A very old man lives in a castle with three beautiful young women who look almost exactly alike. They’re his playthings but since he is so very old he doesn’t seem to want to play with his toys that much. When he does, though, he likes to slather them in baby oil—which dissolves latex condoms, and may encourage Candida species colonization and thus lead to yeast infections.

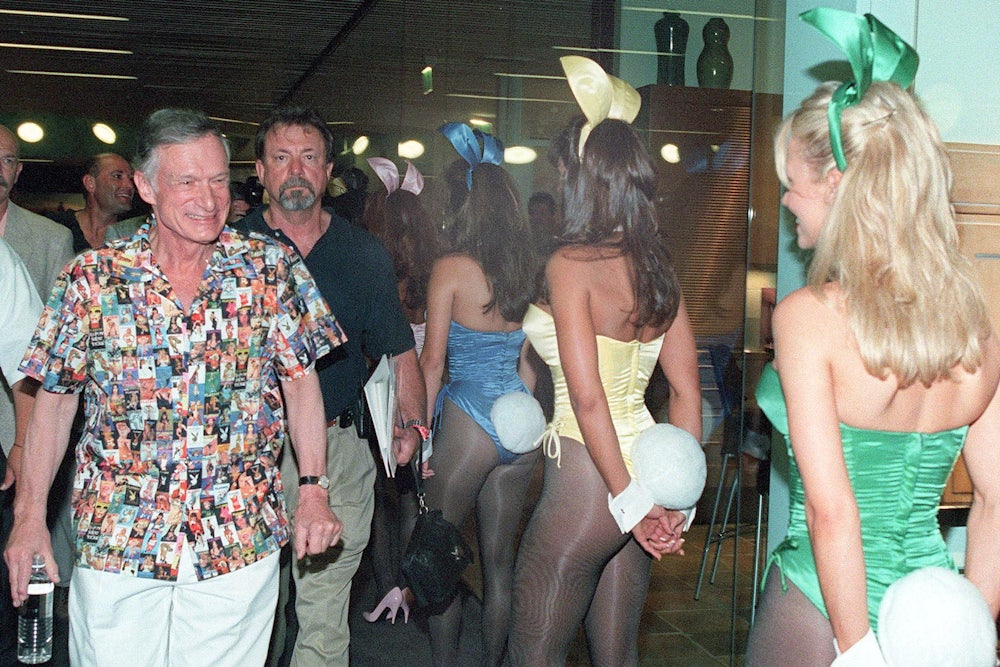

On the occasion of Hugh Hefner’s death at 91, we can see his pneumatic mansion through a few different lenses. The story above is a true one, but it sounds like the first half of an Angela Carter fairytale. Like a fairytale, it concentrates the diffuse attitudes of the culture down to a little plot that goes on inside a single building. As in the story of Bluebeard, the generalized dominance of men becomes cartoonishly horrifying. Hefner’s TV show The Girls Next Door ran from 2005 to 2010, and for its first (and most successful) five seasons followed the lives of “Hef” and three of his “girlfriends”: Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt, and Kendra Wilkinson. Madison appeared to be the most devoted girlfriend. In her autobiography, Madison wrote that, “I had to accept that I kept quiet about my life at the mansion because I was ashamed. I wanted people to believe the fantasy version because for so long I wanted to believe the fantasy. It was a far safer history than the truth.”

This is one aspect of Hugh Hefner’s legacy, and the most striking one: a coercive, unsafe house where young women were kept under contract and required to maintain physical appearances that take a lot of work. The only vengeance enjoyed by these fairytale heroines is the freedom of speech conferred by their expired non-disclosure agreements. But there are other legacies, too.

The most important achievement of Hefner’s life was Playboy, the magazine he created in 1953. The magazine’s venerable age means that it is often credited with “ushering in” the so-called sexual revolution, reflecting the “desires of the postwar generation.” It also means that Playboy helped to dictate the form of those desires. Although historians like Elizabeth Ferratigo have written about Playboy’s role in the twists and turns of America over the last half-century, it is very difficult to get real analytical purchase on something so big and so mainstream. There’s no way of knowing what America would have been like without Playboy, so the credit Hefner gets for inventing the modern idea of sex often feels a little overblown.

Playboy was sometimes a really great magazine. A close friend of mine is a big design nerd, and owns a bunch of issues from the 1960s. They are extraordinary documents to pore over now. The advertisements alone are like hieroglyphs: endless full pages selling elephantine audio equipment, brands of beer, cigarettes, fountain pens. It also published a lot of very good writing. Margaret Atwood published “The Bog Man” in Playboy. Alex Haley interviewed Martin Luther King for them. Alice K. Turner, the magazine’s longtime fiction editor who died in 2015, was one of only a few female literary tastemakers of the twentieth century. For better or worse, Playboy’s literary height coincided with the rise of New Journalism, drawing into its net Norman Mailer and Gay Talese. The journalist Charles Taylor in 2002 described the contents of the 1968 Christmas Issue for Salon:

It’s December 1968 and you grab a mag at the local newsstand. The table of contents includes the following: A quartet of short stories by Alberto Moravia; a symposium on creativity with contributions from Truman Capote, Lawrence Durrell, James T. Farrell, Allen Ginsberg, Le Roi Jones, Arthur Miller, Henry Miller, Norman Podhoretz, Georges Simenon, Isaac Bashevis Singer, William Styron and John Updike; humor pieces from Jean Shepherd and Robert Morley; an article on pacifism in America by Norman Thomas; a piece on how machines will change our lives by Arthur C. Clarke; an essay on “the overheated image” by Marshall McLuhan; contributions from Eric Hoffer and Alan Watts; an article in defense of academic irresponsibility by Leslie Fiedler; a memoir of Hemingway by his son Patrick; Eldridge Cleaver interviewed by Nat Hentoff; a travel piece by the espionage novelist Len Deighton; and the first English translation of a poem by Goethe.

But as Taylor points out, most collectors covet the Christmas 1968 issue of Playboy because it contains naked photographs of Cynthia Myers, who would shortly appear in Valley of the Dolls.

Was Playboy good for America? The question feels exhausting. You can see the magazine from literally any analytic angle and find what you are looking for. Want to prove how pornography hurts women? Sure: Hefner called feminism his “natural enemy.” Want to show how hetero pornography supported and made mainstream gay liberation when America hated gays? Okay: In 1955 it published “The Crooked Man” by Charles Beaumont, a story about a dystopia where heterosexuality was taboo. In defense of his decision, Hefner wrote that persecuting homosexuality was “wrong.”

Perhaps the only true generalization there is to make about Hugh Hefner is that he is regularly given far too much credit for his role in American history. On Thursday, Julie Bindel wrote that Hefner “was responsible for turning porn into an industry.” He did not make pornography successful—his readers did. Meanwhile, the tweets proclaiming him a man of good literary deeds and bad sexual ones also miss the point: Hefner did not pen “Late Night.” David Foster Wallace did.

As we come together to bury Hugh Hefner, let us admit that his greatest legacy lies in the writing done about him by women. The greatest of these achievements is “A Bunny’s Tale” by Gloria Steinem, published May 1963 in Show magazine. Over eleven days spent working undercover at a Playboy club, Steinem put the lie to Hefner’s claims that he was the herald of a new sexual consciousness and showed how it was only offered up to men. She wrote of how she was tested for STIs by her employers, and told whom she may or may not date. She was expected to pay for her own false eyelashes. The wages were dismal.

In the early 1980s, Barbara Ehrenreich published The Hearts Of Men, American Dreams and the Flight From Commitment. It contained some of the best analysis of Playboy’s role in the so-called sexual revolution. “The magazine’s real message,” Ehrenrich wrote, “was not eroticism, but escape.” It offered men freedom “from the bondage of breadwinning. Sex—or Hefner’s Pepsi-clean version of it—was there to legitimize what was truly subversive about Playboy.” The nudity was not the central pillar of Playboy’s significance, she claimed. Instead, its message was about masculinity and the family unit: “every month, there was a Playmate to prove that a playboy didn’t have to be a husband to be a man.”

To these women’s writings we should add the multiple autobiographies of Holly Madison, some of them harrowing. We should add Coming Out Like A Pornstar, an extremely fine collection of essays by adult film performers, edited by the performer and writer Jiz Lee. We should add the many essays already published and the essays to come by people of all genders and sexual orientations who now live in a world without Hugh Hefner. Like a nude shot in the rolling gardens of the Playboy mansion, breasts obscured by foliage, we can at last see things in perspective.