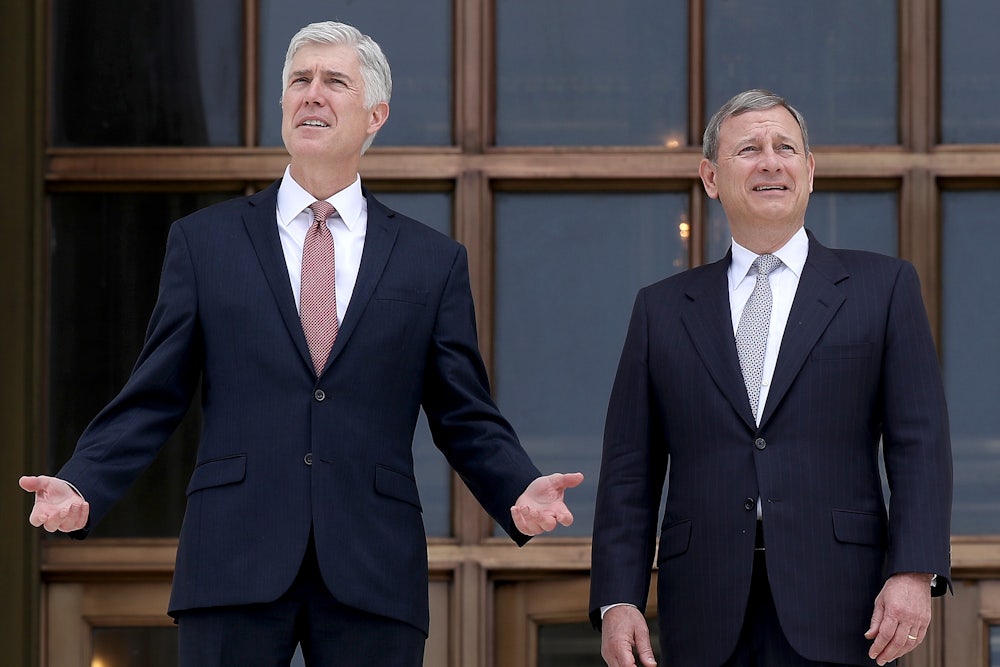

The Court today partially lifted an injunction on the administration’s 90-day ban of all travelers from six predominantly Muslim nations and its 120-day ban on all refugees. It also agreed to consider the constitutional merits of Trump’s executive order in October. Going in, we know that three justices appear ready to side with the administration. In an opinion concurring with the Court’s order, Clarence Thomas wrote that the injunction should have been lifted in full and that the administration has “made a strong showing that it is likely to succeed on the merits”—that is, that the rulings by two appellate courts blocking the ban will be reversed. Thomas was joined by Samuel Alito and Trump appointment Neil Gorsuch.

The appellate courts—the 9th and 4th Circuits—ruled that the ban discriminated against Muslims, citing Donald Trump’s own words and that of his advisers. During his campaign, Trump had called “for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” As Chief Judge Roger Gregory of the 9th Circuit wrote in May, “Then-candidate Trump’s campaign statements reveal that on numerous occasions, he expressed anti-Muslim sentiment, as well as his intent, if elected, to ban Muslims from the United States.” The travel ban was thus deemed to be a violation of religious freedom.

The Supreme Court, however, felt that the blanket injunction went too far. Citing the claims made by the original plaintiffs in the two cases—which included an Iranian permanent resident seeking to reunite with his wife and a Hawaiian university that had extended admissions to students from the affected countries—the Court ruled that the ban cannot be enforced “against foreign nationals who have a credible claim of a bona fide relationship with a person or entity in the United States.” But for everyone else, including refugees fleeing war-torn areas, tough luck.

This is because, the Court said, the judiciary must defer to the executive’s judgements on issues related to national security. As the Trump administration noted in its legal brief, statute holds that the president can “suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens” to this country “[w]henever [he] finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens ... would be detrimental to the interests of the United States.” This is the power invested in the presidency, and the Court has long upheld that power. The order itself does not have the words “Muslim ban” scrawled all over it, and it is well within the executive’s right to bar entry to foreign nationals, a right it exercises on a daily basis. As the Court notes, “the Government’s interest in enforcing [the order], and the Executive’s authority to do so, are undoubtedly at their peak when there is no tie between the foreign national and the United States”—such as a spouse or a university or an employer.

There are several other issues at play, including whether the order is already moot (it had a sell-by date of June 14) and whether it’s temporary nature makes it more legally palatable. But at bottom is a separation-of-powers issue that has traditionally swung toward the executive, and that is unlikely to change with a conservative Supreme Court.