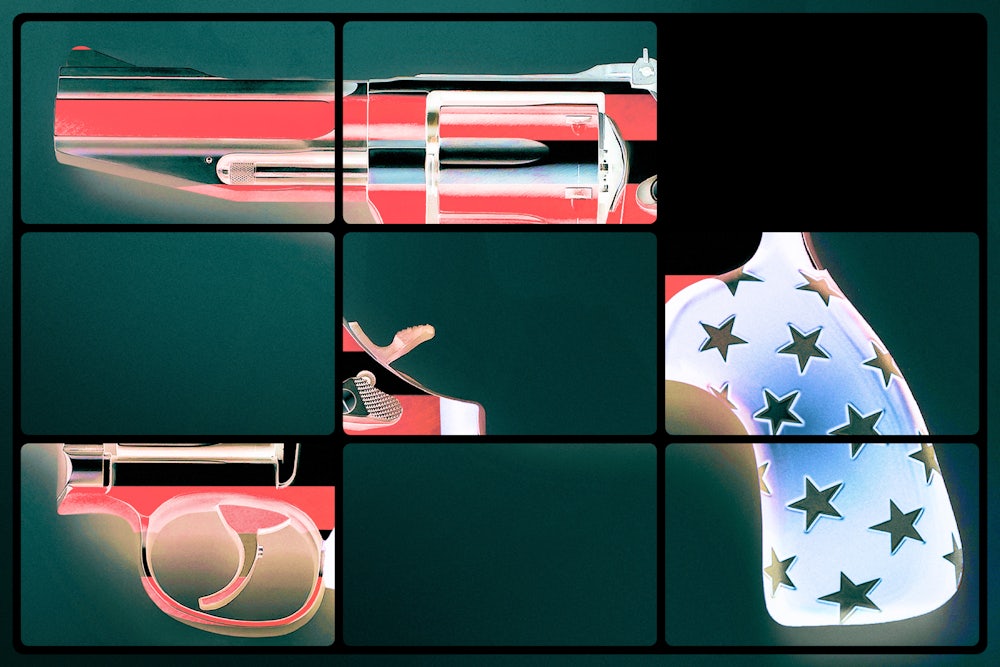

In 2012, a day after the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School, Gary Wills wrote an essay in The New York Review of Books called “Our Moloch,” a reference to the ancient Canaanite god whose worship entailed the sacrifice of children. “The gun is our Moloch,” Wills wrote. “It is an object of reverence,” one so dominant and pervasive that it “has the power to destroy the reasoning process.” Gun worship, Wills argued, prevents us from doing anything about the manifest link between the extraordinary number of guns in this country and the extraordinary number of gun fatalities that happen every year. And so we not only allow children to die, but also allow living children to be parted from parents and loved ones who have been killed by guns. These are the bloody offerings that demonstrate “our fealty, our bondage, to the great god Gun.”

“Our Moloch” is a document of cold fury, produced as the images from Newtown were still stamped on the author’s eyes. It is perhaps the most poetic example of what has become a polemical genre: an attempt, in the aftermath of yet another horrific mass shooting, to make sense of America’s unyielding devotion to guns. “Our Moloch” presents the gun cult as “the sign of a deeply degraded culture,” but it is mainly concerned with one aspect of that culture, a quasi-religious movement whose adherents are caught in its blinding spell. From this fanatic core a culture ripples out, in ever-widening circles of influence: the gun lobby, the Republican Party, the American government writ large.

This is a familiar liberal narrative to anyone who has followed the gun control debate. It is the substance of many inflamed op-eds that have greeted our latest sacrifice to Moloch, the 59 people who were mowed down in Las Vegas by a sniper in possession of an arsenal of guns, some of which were altered to behave like fully automatic weapons. To this narrative we could add a few data points that we have accumulated since Sandy Hook: that gun enthusiasts have expanded from a small minority into a powerful constituency, turning gun rights into an essential pillar of conservative political identity; that yearly gun production soared by 239 percent during the Obama administration, in response to apocalyptic warnings that he was coming for people’s guns and, more frightening still, their way of life; that gun sales tend to spike and gun laws tend to loosen after massacres like Newtown and Las Vegas, due to a similar fear of confiscation. The end result is this: persistent mass shootings, persistent gun deaths, persistent helplessness in the face of a problem that has no end in sight—the kind of helplessness that is so deep, so profound, that it leads us back to ancient wickedness for some way to comprehend it.

But if the Las Vegas shooting, for all its unprecedented carnage, felt familiar, this was not only because such shootings have become commonplace. It was also because the subsequent sense of helplessness—the sobering realization that we do not have the means to put an end to entrenched patterns of self-destruction—is now prevalent in many arenas of public life, from health care to police brutality. The great god Gun is now just one of a pantheon of deities—the great god Free Market, the great god Law and Order, the great god Patriotism—who demand their daily offerings and who confound the reasoning process. Together they form a totalizing belief system that increasingly has no overlap with the country’s other political belief systems. In this respect, the long-running gun control debate was not an idiosyncratic strain of American politics, but a precursor to Donald Trump’s America, where every debate breaks down on warring cultural lines and where there is virtually no expectation that things will get better. We can only hope they don’t get worse.

Just last week, Senate Republicans shelved an Obamacare repeal bill that would have uninsured tens of millions of people, caused health care costs to rise, and undercut bedrock insurance programs for the most vulnerable people in this country. Under pressure from constituents and activists, and facing a wave of negative press coverage, three Republican senators came out in opposition to the bill, which was enough to kill it. This could be seen as a victory for civil society, the free press, and a democracy that still has the power to punish lawmakers who make bad votes. But on the flip side, as New York’s Eric Levitz pointed out in a previous push to repeal Obamacare, we should be appalled that as many as 49 senators were willing to pass an enormously destructive bill for no other reason than to fulfill a cynical campaign promise to their tribe.

In reality, the health care fiasco shows just how fragile our democratic safeguards have become, how the fate of millions is dependent on the whim of a few individuals who are willing to buck factional loyalty, and how impotent most of us are when it comes to swaying this debate. It also shows that this was not really an argument about health care at all; it certainly was not about making health care better. It was a proxy fight for a larger cultural battle—against Barack Obama, against technocratic elites, against progressives—of which gun rights are an integral part.

The trends toward hyper-polarization and negative partisanship are only exacerbated by Donald Trump, who has a special gift for revving the engines of the culture war, pulling even issues like disaster relief into the cultural sphere. Less than two weeks ago, he trained his ire on African American football players who had refused to stand for the national anthem in protest of police brutality, sensing, correctly, that most Americans oppose this form of protest. The consensus view was that he badly erred in calling protesting athletes “sons of bitches” who should be fired. With (mostly black) players and (mostly white) team owners united in their opposition to Trump, polls show that a solid majority of Americans think Trump was in the wrong.

Still, a plurality of Americans believes athletes should not kneel during the anthem, including nine in ten Republicans. And all this clouds the original issue of police brutality against minorities, a subject on which Americans remain sorely divided, largely on racial lines. Meanwhile, the police killings continue, their frequency only matched by the exonerations that invariably follow.

These are just two examples that have occurred in the last 14 days. In each it is possible to observe the influence of a Moloch-like figure, a cultural totem that has outsized meaning for its acolytes, perhaps precisely because it is abhorrent to the unbelievers. It is impossible in these conditions to engage in a “reasoning process” between opposing camps that would allow the salient facts to prevail, such as the inhumanity of the GOP’s health care proposal and the inescapable reality that black Americans suffer far too many unjust deaths at the hands of law enforcement. There is seemingly no argument liberals can make that will lead to a conservative change of heart. The only certainty is that our ideological opponents will say that we are the ones who are suffering from a delusion, who are blinded by the biases that stem from our own fallen culture, our own foul gods.

Just think of what it would take to turn America into a country where people were not regularly killed by guns. The very first step would be to severely restrict the number and kinds of guns produced for consumers, which would require nothing less than a political miracle. The next step is even more daunting: confiscating or buying back a good portion of the hundreds of millions of guns already in existence, from owners who are predisposed to distrust the government and who view guns as a means to preserve their independence. The government would have to write sensitive, intelligent laws that curb not only the more spectacular incidents of gun violence, like mass shootings, but also the everyday gun violence that barely registers as background noise. This type of violence often occurs in cities, among minority communities, so these laws would have to be crafted in such a way that they don’t disproportionately affect minorities and put more of them in jail.

Every stage of this process is fraught with cultural pitfalls. Is the America of 2017 nimble enough, mature enough, unified enough, to negotiate that path? No, of course not. Will the America of 2027? When a person like Trump can be elected, there are few reasons to be optimistic. The prevalent feeling in the face of unchecked gun carnage is despair, and it’s hard to feel much else in the great drift of the Trump era. The president casually flirts with nuclear war, erodes the separation of powers, flouts the rule of law, enriches himself, and says nice things about the neo-Nazis marching through the streets. Meanwhile, everything is funneled back to the battle between us and them, and so every issue, every disagreement, has taken on the quality of the age-old gun control debate. The outrage reaches an ever-higher pitch, yet the damage just doesn’t stop.