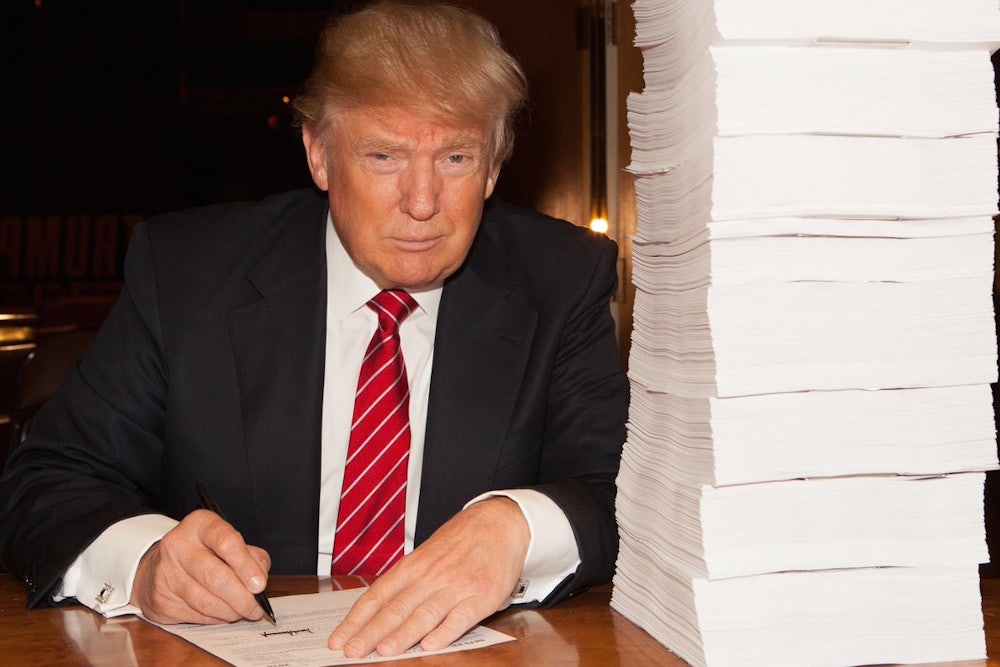

In the normal course of American political life, Tax Day plays a fairly limited role—an ideological emblem either of the yoke of government power or the obligations of citizens to contribute to the common good. President Donald Trump’s secrecy, and his unprecedented financial entanglements, have expanded that role dramatically. This year, the approach of Tuesday’s tax filing deadline inspired anti-Trump protests across the country, and renewed demands for the president to do what every president since Richard Nixon has done voluntarily and release his recent tax returns.

I did what was an almost an impossible thing to do for a Republican-easily won the Electoral College! Now Tax Returns are brought up again?

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 16, 2017

At his Monday briefing, White House press secretary Sean Spicer repeated the justification Trump has offered for withholding those returns from the public all along. “The president is under audit,” Spicer said. “It’s a routine one, it continues, and I think that the American public know clearly where he stands. This was something he made very clear during the election cycle.” Trump has asked the press to take this audit excuse at face value for almost two years, even as it is now within Trump’s power to ask the IRS to certify that he is, indeed, under audit.

Spicer, along with other White House officials and Republicans in Congress who are abetting Trump’s corruption, must be incredibly confident about the outcome of next year’s midterm elections.

Only the majority parties in the House and Senate have subpoena power. The chairmen of the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committees have power under the law to secure Trump’s tax returns and make them public. So although Democrats can’t promise voters huge legislative gains while Trump is president, they can credibly promise to address many of the ethical questions that have swirled around him since last year’s campaign—and that, if they’re not given control of one or both chambers of Congress, those questions will continue to go unanswered.

Trump’s tax returns will play a starring role in 2018 if for no other reason than that they symbolize the concrete stakes of the midterms: that only the Democrats will reveal his returns, if so empowered by voters; and that only Democrats will get to the bottom of Trump’s corruption more generally. It is an issue that will continually resurface until the election, after which the White House had better hope Republicans still control Congress. Because if they don’t, the potential consequences for their party in 2020 are nearly bottomless.

It is very likely that none of the people running interference for Trump have any idea whether he is legitimately under audit, or what he’s concealing by refusing to release the returns. But they have all placed themselves on the hook for whatever happens when the long fuse of the tax return story is finally lit.

Consider, for instance, that IRS Commissioner John Koskinen’s term ends on November 12. His departure will no doubt thrill conservatives, who have sought his impeachment over the agency’s alleged (but wholly imagined) partisan targeting of conservative non-profit groups. But it will create a major new conflict of interest for Trump, and, one imagines, a huge political problem for congressional Republicans: If we take Trump at his word that he’s been under continuous audit for a long time, he can’t be entrusted with the obligation to nominate a new commissioner.

It is true that the IRS has automatically audited all presidents since Nixon, and, unless Trump orders the agency to desist, will audit him as well. Thus, in an extremely superficial sense, past presidents filling vacancies at the IRS have faced a similar conflict. But Trump’s entanglements are sui generis. His predecessors had disclosed their tax returns and placed their assets in blind trusts, rendering the compulsory audit a mere formality. Trump has refused to liquidate his holdings, and, astonishingly, is using the existence of these corrupting financial interests as a shield to protect him from transparency norms that all recent presidents have adhered to.

If Democrats are smart, they will insist that Trump either get right with these norms or recuse himself from the selection of the next IRS commissioner—which he could do by, for instance, agreeing to nominate the consensus pick of the Republican chairman and Democratic ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee. Democrats should also refuse to consider any tax-reform legislation until its effect on Trump’s finances can be determined. It is unlikely that such legislation will garner much if any Democratic support anyhow, but it shouldn’t be lost on voters that Trump will have a huge hand in shaping legislation that cuts his taxes by an amount that only he knows, and Republicans in Congress are happy to help him enrich himself.

These aren’t necessarily fights Democrats will win, but they are fights that should frighten Republicans up for reelection in 2018 and 2020. Whether it’s two years from now or not, Democrats will eventually have the authority to sort all of this out. Why anybody would want their name associated with whatever those future inquiries turn up is beyond me. It is Trump’s prerogative to lie about his past audit status, or to block the IRS from auditing him in the future, or to hide whatever it is in his tax returns he doesn’t want people to see—and to keep doing these things for as long as he can. But we know to a near certainty that he can’t do it forever.