Sam Fox, Pamela Adlon’s television alter ego on FX’s Better Things, is not like a regular mom. She’s a cool mom. You know this because she dresses like Patti Smith, all steel-toed ranch boots and distressed canvas blazers, with a smudge of kohl around her eyes. She sometimes calls her three daughters “dude.” One night, after a Joe Walsh concert, she comforts her 16-year-old daughter’s friend, who has had a run-in with an ex-boyfriend. “If it is any consolation,” she counsels, “I see people I blew all the time.... You can either live with it, or not go out, or blow less people.” Sam’s daughter Max (Mikey Madison) is mortified. To be the progeny of the cool mom is both a blessing and a curse. It brings the freedom to wear a crop top to a church service (as Max does), but it can prevent your adolescent transgressions from playing out with the operatic drama you desire.

In the first episode of Better Things’ new season, Max has tried to shock her mother by dating a 36-year-old man named Arturo. They meet when he is dating Sam’s friend Macy, but he soon switches his attentions, promising Max he will take her to the running of the bulls. (He doesn’t.) The pair show up to a party at Sam’s large, Spanish-style bungalow. Mother and daughter scowl at each other for several minutes, until Max pulls Sam into the laundry room and admits that she’s in way over her head. Sam duly sees off the unwanted suitor, threatening to call the police. For Sam, who is a single mother of three daughters, navigating the balance between control and protection is both a daily practice and a survival tactic: Push them and they pull away, but fail to protect them and everyone loses. Better Things is, above all, a very funny show about motherhood and the mundane, the snarl of tedium and tenderness that fills the waking hours of a parent’s life.

If this mood-board displays shades of Louie, another half-hour comedy on FX, it’s because Louis C.K. is one of the show’s executive producers and co-creators. Adlon and C.K., longtime friends, began collaborating on HBO’s Lucky Louie, where she played his wife, and continued to work together on Louie, where she played Louis’s friend and unrequited love interest Pamela. When Adlon decided to make a show of her own, she chose, like C.K., to begin at home, mining her own life for material and then building out a fictional world on top of her own experience. Like Sam, Adlon is a single mother raising three daughters alone while carving out a life in show business (her most notable role, prior to Louie, was the voice of 12-year-old Bobby on King of the Hill). Better Things isn’t completely autobiographical: Adlon’s real family serves as more of a writing prompt than documentary subject. The show falls more into the category of autofiction: an auteur playing a version of herself run through a fun-house mirror.

Autofictional sitcoms have been floating around since The Dick Van Dyke Show, but the genre has become truly dominant in prestige comedy over the past decade. There are the shows starring men who play bizarro versions of themselves: Louie, Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, and Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm. And then there is Insecure, Issa Rae’s crackling HBO comedy, which grew out of her semi-autobiographical web series, Awkward Black Girl; British playwright Michaela Coel’s Chewing Gum; Tig Notaro’s One Mississippi; and comedian Rachel Bloom’s Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. Families and love interests drift in and out of these shows, but ultimately they aim to say something hyperspecific about their creators: what it is like to be a comedian, a young black woman in Los Angeles, a child of immigrants, or in Larry David’s case, a hapless narcissist.

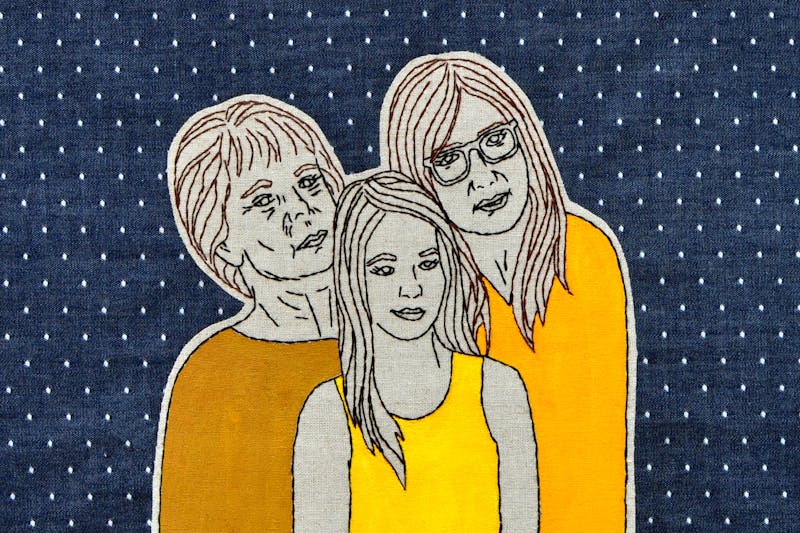

Adlon’s show traffics in this same specificity, but because it puts five women—Sam, her three daughters, and her mother, Phyllis—at the heart of the narrative, its universe feels both more complex and far less claustrophobic. It is less Louie and more like the work of Jenji Kohan or Jill Soloway, who with Orange Is the New Black, Transparent, and I Love Dick have embraced a broad spectrum of female experiences—and ages. Better Things is grounded in the minutiae of family life. It may be the most hyperrealist, purposefully casual portrait of teenage girls and aging women on television right now.

The multigenerational, all-female household on Better Things looks like Lauren Greenfield’s iconic “Girl Culture” photographs come to life. We see Max lazing around the den of the bungalow like a pampered cat, scrolling through Snapchat when asked to help carry a suitcase. We see her, with a pert hair flip, tell her mother to stay out of her life, only to turn into a puddle of anguish when she is gripped by insecurities. We see Phyllis (Celia Imrie), whose entitlement runs from charmingly batty to totally exasperating, pestering Sam to buy her a lavender suit at the hardware store—even though both women know that the hardware store will carry no such thing.

Phil, as Sam calls her, gets her own dedicated episode in the second season. After she is found trying to steal a priceless ancient artifact from the museum where she docents, Phil flees the property but cannot locate her car. Feeling embarrassed and out of control, she decides to leap into a manhole to cause an injury. Laid up in a hospital for five days, Phil finally has her daughter’s undivided attention, which is frequently laced with distraction and cruelty. (A devastating moment from the first season involves Sam bailing on a road trip with her mother after five minutes.)

In another scene, Phil taunts a young child in a bookstore for wearing a fake mustache and then proceeds to lose control of her bladder in the aisle. Her aging is not pathologized, but it’s still played for tragicomedy; as Phil is losing her grip on her body and her mind, Sam doesn’t suddenly soften to her mother’s whims. Instead, she plays the relationship with as much realism as I’ve seen. Having a parent in decline is often as frustrating as it is mournful: It’s logistics and patience and effort. There is, of course, love at the base of all this work, but Adlon never sugarcoats aggravating family moments with a group hug. That Sam loves her kids, and loves her mother, is widely apparent: The entire show is about how she grapples with being the center of gravity for four separate, insatiable maws of need.

Adlon likewise gives the adolescent dramas space to breathe without taking them so seriously that they feel maudlin. Sam’s middle child, Frankie (Hannah Alligood), is a sardonic, self-righteous teen who wears baggy clothes and goads her sisters ruthlessly. When Frankie is sent home from school in the first season for using the boys’ bathroom, she tells Sam that it’s not because she wants to be a boy, but because she was disgusted by the behavior in the girls’ bathroom, where one classmate “stuck her finger up her pussy.” In season two, Adlon doesn’t dwell on Frankie’s gender identity as a major plot point—just as a teenager living in a bohemian Los Angeles enclave in 2017 likely wouldn’t. Frankie’s life doesn’t turn into a Very Special Episode due to one unjust school punishment, but rather continues apace, with microdramas that have nothing to do with how she wears her hair.

In one episode, Sam feels underappreciated and lashes out at her two oldest daughters, demanding that they stage a faux-funeral for her so she can hear their eulogies while she’s still alive. Frankie, in her tribute, hints at how she has relied on Sam to help her through emotional tumult, admitting that “I would unload on her—Mom, where are my socks, or whatever—because I needed to give her some of my pain, because I knew she could carry it when I couldn’t.” We know Frankie is in pain, as any teenager moving through the world is in pain, and Adlon—who directed every episode of this season—finds a way to show it without resorting to either pathos or overanalysis.

If the first season of Better Things had too much of anything, it was gravity. It reveled in the prosaic heartbreaks of day-to-day life, without much surrealism or fanciful reprieve. And while it was always propelled by Adlon’s charisma, which is radiant, the show felt moored to Sam’s maternal struggles in a way that didn’t allow viewers to appreciate her prismatic qualities. We seldom saw her doing her job, or out on a date, or with friends, without her daughters around. The second season provides a bit of a corrective: The majority of one episode is devoted to watching Sam in her work as an actor, teaching a scene study class and filming a car commercial. She also takes more romantic risks this season. The second episode features a caustic breakup scene in a parking lot that, on its own, should earn Adlon another Emmy nomination.

It’s in showing Sam in love, with all the complication it brings, that Better Things really does something new with motherhood on television. In a scene that begins with Sam in bed in the morning, we see flashbacks from the night before, when Sam met a man named Robin, a weathered but handsome divorced dad, at a depressing book reading. As Sam stares at the ceiling, we see a replay of their night together, including a walk under street lamps and getting a drink. This all appears like a montage from a rom-com, even as—back in reality—Sam’s two oldest daughters start to paw at her feet for attention. Their squabbling and silly jokes play underneath Sam’s daydreams like a soundtrack. Even as the mother allows herself to fantasize, her family is always there, clinging to her legs.

The scene is beautiful, almost meditative. Adlon allows us to conceive of a world in which a single mom isn’t torn between her Romantic Desires and her Mothering Responsibilities. She finds a way to reconcile these parts of herself, conveying all the ways in which most of the people she meets are trying (and often failing) to reach the same balance. Everyone in Better Things is a little bit damaged, which means that the mother is not the only frazzled mess on screen. In granting all her characters a brokenness, Adlon breaks open the stereotype of a working mother and shows her in full relief.