President Donald Trump’s decision on Tuesday to phase out Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the Obama-era program that protects young undocumented immigrants from deportation, already faces a legal challenge. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and 15 other attorneys general filed a lawsuit Wednesday accusing the Trump administration of violating the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by discriminating against “DREAMers” of Mexican origin. Trump’s order is almost certain to reach the Supreme Court, and it’s just as likely that Justice Anthony Kennedy will represent the deciding vote. Once thought to be among the Court’s more conservative justices, Kennedy has in recent years often found himself balanced on the point of a swing-vote spear. With this case, however, he will have two serious precedents to overcome: Yick Wo v. Hopkins, and his own words.

Yick Wo was one of the most unique, improbable, and pivotal civil rights decisions in American legal history. The case dates from 1880, when the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance requiring all laundries not constructed of brick or stone to obtain a special operating license. The board claimed this was necessary because of the extreme fire hazard created by laundries housed in wooden buildings. At the time, all but ten of the 320 laundries in San Francisco were wood framed, as were 90 percent of all the city’s buildings. While non-discriminatory on its face, this ordinance was directed at a specific minority: Three-quarters of the city’s laundries were owned by Chinese people, who dominated the business in the wake of the 1849 Gold Rush.

Anti-Chinese sentiment was rampant in the West. Moves to restrict immigration—at first applied only to manual laborers and “loose women”—culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law in U.S. history that prohibited a specific ethnic group from entering the country. Laws against the Chinese people already in America, like San Francisco’s laundry ordinance, were commonplace. After it took effect, 280 license applications were submitted. Eighty were granted, all to white owners. Not one Chinese laundry owner, out of the 200 who applied, was granted a license.

One of those denied was the proprietor of the Yick Wo laundry. He had come to the country in 1861, and had run his business for 22 years. Like many Chinese immigrants, he had never become a citizen (and then the Exclusion Act precluded the possibility). Although the Yick Wo laundry had passed inspections by both the fire wardens and the health department, the owner was ordered to close his business. He refused, was arrested, and then charged a $10 fine. When he declined to pay it, he was sent to jail. (There’s disagreement about the owner’s actual name, but it was not Yick Wo. However, in charging the man, Sheriff Peter Hopkins called him Yick Wo, thus the case name.)

The Chinese Laundryman’s Guild, which had become a powerful force in San Francisco, hired a top lawyer to appeal the 150 arrests of Chinese laundry owners who refused to close their shops. The case first went to the California Supreme Court, which sided with the city, and in 1886 it was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. The plaintiff argued that Yick Wo had been denied Fourteenth Amendment guarantees of “due process” and “equal protection of the laws.” The equal protection clause had never been the basis of overturning a law, but Justice Stanley Matthews, writing for a unanimous Court, used it to reverse Yick Wo’s conviction. The ordinance had been applied arbitrarily and in an obviously discriminatory fashion, Matthews wrote, and Yick Wo’s lack of citizenship made no difference—the amendment applied to “any person” under the jurisdiction of the U.S.

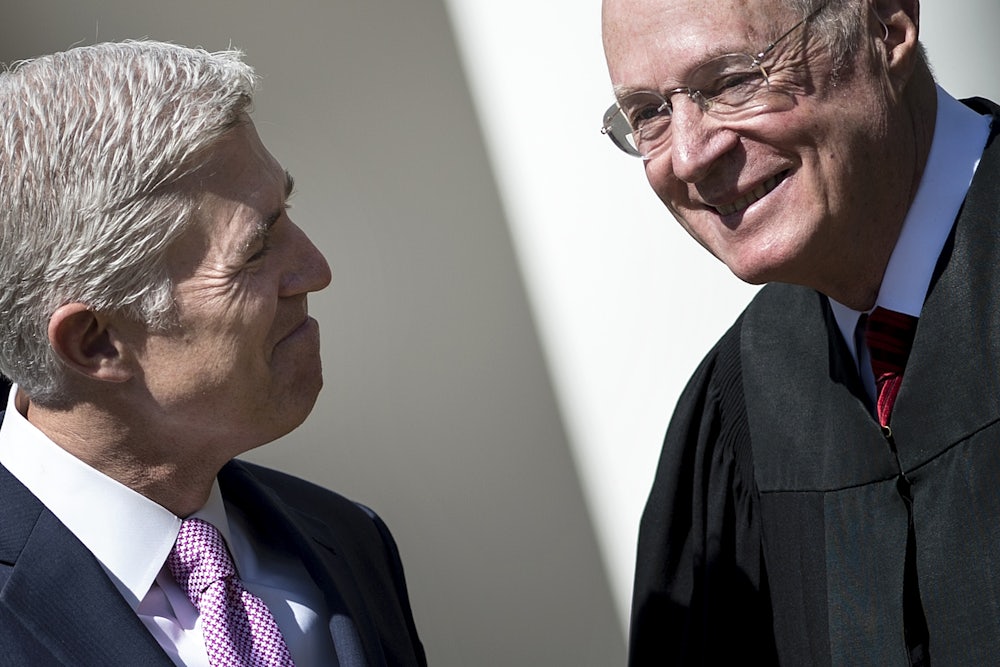

Yick Wo v. Hopkins has been cited more than 150 times in subsequent Supreme Court opinions—in cases ranging from apportionment to jury selection to loitering—and remains one of the most important civil rights cases in American jurisprudence. So important that the Lenore Annenberg Institute for Civics produced a 20-minute educational documentary on the significance of the case for use in schools—a film in which Justice Anthony Kennedy plays a starring role. “In its very first decision based on the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” the narrator notes, “the Supreme Court chose to protect the rights of a Chinese immigrant who was not a citizen.” To which Justice Kennedy adds emphatically, wagging a finger: “But he’s a person. And the Supreme Court of the United States read the Fourteenth Amendment, and you can read the Fourteenth Amendment… No person shall be denied equal protection of the law—not ‘no citizen,’ no person.”

In No. 78 of The Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton extolled the judiciary as the one branch of government that could “guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals” and to protect “the minor party in the community” from “serious oppressions.” We are now living in an age when the justices of the Supreme Court may be the only bastion against such oppressions. As such, it is gratifying to see Kennedy, in a video aimed at schoolchildren, passionately defend the Fourteenth Amendment rights of non-citizens. It would be even more gratifying to see Kennedy, if given the opportunity, choose to protect the “minor party” among those schoolchildren, the ones whose future in America is now very much in doubt.