If Northern California’s famous wineries could survive Prohibition, there’s no doubt they’ll make it through this year’s wildfires. That’s the attitude of Michael Honig, chairman of the Napa Valley Vintners trade association, who told New England Cable News this week that the 14 wineries damaged or destroyed by the ongoing blazes would not only rebuild, but come back stronger. “This is a short-term setback,” he said.

It may take some time, but other Californians will eventually adopt Honig’s determination to reconstruct the thousands of structures lost to the ongoing blazes, which are the deadliest and most destructive in state history. Real estate journalist and investor Brad Inman is sure of it. “As a journalist, [I’ve written] stories about post-disaster rebuilding in places like Oakland and San Francisco after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake; Los Angeles after the 1994 Northridge earthquake; and visited Phuket after the 2004 Tsunami in Thailand,” he wrote this week. “I was always struck by people’s fierce will to rebuild.” Not long after the historic Oakland hills firestorm in 1991 destroyed 3,500 homes, families started to put their neighborhood back together, Inman recalled. Eventually, they created an even better Oakland hills—one with higher property values and better public works.

This is an understandable response. People displaced by fires need new homes, of course, and naturally they would do it on the land they still own. And insurance policies usually provide the means to do so. But our planet is different today, as is our understanding of what constitutes smart, sustainable development. Wildfires are wreaking more havoc; California’s ten most destructive wildfires on record have all occurred in the last 30 years. That’s partly just because there’s more stuff to burn: more structures, more cars, more people. But it’s also because of human-caused climate change, which makes it more likely that wildfires burn longer and stronger.

So just as we grapple with questions about rebuilding in flood zones as the sea level rises, we must grapple with rebuilding in wildfire-prone zones. Is it sensible reconstructing an entire community that could just burn down again? Is it worth the public cost, and at the risk of more firefighters’ lives? If so, can we build in a way that decreases the risk of catastrophic damage?

These questions extend not just to those homes destroyed by the Northern California wildfires, but to developers across the country who are choosing to build in high-risk zones. Sixty percent of new homes built in the U.S. since 1990 have been constructed in areas that adjacent to fire-prone public lands, and this is forecasted to continue, according to an analysis by Montana-based Headwaters Economics. Kelly Pohl, a researcher at Headwaters, says now’s the time to pressure developers to halt this trend—or, at least, to start using smart land-use strategies to reduce risk.

“We have to honor and recognize that this has been a really tragic fire season for lots of communities across the country. We’re talking about real people with memories, communities, and experiences that have been severely impacted by these fires,” she said. “But people’s memories are short, and we have an opportunity to learn from this.”

Americans in general, and Republicans in particular, hold almost as much reverence for private property as they do for the inalienable rights granted by the Constitution. Dictating where and how people build their homes—or even questioning it—invites immediate backlash. But some conservatives feel that there should be a price, or standard, for people whose personal decisions are more likely to cost taxpayers. “Anybody ought to be able to live wherever they want to live,” former FEMA Administrator Michael D. Brown, now a prominent conservative radio host, told me after Hurricane Irma destroyed seawalls and flooded homes in Florida. “I’m just saying taxpayers shouldn’t have to subsidize your choice.”

And taxpayers across the country do subsidize decisions to build in wildfire-prone areas. The U.S. Forest Service increasingly spends more of its budget on firefighting—from 13 percent in 1995 to 50 percent in 2015, according to Curbed. According to a Headwaters analysis, wildfire protection and suppression annually costs the government approximately $3 billion, which is equal to half of President Donald Trump’s proposed budget for the entire Environmental Protection Agency.

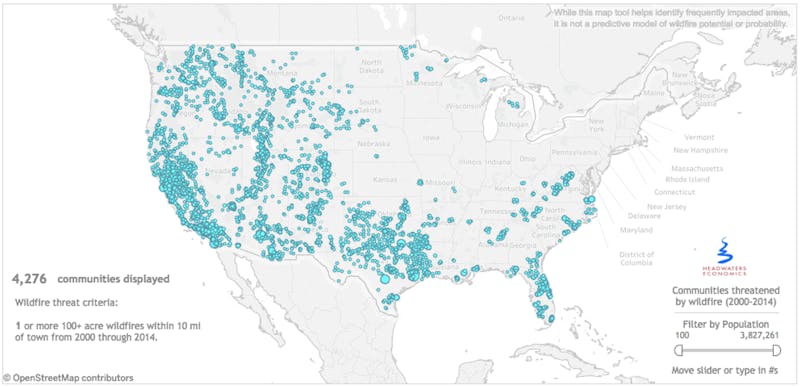

Those costs are expected to rise with climate change, and not just in places like California, Oregon, and Montana. Wildfires destroyed more than 100 homes in Tennessee last year, and this year in Florida, wildfires forced thousands to evacuate. More than 4,000 communities across the country are prone to 100-plus acre wildfires, according to Headwaters.

Property owners and communities also have to consider the monetary risk that wildfires pose to themselves, and not just the immediate damage caused by fire. “Communities bear long-term costs from wildfires over years because of lost business revenue, depreciating property value, and the long-term mental health consequences of living through a disaster like that,” Pohl said. The mental health impacts should not be understated. “Have you been around a wildfire before?” Pohl asked. “It’s dark as night. The sun is an orange ball. There’s ash and debris and embers raining down. It feels like the end of the world. It’s a life-altering experience.”

Still, the U.S. Forest Service expects population growth in wildfire-prone areas to continue. It estimates that there are approximately 45 million homes in the so-called “Wildland-Urban Interface”—the technical term for those in particularly vulnerable areas—and that the number will rise another 40 percent by 2030. WUI makes up 9 percent of the contiguous U.S., from Colorado’s Front Range to Southeast Texas to the Great Lakes states, and according to Headwaters, 84 percent of it remains undeveloped. So it’s unlikely and perhaps unreasonable that local governments would outright forbid development in all of these areas.

But there’s a lot that federal, state, and local governments can do to mitigate risk. “One of the strategies that we’re working with communities all over the country right now is developing land use regulations on how to reduce risk,” Pohl said, noting that a lot of the responsibility lies with state and local governments, which control zoning regulations. Communities at risk could require fire-resistant building materials like concrete, stone, glass, and brick; prohibit buildings on steep slopes, where fires move faster than on flat land; enforce a minimum distance between homes, since dense housing serves as better fuel for flames; require homeowners to plant only certain types of vegetation that doesn’t easily dry out and catch fire.

Federally, Trump could increase the Forest Service’s budget for wildfire prevention measures, like clearing dry brush and doing controlled burns. Trump could also create national codes and standards for building in the wildland-urban interface, as climate reporter Andy Revkin recommended in 2013 that President Barack Obama do. Those standards could be looser or tighter depending on level of hazard.

These questions, understandably, are not at the forefront of people’s minds in Northern California right now. Many residents are grieving, and many more are just beginning a difficult, years-long effort to rebuild what they lost. “This is my home. I’m going to come back without question,” Howard Lasker, a Santa Rosa resident who lost his home, told the Associated Press. “I have to rebuild. I want to rebuild.” That’s exactly why local and federal officials must consider these questions right now—to enact smart policy before the next massive wildfires strikes.