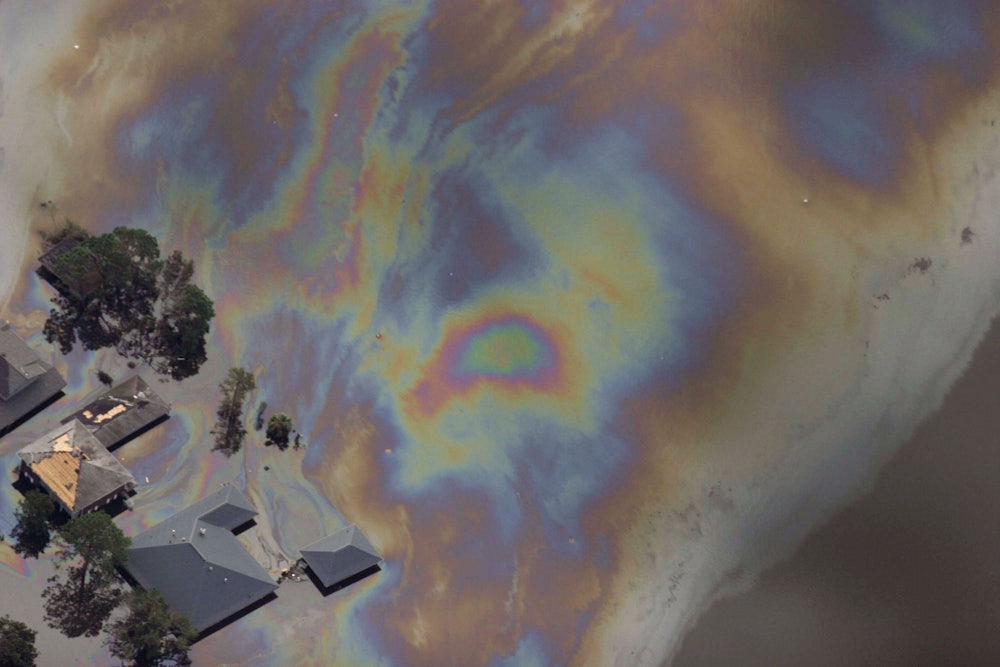

Hurricane Irma is probably causing severe déjà vu for first responders at the Environmental Protection Agency. Only a week ago, Hurricane Harvey brought record-breaking flooding to the Houston area, home to at least 41 of the nation’s most hazardous toxic waste sites. Water inundated 13 of these so-called Superfund sites, and now risks poisoning surrounding floodwater, soil, and people—mostly low-income, minority people, according to one analysis. Now, another storm that defies precedent is headed toward Florida and the Carolinas. There are at least 80 toxic Superfund sites in Irma’s path.

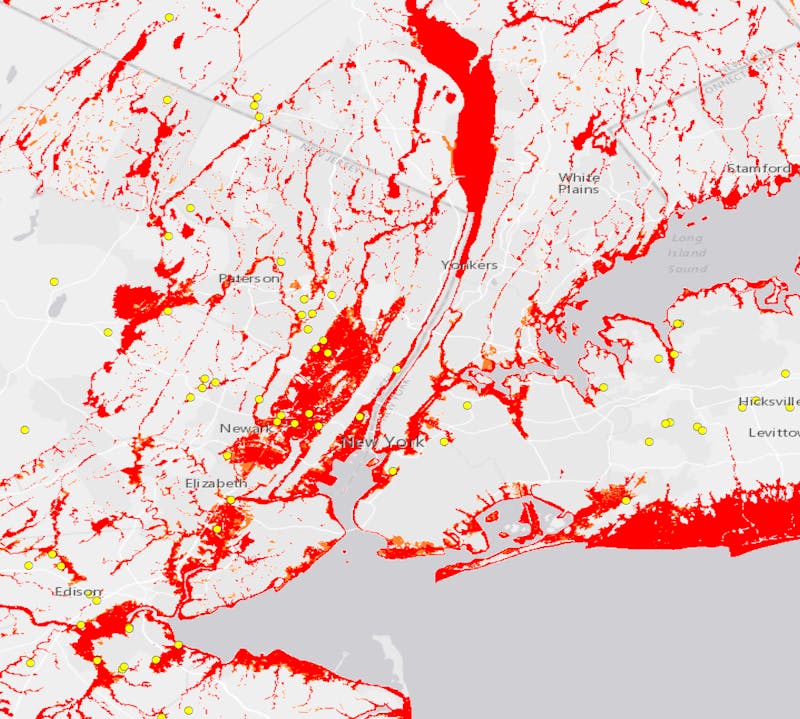

This isn’t a unique problem when it comes to hurricanes. After Hurricane Sandy devastated New York and New Jersey in 2012, officials had to monitor 247 Superfund sites—one of which, the Gowanus Canal, overflowed into people’s homes. Nine Superfund sites were in the path of Hurricane Katrina, and several flooded. Thomas Burke, an associate dean at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health who conducted an assessment of chemical exposures after Katrina, said these inundations very likely contributed to the mass of various chemicals found in soil and groundwater after the storm. “It’s hard to say for sure because there was not specific site evaluation data included in our assessment,” he said. “But absolutely, Superfund sites were a major potential source of soil and groundwater contamination. They always are after major hurricanes.”

But now that storms that are becoming more dangerous due to sea-level rise, a warmer atmosphere, and a warmer ocean, a growing number of polluted locations are at risk. In 2012, the EPA said that nearly a third of the nation’s federal hazardous waste sites were within a 100-year floodplain (an area with a 1-in-100 chance of a flood event in any given year, according to FEMA). Five years later, the number of Superfund sites has grown, and experts almost roundly agree that FEMA’s 100-year floodplain has been rendered obsolete due to climate change. Just look at Harvey, where more than half of the flooding happened outside of any flood zone—including FEMA’s so-called “500-year flood-zone,” where there’s supposed to be only a 0.2 percent chance of a flood happening. Three floods have happened in those 500-year zones in the last three years alone.

These supposedly rare floods are happening so often because rainfall is getting more intense due to climate change. But FEMA only relies on historical data—not projections for the future—to determine flood zones. This, according to Superfund experts, puts the EPA in a precarious position during hurricanes, for two reasons: first responders could be unaware of a toxic site’s vulnerability to flooding and not secure it properly before a storm hits; and the agency might approve cleanup plans that don’t consider flooding risk. “Flood maps are very important in informing the design, maintenance, and operation of remediation of a Superfund site,” Burke said. “If you’re in a flood-zone, effective cleanup is an entirely different challenge.”

Combine that with EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt’s climate denial, and some say that could be a recipe for a toxic disaster—if not during Hurricane Irma, then later on. “Addressing this threat effectively means acknowledging things are going to get worse with climate change,” said Peter DeFur, a longtime Superfund cleanup consultant. “Pruitt doesn’t want to address that.”

Pruitt appears to be aware that Hurricane Irma poses a threat to Superfund sites, and thus to human health. On Thursday, Bloomberg reported that approximately 77 people were working on “Irma related efforts,” with another seven on the way. “Technical staff are already working to secure about 80 Superfund sites in Irma’s path from Miami to North Carolina, including a former pesticide plant, military base and machine shop,” the report reads. Securing sites can mean a number of things: putting tarps over waste pits, cleaning and removing contaminated equipment, shoring up petroleum tanks, or building barriers around the area.

It’s vital to secure these locations before a storm hits. Superfund sites are all different. They can be former orchards where workers sprayed too many pesticides, or former paper mills that improperly disposed of asbestos. In Brunswick, Georgia, a coastal town that could be in Irma’s path, there’s a 760-acre site where oil and chemical companies seeped mercury, petroleum and polychlorinated biphenyls into marshes and soil for 80 years. The sites contain everything from sulfuric acid to heavy metals to waste oils.

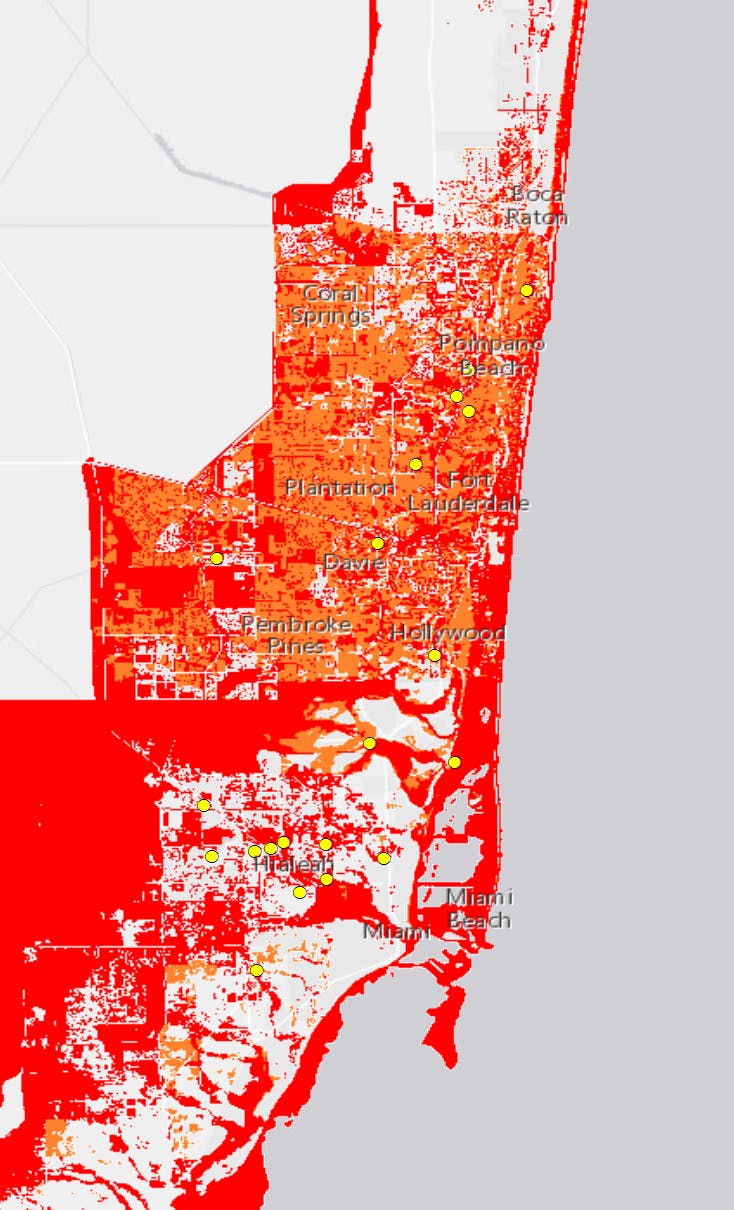

If these sites are not properly secured before a storm, there are a number of ways chemicals can spread. “You have a sequence of assaults—water, wind, and debris,” DeFur said. “Water gets driven into places that it hadn’t been before. These changes in the distribution in force of water effect what’s going on underneath the ground.” If chemicals get in groundwater, it can be difficult to track—particularly in southeast Florida, where the geological foundation is uniquely porous limestone rather than solid rock. “All bets are off there,” DeFur said. “We have no idea where things are going.”

In southeast Florida, there appear to be at least 20 current or former Superfund sites in and around FEMA-designated flood-zones, according to Dr. Kristy Dahl, a climate scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists. Using geographic information system mapping, Dahl combined floodplain data and Superfund site data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office for Coastal Management to show just how many sites were at risk from flooding. For these sites and those others that may be in Irma’s path, Pruitt said that the EPA would try to “make sure we apply the same type of approach we used in Texas.” But the EPA was criticized for its approach after an Associated Press story claimed the agency had not visited seven inundated Superfund sites. In response, the EPA attacked the reporter of the story, saying he was attempting to “politicize” the hurricane.

It’s still too early to know whether the flooded Superfund sites in Houston contaminated groundwater or floodwater and pose a threat to human health—and whether the EPA handled it correctly. But the EPA does deserve criticism for its apparent disregard for the growing threat to Superfund sites. Under the Obama administration, the EPA released a report acknowledging that increased severe weather due to climate change would put more toxic sites at risk, and proposed a plan to start addressing it. And yet, according to Bloomberg, the agency under Pruitt has “cut climate change preparedness efforts” at Superfund sites. EPA did not respond to our request for comment on whether it will continue efforts to prepare sites for climate impacts, but a spokesperson told Bloomberg that “the agency is refocusing its efforts on a comprehensive back-to-basics strategy that maintains core environmental protection with respect to statutory and regulatory obligations.”

The key phrase here is “back-to-basics,” which is Pruitt’s way of saying that the EPA is focusing on air and water pollution, not climate change. What that fails to take into account is that climate change risks causing more such pollution from America’s most toxic sites—not just during hurricanes, but during any natural disaster. “Hurricanes might be the ultimate threat, from the safe transportation of hazardous materials to the long term containment to most hazardous sites,” Burke said. “But that’s one part of the equation. We have worse wildfires out West near nuclear facilities and chemical storage sites. Droughts pose a hazard too. And so climate change has to be part of the thought of a process of environmental protection.” Pruitt can say he cares about physical pollution all he wants, but until he acknowledges this increased risk, he willingly puts millions of Americans at greater risk—while they’re already underwater.

Sharon Zhang contributed reporting for this piece.