The opening lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’s epic “The Anniad” are, like the rest of the poem, deceptively uncomplicated. “Think of sweet and chocolate,” she writes:

Left to folly or to fate, / Whom the higher gods forgot, / Whom the lower gods berate; / Physical and underfed / Fancying on the featherbed / What was never and is not

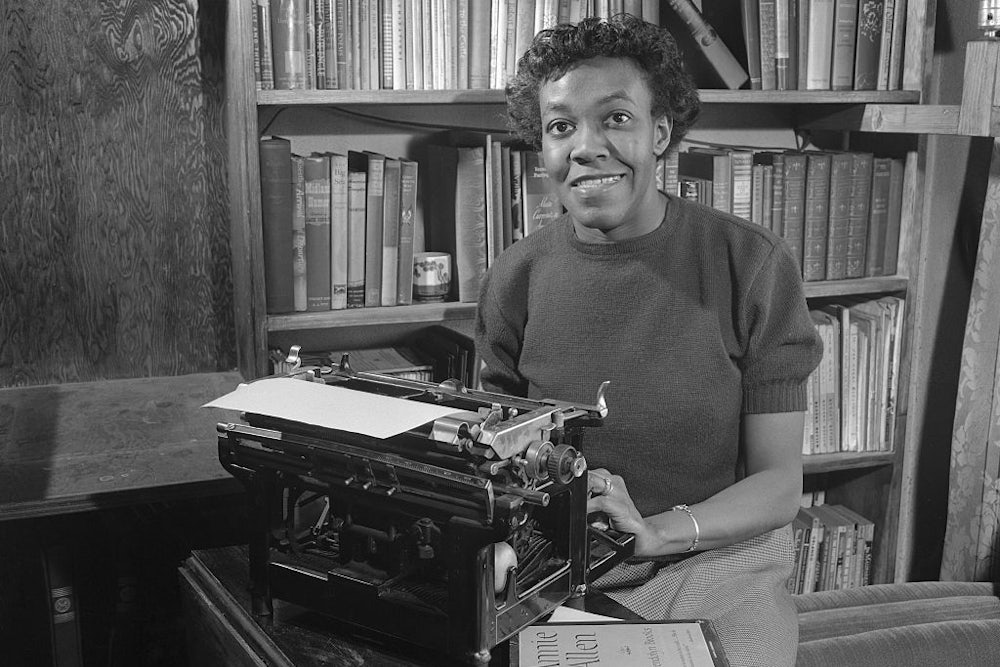

The poem, published in 1950, sweeps through the life of Annie Allen, an ordinary black girl who dreams of finding happiness and attaining self-consciousness in 43 stanzas. At the same time, Brooks details the social conditions that ensure Annie’s dreams remain unrealized, that force her to mature early, and ultimately leave her disillusioned. “The Anniad” takes place against the backdrop of World War II. While almost all Americans benefitted from the post-war boom—both economically and socially—African-Americans failed to reap the full benefits of a country still fraught with racial tensions. Annie Allen suffers the effects of the war: Her husband returns with post-traumatic stress disorder and a depressing awareness of the “white and greater chess” of America. He eventually abandons Annie, who is left “derelict and dim and done.”

Brooks won the Pulitzer Prize in poetry that year for “The Anniad” and the collection in which it appeared, titled Annie Allen. “No other Negro poet has written such poetry of her own race, of her own experiences, subjective and objective, and with no grievance or racial criticism as the purpose of her poetry,” one of the judges, Alfred Kreymborg, wrote of her work. “It is highly skillful and strong poetry, out of the heart, but rich with racial experience.” But that wasn’t what Brooks wanted to accomplish at all. When her editor Elizabeth Lawrence asked the young poet what inspired her to write, Brooks said “to prove to others (by implication, not by shouting) and to such among themselves who have yet to discover it, that they are merely human beings, not exotics.” “They” referred to black people in America, a population who in 1950 found themselves in the middle of the Jim Crow era and on the cusp of the Civil Rights era.

“They are merely human beings, not exotics” is another deceptively uncomplicated line. It came four years before Brown vs. Board of Education, the seminal court case that would yield its own slogan: “Separate is not equal.” It came five years before the death of Emmett Till, whose murder would spark a national movement. And now, nearly seven decades later, it feels like the first iteration of our insistence that “black lives matter.” Today’s movement to reassert the humanity of black people in America has grown alongside a forceful cultural push to highlight black people’s ordinary experiences. Television shows such as Insecure, films like Moonlight, and books such as Claudia Rankine’s Citizen do the work of helping others understand how one can both experience the effects of devastating social forces and live a full life. These very different works each examine the privilege to be un-fascinating.

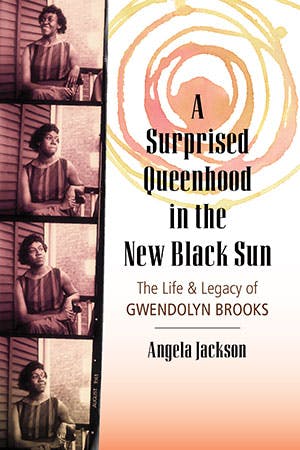

Any consideration of these everyday stories would be incomplete without Gwendolyn Brooks—who would have turned 100 this past June. Poetry magazine dedicated their June issue to Brooks and a handful of new scholarly books were released. Included in this pack is Angela Jackson’s A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life of Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks, a breezy biography that explores Brooks’s early activism and relationships with the women in her life—from her mother, Keziah Brooks, to her editor Elizabeth Lawrence. She provides criticism which situates Brooks’s poems in the social and political conditions of her time. What emerges is a portrait not just of a creative maverick, but also of an artist who constantly negotiated her womanhood and strove to tell the stories of ordinary black women.

Brooks’s story begins in Chicago. Though she was born in Topeka, Kansas on June 7, 1917, she moved to Bronzeville, Chicago when she was very young. It was in this midwestern metropolis that Brooks found her muses and began to write. She started young—her first poem “Eventide” was published in American Childhood when she was 13 years old—and maintained an impressively diligent practice of writing every day. Brooks’s mother Keziah Brooks recognized her daughter’s talent early on and once exclaimed that she was “going to be the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar!”

After graduating from Wilson Junior College in 1937, Brooks went in search of a job. She was 19 years old and was encouraged to interview for a position at the Chicago Defender, a newspaper that regularly published her poems. She wrote the publisher and upon meeting him was met with a coldness not felt in their previous correspondence. “If we hire you,” he said to her. “You will have to be on time every day.” She never heard from him after that day, and while the encounter did not sour Brooks’s determination to write, it highlighted the racism and colorism that frequently met her.

Between 1945 and 1949, Brooks’s career flourished. She published her first book A Street in Bronzeville, a slim collection of poems that included “the mother,” a then controversial poem about abortion, and “kitchenette building” a grim portrait of life in Chicago’s kitchenette buildings. The collection established Brooks as a critical voice in American letters. Her second collection of poetry, Annie Allen, experimented with more elaborate and difficult diction; the title of its main poem, “The Anniad” is a parody of Virgil’s Aeneid. Its formality demonstrated Brooks’s mastery of modernist form and her ability to manipulate language. It was an overt proclamation that the life of an ordinary black girl merited the same serious consideration as a Latin epic. In his review of “The Anniad,” Langston Hughes echoed the enthusiastic attitude of many critics toward Brooks. He wrote, “the people and poems in Gwendolyn Brooks’s book are alive, reaching, and very much of today.”

After the success of Annie Allen, Brooks began working on “American Family Brown” a series of poems that focused on the socioeconomic struggles of black Americans. The poems were initially rejected by her publisher and after much back and forth and revision, it became Maud Martha. A novel composed of 34 chapters in verse, Maud Martha tells the story of a young black woman living a normal life. She falls in love, marries, has dreams, and sometimes feels fulfilled. She is sad, but also happy. Her life, like many others, is composed of a series of mundane moments. Like Rankine’s Citizen, it’s a deft mix of meditation and observation. Maud Martha’s experiences highlight the sometimes unexceptional nature of being black in America. Its opening pages make clear the gap between the character’s life and her dreams:

What she liked was candy buttons, and books, and painted music (deep blue, or delicate silver) and the west sky, so altering, viewed from the steps of the back porch; and dandelions./ she would have liked a lotus, or China asters or the Japanese Iris, or meadow lilies—yes, she would have liked meadow lilies, because the very word meadow made her breathe more deeply...

Maud Martha is not an exceptional character. Brooks’s novel demonstrates how Maud Martha’s experiences of sexism, colorism, and poverty intersect with experiences of young love and adjusting to a new city. It is an attempt to show that “mundane scenes” even for black people “add up to a well-lived life.”

After the publication of Maud Martha, Brooks’s poems took a more overtly political tone and the politics of her personal life and her writing became more intertwined. She developed a deep interest in nurturing black literature, which led her to leave her publisher Harper & Row for smaller black-owned publishing companies. In the 1970s she joined Broadside Press where she published the rest of her poetry (Riot, Family Pictures, Aloneness, Aurora, and Beckonings) and the first volume of her autobiography, Report from Part One. In a chapter titled “Journeys,” Jackson chronicles the latter half of Brooks’s life, a period marked by her foray into the “current of Black Consciousness with her Black Community, her Black Family at large.” She spoke on the Women’s Liberation movement and like many black women at the time felt distinctly excluded from it. “I think Women’s Lib is not for black women for the time being,” she said.

She was right. After decades of telling the stories of the people around her, she now found her own voice was being drowned out. On a trip with fellow American writers to Kiev and Leningrad in 1982, Brooks was interviewed for an article called: “What It Means to Be Black.” During that interview Susan Sontag interrupted Brooks and began to give an answer. Brooks was taken aback. “Why do you turn from me to her with this question,” she said to the interviewer. “Obviously, being Black, I know more about what it means to be black than does she.” An enraged Sontag then told Brooks: “I turn my back upon you.” In this situation Jackson sees both Brooks’s “great sense of humor” and Sontag’s “sense of superiority and rage at her loss of white privilege to speak on behalf black people.”

At the end of her life, Brooks reunited with her husband Henry (they were separated for a period of time) and continued to shore up her relationship to her identity. She traveled to several countries in Africa attempting to build a connection with the diaspora while also continuing to read and write. She consulted for the Library of Congress before there was an official poet laureate. She hosted a range of writers for her reading series “before the word diversity was fashionable” and worked to lift “up the face of the real America.” Brooks remained active in her work—travelling and giving readings—up until her death in December 2000.

Gwendolyn Brooks understood the privilege of being ordinary long before it acquired the urgency it has today. The ordinary gives a sense of comfort—it is not to be feared nor questioned. It does not draw suspicion. The ordinary person can walk to the corner store, drive freely, and live without apprehension. For Brooks, the survival of black people in America depended on a lifelong insistence that they too were ordinary.