist, the federal charges against Brown, which would have appealed to the average law-and-order conservative of the time, were only possible thanks to Planned Parenthood’s federal funding.) Because the trial was taking place in a U.S. district court, the jury would be drawn from the suburbs as well as the city, and wound up including only four black jurors. Judge Cornelia Kennedy, a Nixon appointee, further stacked the deck against Brown by ruling that his “confession” to the firebombing in the backseat of the squad car was admissible.

On January 27, 1975, the jury found Brown guilty of the firebombing and he was sentenced to eight years in prison. Freed on bond, he would be vindicated three years later, when an appeals court overturned the verdict, ruling the confession inadmissible. Once again, Brown was freed.

His life, however, remained dogged by brushes with the law, and a series of arrests ensued: in 1978, for carrying a concealed weapon; in 1979, for possession of heroin and stolen property; in 1980, for possession of narcotics, carrying a concealed weapon, and armed robbery. After one arrest, Brown attempted to hang himself in his jail cell, fashioning a noose from the belt of his sweater. The police officers on duty cut Brown down, claiming they had no idea of his identity—when he’d been arrested, he had given his name as Robert Johnson—and that, after being resuscitated, he had complained of being “tired of all the hassles, tired of being arrested.” Brown denied he’d attempted suicide, claiming the police had been the ones who tried to hang him.

Then, in March 1981, he was arrested again, for possession of heroin. This time, as the Free Press put it, his “nine-year winning streak” came to an end. An all-black jury found him guilty, and he was sentenced to up to four years in prison. In jail, his political views shifted. “I thought it was white people’s fault, totally,” he told a reporter. “Now I don’t think it’s a black and white thing. It’s economic and classes—you know, people trying to get over, and others fighting to hang on to what they have.”

Three years later, after completing his sentence, Brown was dead—shot during an apparent robbery. The only witness, a 52-year-old Detroit man named John Harris, claimed that two men had attempted to steal his jewelry at a dilapidated four-story apartment building known as a neighborhood drug den. When one of the would-be robbers flashed a blue-steel revolver, Harris said, he managed to grab Brown and use him as a human shield. The gunman shot them both and fled the scene in a brown Chevy Monte Carlo.

Harris was struck multiple times in the chest. Brown, pronounced dead on arrival at Henry Ford Hospital, had been shot point blank in the face and neck. Police found eight packets of a white powder and $800 in cash on Harris. Brown had a watch, lighter, set of keys, black notebook, and $4 in cash. Police speculated that it was a drug robbery gone wrong. “It seems clear that they were trying to rob Harris, but he surprised the robbers,” a police spokesman told reporters. “He looks like an old man, but he must have had a little more spunk than they thought. The old man was a little too bad for them.”

John Nichols, the police commissioner who conceived and launched STRESS, laughed out loud when he was informed of Brown’s death. “I think probably the violence of his career terminated in the kind of justice he richly deserved,” Nichols said. “Not too many Detroit police officers will be sorry to hear about it. At least, I’m not. Ultimately, justice does prevail.” A news report noted that “police headquarters was flooded with telephone calls from police officers, including some from officers vacationing in northern Michigan, asking if it were true that Brown was dead.”

When Melba Boyd heard the news of her cousin’s death, she flew back to Detroit from Germany, where she had been on a Fulbright sabbatical. “Hayward was always less angry than I was, because he was wise about things,” Boyd says. “He understood it was not going to go away after he was acquitted.” From the beginning, she says, Kenneth Cockrel had warned Brown that black people who won cases against the police often ended up dead. Boyd once asked her cousin how he had survived so many beatings. In such situations, he told her, the key was to protect your vital organs.

Chokwe Lumumba, who had represented Brown, spoke at his former client’s funeral. “We’re not talking about a monster here,” he reminded mourners. “We’re talking about a man.” To a reporter, he noted that Brown’s fight against STRESS made him a target. “The police were scrapping for revenge,” he said, “and Hayward walks the streets of Detroit, which are alive with crime. So if they see him near some crime, they will charge him…. His options there, like other options of young blacks, were destroyed. That left the streets.”

Cockrel, who had become one of the most outspoken members of the Detroit city council, expressed a similar sentiment about his former client. “The brother never had a chance,” he said. “His father was an autoworker and his mother was a hardworking, decent woman. But the brother was out there on the street, and the street is a stern mistress.”

Shortly after Brown’s initial series of acquittals, a state senator named Coleman Young was elected the first black mayor of Detroit. He had run for office on the promise that he would abolish STRESS and fire Commissioner Nichols—who also happened to be his Republican opponent in the mayor’s race. “Nowhere, perhaps, has the issue of police conduct in an age of high crime come to be so clearly focused as in Detroit,” The New York Times noted shortly before Young’s election.

True to his word, Young disbanded STRESS in 1974. The unit wound up costing the city more than $1 million in legal settlements. During its first year, STRESS was responsible for 90 percent of all killings by Detroit police officers. The final death toll, over the course of two and a half years, was 22. All but one of the victims were black. Over the same period, the unit conducted some 500 warrantless searches.

By the 1980s, crime in Detroit began soaring to new heights. But during the brief window between the end of STRESS and the onset of the crack cocaine epidemic, major crimes and murders both declined. A 1979 New York Times profile of Young called him “one of the most influential blacks in the United States,” and pointed out that not a single Detroit police officer had been killed in the line of duty in four years. By contrast, six officers had been killed in 1971, the first year of STRESS. (The article also admonished Young for being “occasionally uppity to whites both in public and in private.”)

Four decades after the trials of Raymond Peterson and Hayward Brown, those who fought to stop STRESS see little change in the tactics and mindset of many police departments, post-Ferguson. Kenneth Cockrel’s wife, Sheila, an activist who served on the Detroit city council, still has copies of a hand-drawn, mimeographed “cop-watching” manual that she distributed during the STRESS years to teach outraged citizens how to document police abuse with a Kodak 126 camera. “We knew the streets where people were being stopped,” she recalls, “and we’d get out and start taking pictures of the incidents.” Decades before the arrival of smartphones, cameras served as the first line of defense against billy clubs and police revolvers.

Cockrel views the resistance to STRESS and Black Lives Matter as part of the same arc of history. The video evidence of police misconduct that has emerged in recent years finally “provides the opportunity to unmask the lie that was told over and over again: ‘I thought he had a gun. I thought he had a knife. They came at me.’ I’ve been hearing these lies since I was 18 years old. And often, they’re lies told to cover up un-American behavior by police officers that’s racially based. What now happens for well-meaning people, particularly white people, watching this behavior unfold in front of their eyes, is that it puts them in the position of having to address what white privilege really means in this country. And that’s not a comfortable thing to do.”

Kenneth Cockrel, a persistent critic of Mayor Young from the left, remained skeptical of trying to “reform” the police. “Reformism is what is counterrevolutionary,” he said. “You do not write letters to attorney generals, meet with black police assistants, etc. You take over the police department and you take over the city.” Cockrel died of a heart attack in 1989. He was 50.

Raymond Peterson died in April of last year, at the age of 81. He still lived in River Rouge, a downriver suburb of Detroit. No media outlets seemed to take note of his passing, let alone his previous life as Mr. STRESS. In the final interview he granted, he admitted that he worried about the price he would pay for the people he killed. “What’s going to happen to me,” he wondered, “if there is a hereafter and I die and get up in front of the big boss and he says, ‘Hey, man, you were a little heavy on those people, weren’t you?’ ” He admitted to thinking at times, “You’re no better than a rotten murderer,” though his psychiatrists, he quickly added, always assured him, “No, man, it’s not the way you are—it’s the way you’ve been made.” He couldn’t seem to understand how a man like him, who had been raised “with a lot of love for everybody,” could end up “out on the street killing people, and it not really bothering me.”

“I’ll tell you,” he said. “If that ain’t sick, boy, I don’t know. I don’t know.”