Chinese President Xi Jinping met this week with a powerful American leader who believes climate change is real and wants to open the economic floodgates for U.S.-China cooperation on green tech.

I’m not kidding.

While reporters struggled to find out if President Donald Trump has any knowledge of climate science in the wake of abandoning the Paris climate deal, California Governor (and prominent Trump critic) Jerry Brown was posing for photos with Chinese leaders—and pandas—in a full-frontal offensive to position his state not only as a leader on climate action, but as a quasi-nation-state looking to fill the void in reliable American leadership created by Trump.

He signed climate pacts with regional officials in Chinese provinces Jiangsu and Sichuan, met a slew of Chinese government ministers, and inked a major agreement with the central government to boost direct China-California cooperation on renewable energy, zero-emission vehicles, and low-carbon cities. Brown appeared with energy ministers from 24 countries and the European Union at this week’s Clean Energy Ministerial in Beijing, and his delegation is scheduled to meet 75 Chinese companies interested in working with California.

Another focus in Beijing is a side-event for the “Under2 Coalition,” a group Brown helped found in 2015, which now consists of 170 “sub-national” jurisdictions in 33 countries (including two Chinese provinces) committed to fighting climate change.

“The key to Paris was President Xi and President Obama meeting together,” Brown said in Chengdu earlier this week, according to the Los Angeles Times. Now, “it’s up to President Xi to advance the ball. We want to stand behind him and make that possible.”

"It's complicated to bring panda bears" to the US, Brown says on tour. "You have to know a lot of powerful people." pic.twitter.com/b5YPd8QvWg

— jessicameyers (@jessicameyers) June 4, 2017

In contrast, Trump railed against China last Thursday when he committed to leaving the Paris deal, casting the United States as a victim of an international conspiracy to steal U.S. jobs. “They can do whatever they want in 13 years, not us,” he said of China’s emissions plans. (That is not true.)

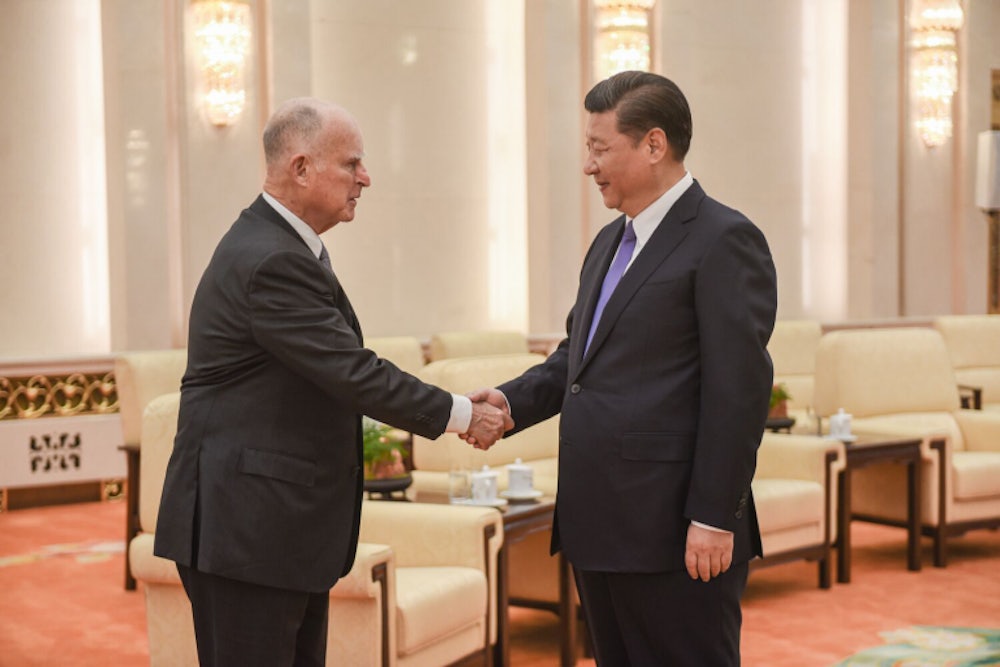

China, known for being a stickler for diplomatic protocol, spared no symbolic expense on Brown. Xi met the governor in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing and spoke to him in a closed-door meeting for 45 minutes. State media, which hews religiously to the official script, gave the sort of account normally reserved for visiting heads of state, imposing an entirely different subtext on Xi’s boilerplate language about U.S.-China cooperation.

“Since the two countries established diplomatic ties, China-U.S. relations have weathered various tests and always moved forward, bringing huge benefits to both peoples,” Xi said. “Bilateral relations also contributed a lot to peace, stability and prosperity of the Asia-Pacific region and the world.” Bilateral, in this case, with a non-national government.

“It’s very clear he welcomes an increased role on the part of California,” Brown said of Xi’s reception.

There have been no reports so far of Xi meeting the most senior U.S. government official, Energy Secretary Rick Perry, even though he’s in Beijing, too.

Jerry Brown’s engagement with Chinese officials dates back years but has become especially significant after the election of Donald Trump, says Orville Schell, director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society—and a biographer of Governor Brown.

“Trump blew everything up in the bilateral part of the climate relationship in Washington, which had become the keystone of the U.S.-Sino relationship,” he said, adding that California is “big enough, and brassy enough, and interesting enough to actually be able to pretend to act like a country.”

“America is truly missing” from the world stage, Schell said. “It’s an opportunity for the state of California to take up the slack where Washington has dropped the rope.”

But there are obvious limitations on California’s power. It may be, by some measures, the world’s sixth-biggest economy, but it can’t shape foreign policy by itself, nor staff an embassy, and Brown “can’t make unilateral commitments in the same way federal government can,” said Joseph Majkut, the director of climate policy for the Niskanen Center, a libertarian research group in Washington, D.C., that advocates market-based solutions to climate change.

“None of this is official, none of this is binding,” with the same sheer force of a national law, he said. “He’s the governor of Pasadena, not Pittsburgh.”

And yet, Majkut supports Brown’s activities in China and sees many opportunities for the governor to share the Golden State’s wealth of knowledge on carbon reductions and green technology. “There is a vacuum,” he said. “I think he has every right to step into it.”

Both Majkut and Schell agree it’s not hurting Brown’s political profile to establish himself as a key figure in resisting Trump, either. “Brown has always had a political gene that has been coded to go onward and upward on the political chain,” Schell said. “So it’s not ungratifying to find himself in a statesman role.”

For Brown it’s a win-win proposition: He is able to polish his bona fides as an international statesman and keep up political pressure on the Trump administration, Majkut said. “Before we left Paris, this was the issue of the left in any political sense,” he continued. “What is to be seen is how much this move, which is wildly unpopular with most of the population, with Republican voters, and nearly all of industry, invites backlash, and puts Republicans on the spot for a solution of their own.”

Meanwhile, Energy Secretary Rick Perry was at another Beijing conference on Tuesday, where he advocated the use of carbon capture technology—scorned by green groups as being only in primitive stages of development and therefore lacking the capability to slash carbon emissions right now.

“I don’t even know why he’s there,” Schell said of Perry, who has spoken fondly of fossil fuels and questioned climate science. “This is like taking the Antichrist into the cathedral.”

This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.