The Trump administration is delivering on its promise of financial deregulation. Mick Mulvaney has eroded the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau since being installed as acting director in November. The agency’s new strategic plan says it will “fulfill the Bureau’s statutory responsibilities, but go no further.” In practice this has meant freezing or dropping investigations against miscreant financial institutions like Wells Fargo and Equifax; delaying new rules regulating high-cost payday loans; preventing enforcement personnel to collect data on wrongdoing; and generally doing more to protect lenders than consumers.

The light touch extends beyond the CFPB. The Justice Department has thrown out “guidance documents” that dictate when to prosecute companies accused of misconduct; the effect will be to limit enforcement actions. The Securities and Exchange Commission doesn’t even publicize its weak attempts at punishment, burying announcements of fines in legal documents. Trump’s new choices for the Federal Reserve want to weaken rules on leverage that even many conservatives support. And a bill moving through the Senate with enough bipartisan support to beat a filibuster would represent one of the first statutory rollbacks of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law.

The Trump administration insists this financial deregulation will relieve costs from businesses and jumpstart the economy. But it’s clear where this laissez-faire approach leads: Without a cop looking over their shoulder, banks take more risks, increasing the danger of another crash. That theory has been surprisingly understudied in the academic literature, but a new working paper from the International Monetary Fund provides empirical support for the idea that large-scale deregulation generates financial crisis.

The report slipped by after its release last month without much notoriety. But it comes from an organization without a tradition of left-wing activism. It also adds context to what the Trump administration’s forays into financial deregulation may cause. This is what the prelude to a financial crisis looks like, historically speaking.

The paper by economist Jihad Dagher looks at ten financial crises going back 300 years, from a 1720 stock market crash in England to the Great Recession. The crises come from across the developed world: Japan, South Korea, England, Ireland, Spain, Sweden, and the U.S. Instead of focusing on the economics of the collapses, Dagher investigates the political economy: What was happening within governments that created the conditions for catastrophe?

Dagher finds a consistent pattern of what he calls “pro-cyclical” regulatory policies. You can think of it as a kind of pendulum: Deregulation coincides with a financial boom that inevitably busts, then a new government comes in and re-regulates the financial system. This pattern holds for all ten crises, with deregulation accelerating in the five years preceding the crisis in nine of the ten examples. The pendulum speeds up right before the calamity, and only then begins to swing in the other direction.

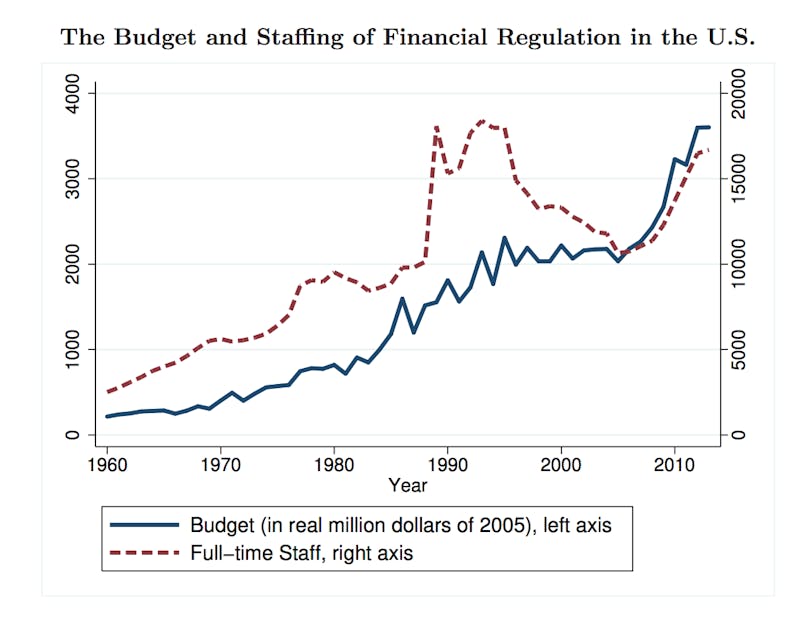

Governments in these various countries amplified the boom through weakening existing regulations and refusing to enforce violations of the rules. Dagher even pinpoints this in charts, showing staffing levels at bank regulators in the U.S. dropping during booms and increasing after busts.

For example, the dot-com boom of the late 1990s occurred during a series of deregulations in the securities industry, in particular several pieces of legislation that prevented so-called “frivolous” securities lawsuits against companies in state and federal court. This establishes a symbiotic relationship between deregulation and unsustainable run-ups in systemic risk. Similarly, Japan, South Korea, and Sweden “lifted banking regulations that were present for decades” in the prelude to the crash.

Dagher also finds that as bubbles inflated, governments worked with bankers and large companies to provide air for that bubble, by subsidizing the expansion of credit and boosting asset prices. This happened through government policies to feed booms and through close relationships between politicians and financiers, leading to episodes of corruption.

Ireland’s extreme tax cuts for home sales and property ownership in the 2000s encouraged a boom that led to a bust. Japan’s government introduced new lending instruments and increased bailout assistance during a time when stock market and land prices rose over 200 percent between 1985 and 1990. Even back in 1720, the South Sea Company bribed politicians to take over handling of government debt, creating a speculative bubble in its stock that popped. Most politicians were invested in the company in some form, leaving no incentive to put reins on the runaway speculation.

These crashes all led to reforms, with a new government sweeping in on promises to crack down on bankers. Most of the reforms involved total overhauls of the existing financial regulatory framework, with new institutions to supervise lenders; think of the Securities and Exchange Commission and deposit insurance after the Depression, or the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and its accounting crackdowns after the dot-com bust, or the CFPB today. But these have proven fragile historically, with post-crisis regulations not always surviving another boom. “Over time, the interest in financial regulation wanes, allowing the latter to decay and for regulators to be captured by concentrated private interests,” Dagher writes.

That deregulation increases risks to the financial system sounds like common sense. However, Dagher explains, “What makes this paper particularly timely is the high likelihood that the U.S. is on the verge of entering a period of deregulation.”

You could see the report as a warning of the potential horrors to come from the recurrence of historical events. We too often look at financial institutions as the cause of crashes, and of course they play a role. But the relationship between politics and financial system performance needs much more scrutiny. “Preventing the next crisis involves more than just an understanding of how the existing regulations failed, but also why they failed,” Dagher writes.

Nobody can say with specificity how Trump-era bank deregulation might lead to a crisis. But the IMF paper certainly shows that the environment Trump is creating matches the environment in countries before their financial systems blew up. If history is destined to repeat itself, then the recession that many fear could be around the corner.