Midway through Jean Raspail’s 1973 novel The Camp of the Saints, the French president asks his army to consider shooting refugees on sight: “I am asking every soldier and officer, every member of our police—asking them from the depths of my conscience and my soul—to weigh this monstrous mission for themselves, and to feel free either to accept or reject it.” Raspail makes clear that the president, bowing to liberal sentiment, should have never allowed the army a chance to object. As a result of its left-wing decadence and self-hatred, Europe fails to realize the threat it faces until the refugee hordes land and pillage.

Raspail’s enemy is the entire non-white world. It tramples monks and white saviors alike in its invasion of France. His refugees are nameless caricatures, with no inner lives. He ascribes to them an almost supernatural combination of obstinance and depravity. The smell of death is the first sign their rickety ships are about to land, because they dump their corpses in the sea. They are savages, led by a literal shit-eater, and they foist their poison dead upon the shores of Europe before their feet touch earth. It is allegedly one of Steve Bannon’s favorite books—and on the right, he is not alone.

“Raspail was ahead of his time in demonstrating that Western civilization had lost its sense of purpose and history—its ‘exceptionalism,’” Mackubin Thomas Owens wrote in a 2014 piece for National Review. A decade earlier, William F. Buckley Jr. called the book “a great novel” in the same publication and added, while musing over the plight of refugees, “What to do? Starve them? Shoot them? We don’t do that kind of thing—but what do we do when we run out of airplanes in which to send them back home?” There, he ended the column.

White nationalists have answered Buckley’s question. The Camp of the Saints is a veritable fixture on alt-right forums across the internet. It stars in Stormfront threads and appears on reading lists disseminated on 8chan’s /pol/ board. At VDARE, white nationalist writer Chris Roberts compared it to George Orwell’s 1984. The Camp of the Saints appears frequently on Reddit, in r/Europe and r/New_Right and r/DarkEnlightenment and r/The_Donald, where eager Trump fans even launched a live reading series. Matthew Heimbach, founder of the Traditionalist Worker’s Party, recommends the novel to his followers; so does Jared Taylor, founder of American Renaissance, which bills itself as “the internet’s premier race-realist site.” “The Camp of the Saints has never gone out of print, and has been translated into all major European languages—and yet the coverage of the European ‘migrant’ crisis goes on as if it had never been written,” Taylor complained in one piece.

“Of course, Raspail was denounced as a racist, and his emphasis on the white race can indeed be off-putting,” Owens wrote. “But the central issue of the novel is not race but culture and political principles.” At The American Conservative, Rod Dreher called The Camp of the Saints “a bad book, both aesthetically and morally,” but added, “his cultural diagnosis struck me as having more merit than I anticipated, given the book’s notorious reputation.” Dreher has since admitted the book is racist, but maintains that “there were, and are, also some important truths to be minded out of the narrative, especially when it comes to the way progressive ideology in the European establishment institutions (state, church, media, academia) disarms people in the face of a hostile and alien culture.” Recall that the “alien culture” of Raspail’s book murders and rapes, and only suffers from poverty because of its own moral depravity and stupidity.

Culture also appears frequently in Bannon’s rhetoric—he often speaks of the U.S. as a “civic society” whose identity would be diluted by immigration. Iowa Representative Steve King (R) has recommended the book in between rants about the decline of “Western civilization.” Admiration, or at least cautious respect, for The Camp of the Saints seems to be where conservative commentators and politicians align with white nationalists. It offers insight into the true nature of the right’s fear of immigration, and shows the extent to which that fear has been normalized.

The Camp of the Saints has long been influential in organized white supremacy. “In 2011, the book started to get really popular in white nationalist circles,” Ryan Lenz, a senior investigative reporter for the Southern Poverty Law Center, told me. He compared its influence to that of the infamous The Turner Diaries, which imagines a race war that obliterates all non-whites and Jews. “And the reason for this,” Lenz explained, “is that in the early teens—in 2010, 2011, 2012—the idea of white genocide became very popular in the white nationalist news.”

Raspail’s fear—that a weak West will be easy prey for the ravenous East and South—fits neatly into white nationalist rhetoric. “The premise of Camp of the Saints plays directly into that idea of white genocide,” Lenz continued. “It is the idea that through immigration, if it’s left unchecked, the racial character and content of a culture can be undermined to the point of oblivion.”

These sentiments are old and deeply rooted. When immigration is in the news, the extent to which these fears grip white Americans becomes clear. “Some argue that immigrants will take jobs,” said Alan Kraut, a professor of U.S. history at American University. “But throughout our history, there are those who argue that the experience and culture of immigrants will dilute American culture and politics.”

Karthick Ramakrishnan, a professor of public policy and political science at the University of California, Riverside, told me that “racism and cultural anxiety are long-running strands in American history when it comes to immigrants.”

“That started with anxiety about Catholics, and it’s taken on different guises as different types of immigrant populations come into the U.S.,” he continued, “but what you see in the 1970s is that there were these environmental and resource constraint arguments that were used to make anti-immigrant sentiment and anti-immigrant movements more mainstream.” Later, immigration restrictionists folded national security concerns into their rhetoric. After 9/11, Ramakrishnan noted, anti-immigration groups like Numbers USA and FAIR saw their membership rolls grow. (FAIR was founded by John Tanton, whose Social Contract Press publishes the softcover edition of Raspail’s novel.)

“What’s happened is that in order to expand the adherence to the cause, usually the movement has tried to latch on to other ideas to move beyond the hard core when it comes to the restrictionist movement,” he added. “But I think what you’re seeing now is that with Trump that hard core has actually expanded. People can talk in mainstream company about these concerns about culture and not be painted as as racist.”

Lenz said, “You know from the Ku Klux Klan in the ‘20s and ‘50s to the neo-Nazis in Skokie, Illinois to the alt-right marching on college campuses now, their central argument is that white Americans need to protect the European heritage in America because it is under assault and subject to systematic efforts to get rid of it. It’s ultimately how racists respond to social change.”

Raspail channels that response. “But don’t you ever ask yourself what something like this would mean? The mixture of races, and cultures, and lifestyles?” an elderly professor demands of a refugee-loving hippie early on in the book. “The different levels of ability, different standards of education. Why, it would mean the end of France as we know it, the end of the French as a nation.” The professor then shoots the hippie.

Evidence shows that most terrorist attacks in the U.S. are conducted by whites, not brown Muslims. It also shows that low-wage immigrants are not stealing jobs from their white counterparts. But Trump and his followers also insist that their immigration concerns reflect basic cultural realities. It has nothing to do with race, they say; immigrants just won’t assimilate. They’ll be violent, like the Salvadoran gang MS-13, or they’ll introduce anti-democratic ideas into the pristine temple of American public discourse. Deployed in the service of immigration restrictionism, the idea of a monolithic “Western culture” or “Western civilization” gains a particularly sinister dimension.

The cartoonish violence and garish racism of Camp of The Saints have prevented it from becoming a truly mainstream work. Its influence appears limited mostly to white nationalists, and to a handful of conservative commentators. But its basic premise—that Western culture is at risk from foreign incursion—extends beyond these circles and has become deeply embedded in restrictionist rhetoric.

The example of MS-13 is notable in this respect. The gang is undeniably violent, but its presence in the U.S. can’t be attributed to some nefarious immigration wave. The U.S. government itself bears some responsibility for its existence. Experts agree that the gang grew out of El Salvador’s vicious civil war—a war facilitated, in part, by the U.S. government’s decision to arm the right-wing Salvadoran government against left-wing militias. When death squads murdered Salvadorans, they did so with U.S. money and weapons. Now there is MS-13, and conservative rhetoric frames the gang as proof of a dangerous incoming horde rather than as the byproduct of U.S. intervention.

By inflating the threat of MS-13 and ignoring its real origins, restrictionists are better able to pretend that their policies serve national security. MS-13 isn’t a useful ploy just for Trump: Republican Ed Gillespie also featured the group in ads for his failed campaign for Virginia governor. For Attorney General Jeff Sessions, the group is a convenient excuse to expand the focus of the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces.

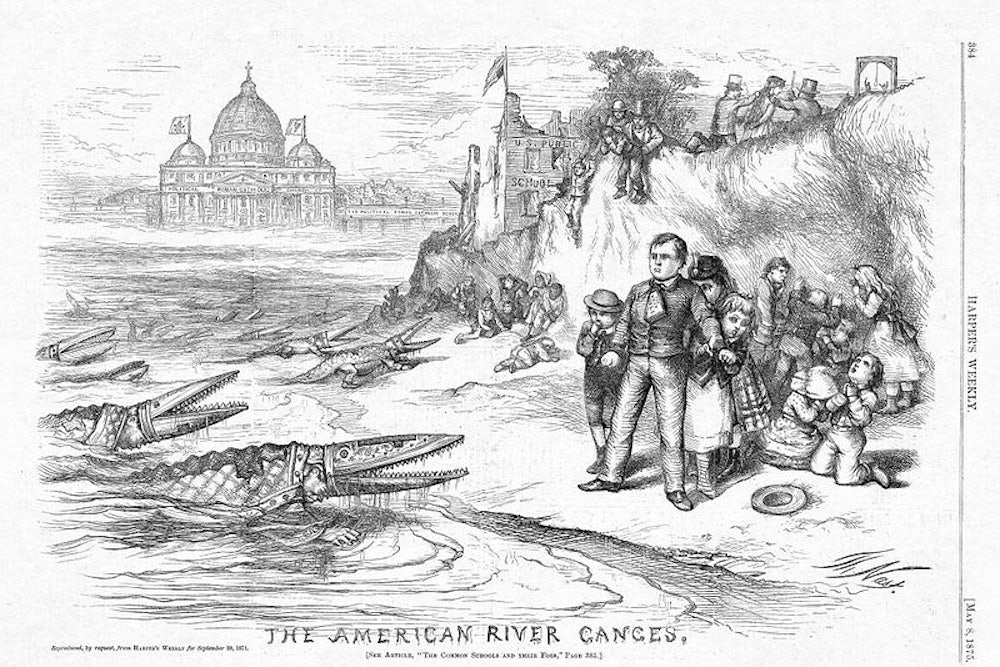

Muslim-Americans will recognize the tactics. Trump had barely taken office before he tried to ban incoming nationals from seven predominantly Muslim countries. The bans protected national security, the government argued. This did not persuade the courts, which understood the bans for what they were: a revival of the racial prejudices that have historically informed American immigration law, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Amidst all the fearmongering over religious extremism, it’s possible to hear whispers of older fears: The Italians are violent; the Chinese will never assimilate; Catholics want to place America under papal rule. The Anti-Defamation League reports that 83 percent of extremism-related murders in the U.S. are committed by white supremacists, and statistically, undocumented immigrants are no more prone to crime than any other demographic. But facts are usually not as persuasive as fear.

Wrote Raspail in 1993, “It is said that history does not repeat itself. That’s very foolish. The history of our planet is made up of successive voids and of the ruins that others have strewn about as they each had their turn, and that some have at times regenerated.” These are the truest lines he ever penned. We stumble over ruins, repeating past sins, but the sins aren’t the decadence or tolerance or pity that Raspail feared. The sins are fear and hatred.