It is infuriatingly easy to imagine Senate Republicans passing legislation that throws millions of people off of their health plans to finance a tax cut for the wealthiest Americans this week, just days after introducing it—without holding a single hearing for debate and amendments, or waiting for a final impact analysis from the Congressional Budget Office.

That may not seem like it matches the available facts. After all, more than enough Republican senators have announced their opposition to the plan to sink it in an up-or-down vote. But the counterintuitive arithmetic of legislative horse-trading means that declaring the bill dead likely requires stiff opposition from twice the number of GOP senators needed to kill it.

Majority Leader Mitch McConnell can only afford to lose two Republican votes in the final tally. Three kills it. But unless three moderate Republicans and three conservative Republicans oppose it for mutually exclusive reasons—the moderates because it soaks the poor too much, the conservatives because it does not soak them enough—then it can’t be considered a dead letter. Over the course of the next several days, McConnell will try to pry reluctant members loose from their opposition with gimmicks and kickbacks. If three conservatives and two moderates oppose the bill, he can buy off the three conservatives, and vice versa.

Without a pincer movement like this, McConnell could race a substantially modified bill to final passage, long before CBO has weighed in on the effects of the changes.

Under the circumstances, and given McConnell’s determination to freeze liberals and the media out of the legislative process, there’s nothing concrete Democrats can do to change the mathematical problem. Most have concluded that their best options are to protest and delay and hope the backlash turns Republicans against the bill. But there is one other thing they can try.

On Friday, in a press conference with his state’s Republican governor, Brian Sandoval, embattled GOP Senator Dean Heller made it pretty clear that his vote is not gettable. Appeasing him would alienate more than one conservative on the opposite side. It is possible that Heller would like the bill to pass without his fingerprints on it, but he can’t let on that that is the case.

Separately, Republican senators Bill Cassidy and Susan Collins marked themselves as potential opponents of the McConnell bill, by teaming up earlier this year to draft an Obamacare alternative that wasn’t organized around the principle of transferring hundreds of billions of dollars in health spending dollars from the poor to the rich.

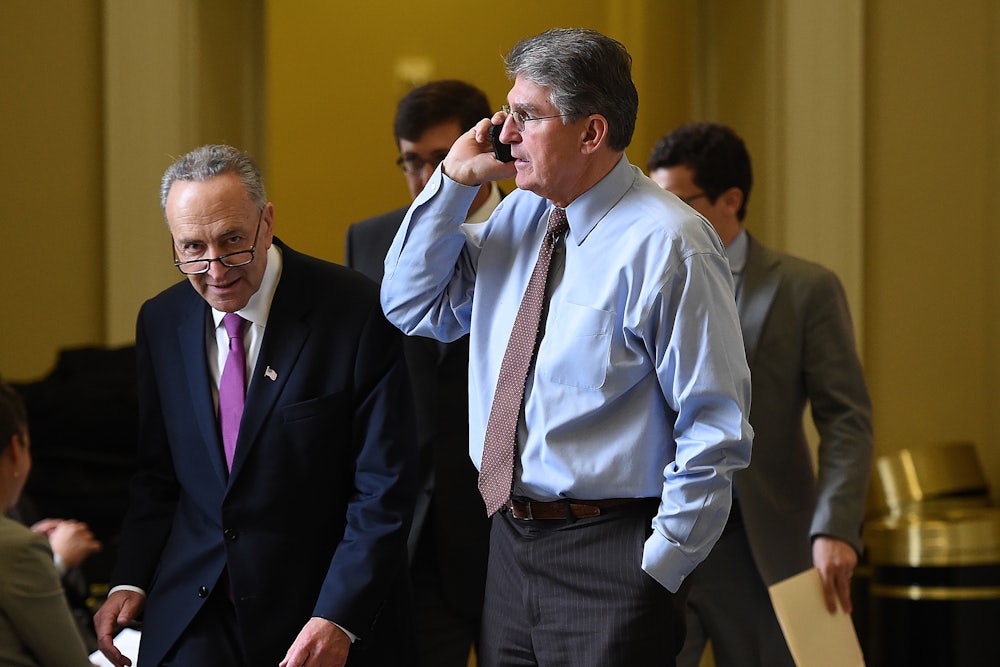

Rather than hoping support for the bill will unravel, conservative Democrats, with Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer’s blessing, can enlist these three (and perhaps other Republicans) in a discussion over that bill.

The Cassidy-Collins plan would preserve the revenue streams that finance the Affordable Care Act coverage expansion, and allow states to choose whether to keep Obamacare, switch by default to a system that automatically enrolls the uninsured into catastrophic insurance plan and a subsidized health savings account, or opt out of expansion altogether.

Earlier in the year, when Republicans seemed like they might repeal Obamacare much more rapidly than they’ve been able to, I argued that Democrats should engage in backchannel negotiations with Cassidy and Collins as a failsafe. Arguably January would’ve been too early to form a bipartisan health care working group. But with the Senate otherwise poised to pass a cruel and unvetted bill that would uninsure tens of millions of people, the time for such a working group couldn’t be more ripe.

Democratic senators like Joe Manchin, Claire McCaskill, and Heidi Heitkamp, all of whom face tough elections next year in states that Donald Trump won, could represent their party in the discussion. The most immediate value of such a negotiation would be to stop partisan Obamacare repeal in its tracks. As anyone who followed the 2009 debate over the Affordable Care Act knows all too well, these kind of senatorial gangs can waste a tremendous amount of time.

What would distinguish the 2009 game of six from today’s is that representatives of the minority party wouldn’t be negotiating in bad faith. It’s possible that the discussions would end in gridlock, and reopen the path to a more outright ACA repeal. But it’s also possible that the negotiation would widen and end in an agreement on far more modest health care reforms that don’t leave 20 million Americans exposed to health catastrophes and financial ruin.

If a bill like that passed the Senate, it’d be up to House Republicans to decide whether to take it up or leave Obamacare in place. That’s a much better outcome than the alternative we face today, which is that McConnell rushes his Trumpcare bill through the Senate at blinding speed, and the House sweeps the Affordable Care Act into the dustbin before the month is out.