In the 1990s, my home state of Idaho gained a national reputation for being a hotbed of neo-Nazism. The driver of an SUV outfitted with iron-cross and swastika decals who tried to run my father’s car off the road was a neo-Nazi; the boy in my art class who painted those symbols onto a mural was the son of neo-Nazis. In the capital, Boise, the black history museum was periodically defaced with racist graffiti. When the city established an Anne Frank memorial in the early 2000s, it received the same treatment. White supremacists and their sympathizers were, for a time, a significant enough constituency that Idaho’s Republican politicians courted them during campaign seasons by expounding on Ruby Ridge and muttering darkly about black helicopters.

North of Boise, guarded by a crew of armed skinheads, was the Aryan Nations compound—a site the group’s leader, Richard Butler, called “the international headquarters of the White race.” Founded in the 1970s, the Aryan Nations grew out of Christian Identity theology, which held that only white people were descended from Adam and Eve. Throughout the 1990s, the group hosted annual white supremacist conferences; white power music festivals; and, most famously, flashy marches through the nearest town, Coeur d’Alene. Aryan Nations members were repeatedly linked to an assortment of domestic terrorist acts, including the bombing of the Coeur d’Alene courthouse, a triple homicide in Arkansas, and a shooting spree at a Jewish community center in Los Angeles.

While the Aryan Nations were particularly prominent in Idaho, plenty of groups and individuals outside the state’s borders shared similar beliefs. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the number of racist skinhead groups in the United States peaked during the late 1980s and early ’90s, a time when their members committed at least 35 murders. The ’90s also saw Timothy McVeigh lay waste to an Oklahoma City federal building, killing 168; the debut of the forum Stormfront, the first large-scale online network for white supremacists; and attempts by former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke to run for governor and U.S. Senate in Louisiana, receiving nearly 44 percent of the vote in the primary for the latter. It was, the SPLC reported, “a decade virtually unprecedented in the history of the American radical right.”

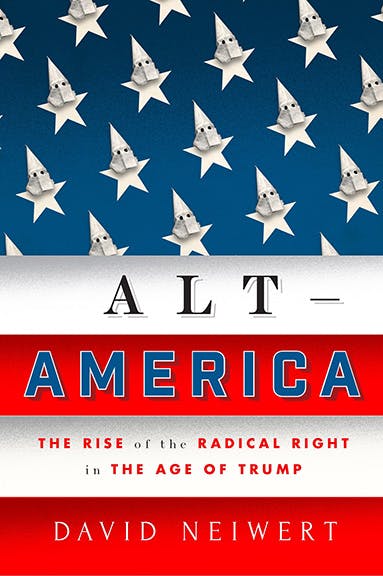

Journalist David Neiwert’s book Alt-America attempts to account for this period of far-right activity, which the media has largely failed to connect with more recent public displays of white nationalist sentiment. In August 2017, when members of white supremacist groups gathered to protest the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia, a man drove his car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer and injuring 19 others. To many commentators, this incident and Trump’s reaction to it—he saw “blame on both sides”—was proof that something in America had fundamentally shifted: With a president who refused to condemn even outright displays of hate, right-wing extremism was coming into the open. Photographs from that weekend of “enraged men carrying tiki torches and shouting racist and anti-Semitic slogans” signaled, the art critic Maurice Berger wrote in The New York Times, that white supremacy in America had “entered a new era.”

Yet Alt-America grimly reminds us that neo-Nazis, skinheads, Klansmen, Holocaust deniers, and various other stripes of white supremacist have held marches and rallies in America for many years, regardless of who sits in the Oval Office. The violent demonstration in Charlottesville and the murder of Heather Heyer were all the more horrifying precisely because they belong to a long history of far-right extremism. Tracing the ebbs and flows of this extremism in the United States over the last 20 years, Neiwert—who is also from Idaho—argues that white nationalist activity in the age of Trump is simply the latest flare-up of what he calls “Alt-America,” or the segment of the American population that has fed on conspiracy theories, racist misinformation, and deep distrust of federal institutions for decades.

The seeds of Alt-America were, in Neiwert’s telling, planted in the ’90s with the Patriot movement, a collection of paranoid, anti-government militias, whose membership often overlapped with that of the Aryan Nations and other white supremacist groups. Numerous Patriots declared themselves “sovereign citizens,” who believed the U.S. Constitution compromised the rights of free people, and who rejected the federal government as illegitimate and refused to recognize the authority of any official higher than the county sheriff. They vowed to avenge federal shootouts at Ruby Ridge and Waco, Texas, which they saw as proof of egregious government incursion into the lives of ordinary citizens. Inflamed by conspiracy theorists like the budding Alex Jones, Patriots fretted over an impending takeover of the country by the “New World Order,” a shadowy cabal of “globalists” bent on world domination.

At their height, during the mid-’90s, there were over 800 active Patriot groups, according to the SPLC’s estimates. Yet after the Oklahoma City bombing—carried out by one of their own—and the federal crackdown on domestic terrorism that followed, the movement began to crumble. Thousands of members were arrested for illegal arms possession or engaging in conspiracy to commit terrorism, and by 2000, the number of active Patriot groups had dropped to fewer than 200. The Patriots’ own delusions further cemented their fringe status: In the last months of 1999, they feverishly prepared for a Y2K apocalypse that failed to materialize; and after September 11, 2001, they insisted that the attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon had been false-flag operations—incidents covertly orchestrated by the government in order to create pretenses for instituting martial law and severely curtailing individual liberties.

The Patriot swell was, however, only the beginning of twenty-first-century American extremism. Neiwert shows that over the next two decades, particularly after Barack Obama took office, new far-right tendencies emerged, incensed by the election of America’s first black president (obviously a globalist) and whipped to greater heights of frenzy by right-wing media personalities. Pundits such as Sean Hannity and Glenn Beck fanned the flames of conspiracy by inviting Tea Party leaders and other far-right guests onto their shows and humoring a number of fringe theories, such as the idea that FEMA was operating a vast network of secret concentration camps across the United States. Among the new crop of extremists that flourished during this time were birthers, anti-immigrant border patrols, anti-Muslim groups sounding the alarm against “creeping sharia,” and a new wave of anti-government militias, such as the Oath Keepers and the Three Percent.

This reenergized right, Neiwert writes, was responsible for over 100 domestic terrorist acts between 2008 and 2015, including the murders of several police officers by militia members and the stockpiling of bombs and other weapons. Anti-government sentiment during the Obama years culminated with two standoffs between federal agents and the Bundys, a family of cattle ranchers with militia ties. The first of these began in 2014, when the Bureau of Land Management attempted to stop Cliven Bundy illegally grazing his cattle on federal land in Nevada. When bureau agents arrived at the ranch to round up and remove the cattle, Bundy called upon militias in the region to come to his aid. Around 100 armed men responded, and a tense confrontation ensued until the federal agents, fearing escalation, released the cattle. Two years later, in January 2016, Cliven’s son Ammon Bundy led a militia in the occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, demanding that the government turn over federal public land to state control. The standoff lasted a little over a month and ended with the surrender and arrest of the occupiers.

At the time of the Malheur occupation, the 2016 presidential primaries were also underway, and a new generation of young, internet-savvy white supremacists, who called themselves the “alt-right,” was gaining national attention. Represented by media-ready figureheads like Richard Spencer, the alt-right flourished on sites like 4chan, Breitbart, and the Daily Stormer, where they championed white identity through a mixture of inside jokes and memes and voiced zealous support for Donald Trump’s burgeoning campaign. According to Neiwert, the combination of militia support for the Bundy standoff and the rise of the alt-right online injected white nationalism with “new life, rewired for the twenty-first century.” Whereas earlier white supremacist groups had been based locally or else spread across secretive networks, the internet allowed alt-right trolls, KKK members, militiamen, and other extremists to form a “lethal union”—the segment of Trump’s base that Hillary Clinton infamously dubbed a “basket of deplorables.” It appeared that Alt-America was amassing the power to elect a president whose views substantially aligned with its own.

Neiwert excels at tracking not just the movement and growth of extremist organizations but also their internal rifts and sectarian divisions. For example, his account of the Bundy standoff in Nevada documents the rancorous squabbling that broke out between militia factions at the ranch. One conflict centered on the subject of Eric Holder, then Obama’s attorney general: Some militia members dismissed the idea he was planning to launch a drone strike on the ranch; others fervently insisted it would happen. “Paranoid rumors are not only common at gatherings of anti-government Patriots,” Neiwert writes, “they’re practically the entire raison d’être for the get-togethers in the first place.” Likewise, another section of Alt-America fastidiously tracks how the Three Percent militia fractured following a disagreement among its leaders over whether the group should devote its resources to forming an off-the-grid separatist community. When the idea was vetoed, its main proponent promptly absconded to the Idaho wilderness and named his splinter group, confusingly, the “III Percent Patriots.”

For those who study the right, this attention to detail is indispensable and, at times, darkly amusing. But Neiwert’s painstaking cataloging of these distinctions sometimes ends up undermining his overarching suggestion that far-right factions have come together in the age of Trump as a coherent political force. Ultimately, he depicts a far right that is deeply fragmented and often incompetent. By his account, these groups have rarely enjoyed a cozy relationship with one another, let alone with the majority of American conservatives. While right-wing extremists of all types undoubtedly congregate on some of the same internet forums, Neiwert offers little evidence that the various strains of Alt-America—rural sovereign-citizen militias, long-standing neo-Nazi and Klan chapters, and the new generation of college-educated alt-right media personalities—have begun building meaningful alliances with each other.

What Alt-America confirms is that despite their long and violent history, organized white supremacists have been, and still are, fringe groups with limited reach. While the alt-right enjoyed a burst of media attention during the 2016 presidential election, its world of obscure, irony-laced memes has largely failed to resonate offline. Furthermore, if what the far right has called its “largest rally in decades” amounted to no more than several hundred people with tiki torches winding their way through downtown Charlottesville, they are not doing well. For a sense of proportion, consider that a pro-refugee rally at the statehouse in Boise, Idaho—a city with a population of about 200,000 that is nearly 90 percent white—drew almost 1,000 people in November 2015.

Despite the energy the alt-right gained during the election, it also appears to be splintering in the wake of the deadly Charlottesville rally—or at least undergoing a serious internal reckoning. The rally was disowned by a number of prominent right-wing figures, such as former Breitbart staffer Milo Yiannopoulos and Gavin McInnes, founder of the “Western chauvinist” fraternity the Proud Boys. Journalist Angela Nagle, who has tracked the alt-right’s online evolution for years, wrote in August, “In all of my time observing the alt-right, I have never seen its adherents so uncertain, floundering, excuse-making, and on the back foot.” Since then, rather than taking up the mantle of vigilante violence, the majority of the alt-right’s adherents have retreated to the safety of their computer screens. When one of their “free speech” rallies in Boston was dwarfed by a counterprotest, the organizers announced that over 60 other rallies they had planned would instead “be conducted through online and other media.” And when Richard Spencer returned to Charlottesville in early October 2017, he joined a “group of about 40 or 50” for a demonstration that lasted ten minutes.

Even in these relatively small numbers, of course, white nationalists are able to cause real harm. Open displays of hate—cross-burnings, torchlit marches—are by their nature designed to shock and intimidate. But acts of aggression, and even instances of violence, are not the same as political power. No matter how delighted the alt-right may be to find its preferred candidate in the White House, it didn’t deliver the presidency to Trump. He was helped into office by an antiquated and undemocratic electoral college system, by loyal Republican voters, and by the flaws of the Clinton campaign, which spent more effort trying to capture a slice of the Republican base than appealing to disaffected voters in the Rust Belt.

Since the 1970s, the SPLC has monitored extremist groups across the nation and attempted to fight them through the law. It has scored multiple victories on this front, including the lawsuit that brought down the Aryan Nations. In 1998, Idaho residents Victoria Keenan and her son Jason were driving back from a wedding when their car backfired on a road near the Aryan Nations compound. Mistaking the sound for gunfire, armed guards at the compound chased and shot at the Keenans’ car with assault rifles and eventually ran it into a ditch. The Keenans were then held at gunpoint and beaten. Represented by the SPLC, they filed a civil suit and were awarded $6.3 million in damages in 2000, bankrupting and effectively ending the Aryan Nations.

This is to say that the SPLC (a group to which I have donated many times) serves an important function, and its methods for extinguishing the material resources of violent extremists remain formidable. But when the public focuses on the loudest and most obviously threatening displays of racial hatred, it can mean overlooking more insidious forms of racism that are woven into the fabric of everyday life. * In a surly column in The Nation titled “King of the Hate Business,” the late Alexander Cockburn skewered the SPLC’s frequent solicitations for donations, which tend to be tethered to ominous statistics showing a rise in the number of hate groups. As Cockburn noted, these purported surges of hate seem never-ending, even though, at the time of his writing, the organization held over $170 million in net assets and revenue that exceeded its expenses by more than $14 million.

Some of that money, Cockburn suggested, could be directed toward helping workers fired in a union drive, immigrants facing deportation, or those incarcerated in “the endless prisons and death rows across the South, disproportionately crammed with blacks and Hispanics.” (The SPLC does in fact run a variety of programs on immigrant justice, economic justice, and criminal justice reform). What he meant is that racial injustice is most often divorced from the spectacle of swastika-waving neo-Nazis and instead realized through more quotidian inequalities, such as residential and school segregation, the racial wealth gap, a broken criminal justice system, and the funneling of nonwhite workers into low-wage or precarious job markets. These conditions threaten the wellbeing and lives of millions, putting black Americans in particular at disproportionate risk of material hardship as well as diminished physical and mental health and life expectancy.

This is important to keep in mind as many prominent liberals continue to contrast Trump—whose overtly racist and xenophobic comments often resemble alt-right positions—with more restrained Republican politicians. Writers for publications such as The Atlantic and Mother Jones and celebrities such as Ellen DeGeneres have lately embraced George W. Bush—forgetting (or forgiving) his administration’s invasion of Iraq, mishandling of Hurricane Katrina, and series of tax cuts for the wealthy—simply because the Bush family has criticized Trump. So, too, have liberals praised Republican senators John McCain, Jeff Flake, and Bob Corker for their rebukes of the president’s extremist rhetoric. These remain the same legislators who have cut into the social safety net, crafted tax policies that redistribute wealth upward, and deprived millions of people of affordable health care. The political danger is less the alt-right than it is its established counterpart.

* An earlier version of this article incorrectly characterized the scope of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s work. The Southern Poverty Law Center runs a variety of programs on immigrant justice, economic justice, and criminal justice reform. The article has been updated. We regret the error.