“I’ll be honest with you,” said Gary Michael Hunt. “You never know when you go in there and turn on the faucet if you have water, or if you ain’t going to have no water.” Hunt, a former coal miner who lives in Martin County, Kentucky, said he has had reliability and safety issues with his drinking water for about 25 years—including water permeated by excessive amounts of disinfectant chemicals. “The water stinks. It’s cloudy-looking,” he explained. Hunt’s not alone: More than a thousand of his neighbors in Martin County regularly have to deal with creaky faucets that sometimes spew liquids of various scents and hues.

The county water board says these issues stem from old, busted-up water infrastructure and a “bleak” financial situation. To solve it, the board proposed raising water bills. That did not go well. At a fiscal-court meeting on January 11, Hunt stood up, used profanity, and shook a finger in the board’s direction. A state trooper approached Hunt, pushed him backward by the neck, and escorted him from the courtroom. Hunt was cited for disorderly conduct and has a February 26 court date.

“I would just like for him to say he’s sorry for choking me,” Hunt said. He’d like clean drinking water, too, but neither seem likely for now. A Kentucky State Police spokesperson confirmed that Hunt faces charges; when asked if it was common for officers to place hands on the necks of individuals during arrest, he refused to discuss the matter and hung up.

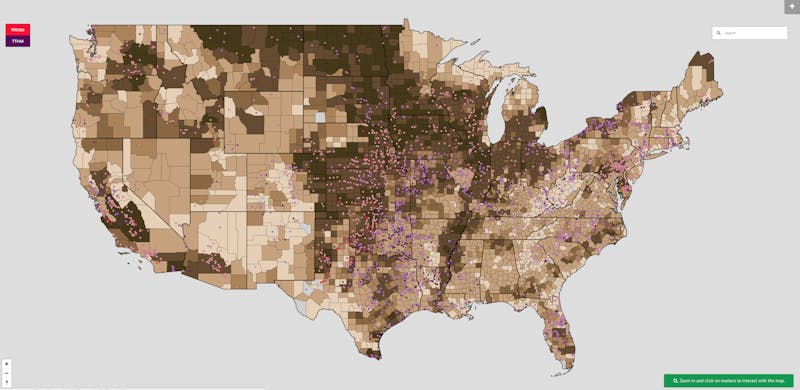

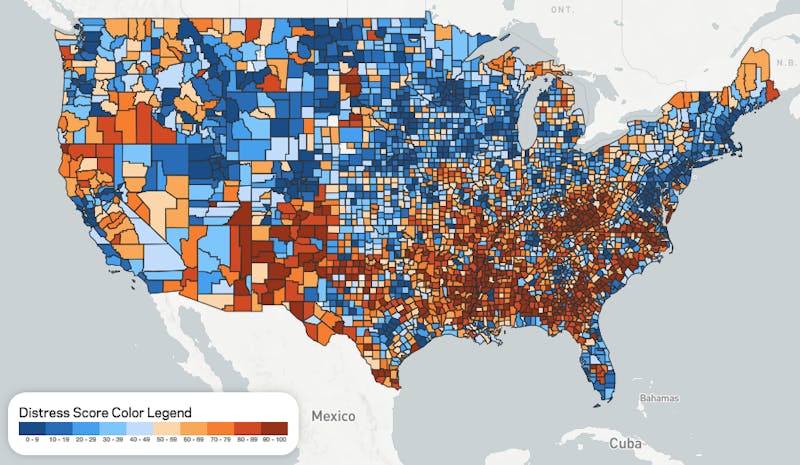

When people think of water crises, they tend to think of big cities like Flint, Michigan, or Cape Town, South Africa. These places understandably attract the most attention, because one faulty system in an urban area can affect vast numbers of people at once. But, in reality, most health-based violations of drinking-water standards occur outside of big cities, in places like Martin County: small, poor, out of the way. Of the 5,000 drinking-water systems that racked up health-based violations in 2015, more than 50 percent were systems that serve 500 people or fewer. In those small areas, who is going to raise hell except for the people affected and maybe the local paper?

Put all these systems together, however, and rural America’s drinking-water situation constitutes a crisis of a magnitude greater than Flint, or any individual city. From Appalachian Kentucky to the Texas borderlands, millions of rural Americans are subject to unhealthy and sometimes illegal levels of contaminants in their drinking water, whether from agriculture, or coal, or plain old bad pipes. And as the economic gap separating rural America from its urban and suburban counterparts continues to grow, this basic inequality is set to become more entrenched—and possibly more dangerous, as sickness seeps into rural America.

Often, the very industries that provide a community its economic backbone are what’s damaging or even poisoning its water supply. In Martin County and other communities across Appalachia, that industry is mining. “A lot of people in Kentucky actually get their water from wells that are sunk into flooded, abandoned mines,” explained Erik Olson, a policy analyst for the Natural Resource Defense Council. “That water quality is horrific because the mines are loaded with heavy metals.”

Other communities, from West Virginia to North Carolina, trace their water problems to the waste produced from burning coal, which is often stored in liquid ponds that have a tendency to spill and leak. In West Virginia, some say accidents affecting the water supply have become a fact of life. “Seems like whenever something happens, we just shrug our shoulders and go about our business,” wrote Dustin White, a self-described “11th generation Appalachian native” raised in Boone County who is now an organizer for the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. “Local media may talk about it for a day or two, then it just seems to disappear.”

Toxic water may disappear from the headlines, but not from the bodies of local residents. Some research links mountaintop-removal mining to carcinogens in local groundwater that can lead to cancer, heart disease, and birth defects, which means thousands of families, especially those who rely on well water, live with constant anxiety about long-term health problems. Unsafe water takes a kind of shorter-term psychic toll as well. Hannah Bowen, an 18-year-old student at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, has lived in Martin County her whole life and has suffered from severe acne. A common teenage problem, she thought—until she moved away for college and it cleared up. “Every time I visit home and use the water, I notice my face breaking out again,” she said. In towns with water issues, every illness seems mysterious, leaving most people with a kind of free-floating fear.

Large-scale agriculture is the contamination culprit in many other rural areas: Nitrogen-based fertilizer slides off of farmlands and into the nation’s freshwater systems. The tap water in Pretty Prairie, Kansas, for example, “has exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s legal limit” for nitrate for more than 20 years, the Environmental Working Group reported in 2017. As a result, the town’s 672 residents have imbibed carcinogens for decades. The Environmental Working Group reports, “Studies by the National Cancer Institute have found that drinking water with just 5 [parts per million] of nitrate increases the risk of colon, kidney, ovarian and bladder cancers.”

Agriculture’s unsavory side-effects also plague the Mississippi River Valley. Colin Wellenkamp, the executive director of the Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative, said that communities in Arkansas down to the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico face the most serious nitrate issues, due to bioaccumulation of the nutrients in their water source. (While most nutrient pollution is released farther north, contaminants tend to travel south, where they accumulate and sit near the mouth of the Gulf.) Often, water-treatment facilities are too old to adequately filter out the chemicals. “Some of my cities are facing serious infrastructure issues because that stuff’s been neglected for so long,” Wellenkamp said.

The West Coast isn’t spared, either. “In some parts of California, like the Central Valley, you see both a combination of water-scarcity and water-quality problems, because of over-pumping or because of drought,” Olson said. “They often, unfortunately, go hand in hand, so even if you have water, it’s not fit to drink.”

Farther south, colonias—which are unincorporated settlements near the Mexican border—in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico also frequently lack running water or sewer access. According to the Rural Community Assistance Partnership, approximately 30 percent of residents in colonias didn’t have safe drinking water in 2015. Mary Gonzales, a Texas state representative, said the problem is compounded by inadequate wastewater infrastructure for the 253 colonias in her district. “If you can’t flush your toilet and the septic system isn’t an adequate one, the raw sewage comes out onto the street,” she explained. “That’s literally what happens.” She added that current immigration rhetoric has complicated efforts to develop colonias, even though most of these communities are decades old and most residents are citizens.

Fixing rural water problems can be a costly prospect, but finding the money is often more a matter of political will. In Texas, one colonia needs $32 million to build basic wastewater infrastructure, which Gonzalez says is not an insurmountable sum. Nevertheless, help has not been forthcoming. In 2017, Texas Governor Greg Abbott used the line-item veto to defund the state’s Colonia Initiatives Program. The state legislature also failed to renew the Economically Distressed Areas Program, which provided funding for infrastructure development. Gonzalez introduced a House Joint Resolution that would have created a constitutional amendment to fund the program through joint-obligation bonds. The bill failed.

“When I’m advocating funding for colonias, sometimes people don’t even know there are thousands of communities who don’t even have running water,” Gonzales added. “These communities have been invisible for a long time.” Colonias have long been subject to environmental injustice, but the rest of rural America’s water problems are largely invisible, too—not least to the government bodies responsible for solving them.

A few months after President Donald Trump’s inauguration, Kentuckians from Martin County were dealing with contamination—but, they told NPR, they were hopeful for new federal spending that could help rebuild their water systems and their trust in government. Their hopes are echoed in other suffering communities. Many of the contamination problems facing rural America can be traced to old, broken, unreliable infrastructure like leaky pipes, clunky filtration systems, and backed-up sewers. Trump, of course, has promised to fix America’s aging infrastructure: His plan is set to be released Monday.

If Trump really wants to help rural America, he’d have to confront two facts. The first is that white, blue-collar workers aren’t the only rural Americans who need assistance. Immigrant and Latino communities are also at the front lines of this crisis. The second is that rural water travails can’t be solved without public funding: new public funding. “If you’re going to put out a $200 billion infrastructure plan, and the $200 billion is coming from cuts or elimination of other domestic programs we depend on, it’s not going to help anybody,” Wellenkamp said.

Wellenkamp fears that Trump will choose to zero out community-development block grants, or water-pollution-control grant programs, in order to fund his bill. That fear makes sense: In 2017, Trump introduced a budget proposal that would entirely defund the USDA’s water and wastewater loan and grant program. Though his administration later rescinded that proposal, it indicated an apparent lack of interest in or familiarity with the program’s work.

And though Trump’s much-vaunted infrastructure proposal will reportedly set aside $50 billion for rural development, a leaked draft of the forthcoming plan makes clear that it may be nothing more than a boon for backers of privatization. “The Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) will be open for business for private firms to both manage and repair water infrastructure at taxpayer’s expense,” Michelle Chen recently explained at The Nation. “In addition, a credit scheme under the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act would provide more opportunity to private investors, by eliminating existing requirements that WIFIA funds be used for ‘Community Water Systems.’” The private sector, with its success strictly tied to profit-making, should not be involved in utilities at all. But certainly when public water money doesn’t even require those private water businesses to use it for, well, community water systems, then the chances those systems will improve is close to nil.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, The Washington Post has reported that the White House’s business-friendly infrastructure policy is being guided by a group of outside investors led by one of Trump’s billionaire friends, the developer Richard LeFrak. This is consistent with the Trump administration’s other business-policy priorities, like the Department of Labor’s proposed tip-pooling rule, which would allow restaurant owners to plunder their workers’ tips because owners know best how to distribute that money: In other words, Trump’s definition of economic progress is to grow the bank accounts of wealthy interests on the backs of everyday Americans and, yes, let it trickle down. Given that there isn’t much profit in running water to sparsely populated, low-income areas—indeed, water boards in rural communities are already raising rates to try to make ends meet—it’s unclear how blindly funding the private sector would incentivize the massive rebuilding projects these communities desperately need. Why give out tips or vast government checks when you can “reinvest” in yourself?

It’s only too easy to doubt Trump’s commitment to clean water. In addition to the above, the administration is openly hostile to the EPA, a stance that presents still more obstacles to drinkable water, and it at one point declared war on the USDA’s water-infrastructure funds, which advocates aren’t convinced the administration has really abandoned. “It would not stun me if they tried to take another crack at cutting substantially or even eliminating that funding,” Olson said. “It’s kind of ironic that the administration that purportedly wants to protect rural citizens has proposed eliminating one of the most important programs that helps rural communities have safe water.”

America’s failure to provide basic necessities to its rural citizens punches significant holes in the exceptionalist narrative favored by the Trump administration. It’s also a potentially life-threatening oversight. Rural Americans are already disproportionately more likely to die from cancer. Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention attribute the trend to a number of factors, including heavy tobacco use and obesity. But rural Americans also have to contend with inadequate public-health infrastructure: They’re more likely to be uninsured, and rural hospitals and community health centers are closing at a steady clip. This leaves rural communities ill-equipped to cope with the consequences of drinking contaminated water—assuming they can access water at all.

If water systems are not modernized soon, the changing climate will ensure yet more contamination, therefore increasing these disparities. A study published in the journal Science last year found that nutrient pollution flowing into the Mississippi River will likely increase as the climate changes, even if farmers don’t increase the amount of fertilizer they’re using. That’s because global warming is expected to cause more extreme storms and intense precipitation in the Midwest and Great Lakes, including the upper Mississippi Atchafalaya River Basin. In other areas of the United States, climate change is expected to cause more intense droughts and therefore more water-supply challenges. Those places include the rural communities in California’s Central Valley and south Texas.

Rural communities face a true nightmare scenario, and help isn’t on the way. These sparsely populated and sometimes deeply isolated towns and counties are already gripping the threads of an unravelling social safety net. Though rural America is making some economic gains, it still drags behind urban centers, and the gap is only expected to widen under Trump. But future administrations could change this narrative if they have the political will. The solution is massive public investment in failing infrastructure. Not only would this resolve a serious public-health crisis, it would also create jobs: You can’t fix rural America’s water without workers. Those jobs could even be folded into a federal-jobs guarantee, providing families with income while ensuring them access to safe drinking water and wastewater systems. Finally, a universal expansion of U.S. health care would resolve the insufficiencies of a privatized system and allow rural people to seek treatment for the physical consequences of drinking dirty water.

Those solutions won’t come from the Trump administration. In fact, individuals in both parties may balk at such a significant expansion of government. But it is the responsibility of government to protect the common good, and the state of rural water systems proves that this is a responsibility state and federal governments have refused to take up for far too long.