Amidst the incessant clamor coming from the White House, it has been difficult for works of fiction to make themselves heard. An unlikely exception might be Moby-Dick, which is enjoying new relevance in an era that has been overwhelmed by the antics of one extremely volatile man. Our president has been compared to Ahab, a deranged captain steering the ship of state by the lights of his own obsessions. His supporters say the president is actually the white whale, the victim of deranged enemies who will stop at nothing in their monomaniacal pursuit of him. There is also something about Moby-Dick’s high passion and baroque prose that matches our fraught moment, which explains the popularity among political writers of the Twitter feed @MobyDickatSea. Several times a day the account will tweet a snippet from the book, and many of them are eerily apropos, such as: “But shall this crazed old man be tamely suffered to drag a whole ship’s company down to doom with him?”

It is always a good time to re-read Moby-Dick, but it is an especially good time to re-examine why it is so important, so oddly consoling, to see our world reflected in writing, even when that reflection is terrifying. The relationship between life and literature is the subject of Jean Giono’s Melville, a short, unclassifiable book (part essay, part novella, part biography) that accompanied the 1941 publication of Giono’s French translation of Herman Melville’s opus, and that is now being released in English for the first time. For Giono, literature and reality overlap the way that waves sweep over the shore, one ceaselessly refreshing the other and, in certain wondrous moments, giving it a glassy clearness. For instance, while reading Moby-Dick in the forests of his native Provence, he would feel “the trunk of the pine groan and sway against [his] back like a mast heavy with wind-filled sails.” Literature reflects, yes, returning the world to us, but also imbues our lives with its peculiar colors, and makes meaning of what would otherwise be meaningless.

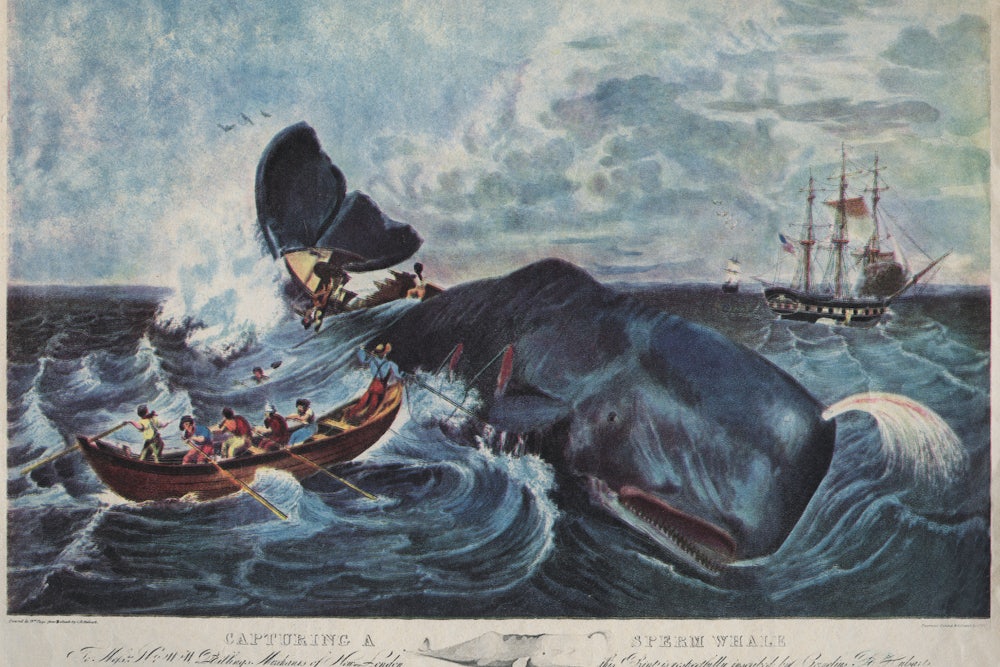

The color of a work of literature is the mind of its author, and this is what Giono, himself the author of many fictional works, has endeavored to explore. How does the character of an artist seep into his or her art? Giono’s Melville is largely a fictional account of Herman Melville’s 1849 trip to London to submit the novel White-Jacket to his publisher. There, he meets an Irish nationalist named Adelina White, who becomes a one-woman audience—a kind of ideal reader—for Melville’s flights of fancy as they journey across an English countryside that looks a lot like Giono’s French countryside. There is also a very brief künstelrroman in which a young Melville sets out to sea, providing fodder for a life’s worth of novels, and wrestles with an angel, a figure of divine inspiration who “illuminates the impenetrable mystery of the intercourse between humans and the gods.” This encounter informs all of Melville’s works, but particularly Moby-Dick, a novel about “somebody who eventually takes up the sword, or the harpoon, to start a fight against god himself,” as the fictional Melville tells a fictional Nathaniel Hawthorne when he returns to America.

Giono suggests that there is more than a bit of Melville in Captain Ahab, and that the character’s obsession with the white whale is a metaphor for the novelist’s own struggle with the great unknown: the blank pages that spread out toward the horizon like an ocean, waiting to be filled. Every book Melville wrote was a product of this struggle; every book was steeped in himself. As Giono writes, “His titles are, in reality, nothing but subtitles. The real title of each and every one of his books is Melville, Melville, Melville, again Melville, always Melville.”

Giono’s book is also called Melville, but, by his own formulation, it really should be Giono. And that’s what it is: the author seeing himself in Melville seeing himself in Ahab. There is a passage in which Melville purchases a pea coat at a secondhand store, the better to travel with outside London, and it serves as a symbol of what Giono is attempting: “The heavy jacket faithfully held its former owner’s form and gestures. Now Herman gradually filled it with his own. He knew, when he bought the old sea coat, he was buying a whole person.” Here is another way of thinking about the great unknown: as another human being, a mystery to everyone else, revealed only once he is inhabited, like an old coat. The idea that when we read a book we step into a new role, that we become another person, is contained in the famous first words of Moby-Dick—“Call me Ishmael”—a declaration made simultaneously by author and reader, one on the page, the other with his inner voice.

This is what Giono feels when he reads Moby-Dick, and it’s what we feel when we read Giono’s Melville. As the fictional Melville and Adelina White take long walks in the English twilight—the ideal time of day for Giono’s purposes, when one world is giving way to another—the line blurs between literature and reality, between the outside and the inside, between one person and another. Melville tells Adelina about the birch trees of his home in Massachusetts, and “she felt them in her heart.” He shares with her his private world, “which, in a completely natural way, became her world.” Their world is turned into words. Sensation becomes emotion. And two people, even if it is for the interlude of a heartbeat, feel as one.

If this all sounds too literary, too dewy-eyed, too removed from the urgent fact that our ship is barreling toward some awful fate, well, Giono would retort that there is no battle that occurs exclusively in the public sphere. “Even during times of peace (and likewise, in the midst of war), there are tremendous struggles one wages alone. This tumult is silence for everyone else.” We are in the world, but we are also in our heads. If Giono and Melville have shown us anything, it is that we can make this inner darkness visible—that we don’t have to go through all this on our own.