“Speculation” has meant close, contemplative attention to a matter since the fourteenth century. In the negative sense of conjecture, the sixteenth century. In the sense of gambling on markets, the eighteenth. Since the police identified Nasim Najafi Aghdam as the woman who shot three people and then herself at YouTube’s San Bruno, California, offices on Tuesday, the court of speculation has been open.

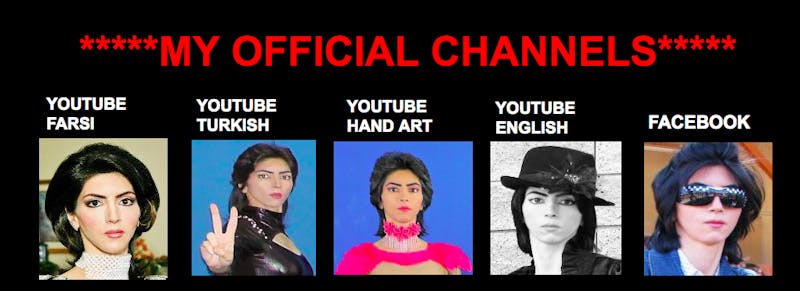

Aghdam had a significant presence on the internet, and that presence had a very distinctive look and feel. What appears to be her personal website—http://nasimesabz.com/—directs readers to Farsi, Turkish, and English-language YouTube channels, all of which have been disabled, as well as a now-unavailable Facebook page. She maintained Farsi and English Instagram accounts, and a Telegram channel. Those accounts are easily shut down by the service providers she used, including the one she literally shot at, but a personal website is harder to destroy.

Her post-mortem internet presence gives rise to many questions. What motivated her to post these videos and to style them the way she did? More importantly, what motivated her to shoot people and then to end her life? Given the target of her attack, those questions would seem to be inextricably linked. They facilitate a third question: whether it is appropriate to analyze a violent and possibly unwell person’s social media content with the tools of criticism. This question feels more urgent when that content looks like art.

Aghdam made videos about veganism and workouts. She also posted music videos, in which she danced in trendy but offbeat outfits against computer-generated imagery. By putting this content online, Aghdam was engaging in a kind of speculation, hoping for a response that hinges on various types of capital: social capital, in the form of likes and subscriptions and so on, and financial capital, in the form of monetization.

On her personal website, Aghdam complained about censorship by YouTube, specifically its “demonetization” policy barring small channels from making money, which was implemented earlier this year. Aghdam’s brother told KGTV that “she had a problem with YouTube.” She had other complaints about YouTube’s algorithm. “There is no free speech in real world & you will be suppressed for telling the truth that is not supported by the system,” she wrote at her homepage. “Videos of targeted users are filtered & merely relegated, so that people can hardly see their videos!”

These statements have led to suspicions that Aghdam’s violent crime was motivated by resentment towards the platforms on which she posted her content. But the content is also of interest on its own terms.

Young people online often refer to their “aesthetic,” using an updated definition of that concept to describe a sense of self that is communicated through their posts. The aesthetic is determined by pictures of the users themselves, as well as images from other sources. It is curatorial in nature—a way for people to shape and explore their identity through the world of imagery.

Aghdam’s “aesthetic” is striking. First, she was a very conventionally beautiful young woman, with strong eyebrows and a symmetrical face and a thin body. But her haircut was feathered and short, almost retro, and she dressed in strange outfits, wearing a camouflage-print bodysuit in one video, a blonde wig in another. In the background, Aghdam often used video footage of animals like cows and chickens and rabbits.

Her videos strongly resemble the field of contemporary art that recycles and reworks the visual vocabulary of the pre-broadband internet. This field includes the wider bracket of “net art,” which has been rumbling since at least 1994, and the later “post-internet” artists whose work engages on- and offline with the artifacts and language of digital culture.

Aghdam’s personal website was put together very simply, which you can see if you view its source code through your browser. It harks back to a time when most amateur internet users coded their own pages using html, rather than the platform-based language of Wordpress or SquareSpace “flat” design that we are familiar with now.

Aghdam’s engagement with that style seems to have been authentic, or non-ironic. Although many users across the world are, of course, still using that style in a non-ironic way, to other users it has become an “aesthetic,” a throwback look that self-consciously parodies and comments upon the way we used to be online.

Perhaps the most widely known artist to work this way is Petra Cortright, who now paints but whose ‘00s videos of herself doing nothing, overlaid with old-fashioned digital animation, were the subject of critical acclaim. This genre has many forms, as a good ArtNet piece on “influencer art” detailed last year.

That piece pointed to Awol Erizku’s Instagram portrait of Beyoncé pregnant with twins, which was a huge internet event. The blue background behind Beyoncé resembles the kind of blank screen that digital artists use when they want to replace it with other images. Aghdam used exactly that shade of blue as her background in many of her pictures. Presumably, this is also the background that she overlaid with videos of chickens and rabbits.

Intention is an old problem in art criticism, and a fruitful one. Critics and audiences have always been interested in the difference between an artist who seems to “mean” what they say, and one who is subverting that meaning. Does Cortright “mean” her videos, and if not, what makes them different from the “authentic” material created by Nasim Aghdam?

When Aghdam speculated on the market, she threw her videos into an arena structured by corporate giants. The media in turn is speculating about what that failed gamble did to her mental health. But images and videos go through a different kind of speculative process, one in which they are, in the original sense of the word, observed, looked into. And interpreting images on the internet is, as many artists have taken as their very premise, a jagged and unstable project. The link between creator, internet image, and viewer is so mediated—by form, by corporation, by capital—that there is no “authentic” path for the image to be mapped. What remains is the “aesthetic,” alone, and with it a mystery.