A young sperm whale, the largest toothed predator on Earth and an endangered species, washed up on the beach in southeastern Spain in February. Wanting to know what killed it, scientists brought the cetacean’s 13,000-pound body to a lab for a necropsy. They sliced into its blubber, and were shocked at what they discovered: 64 pounds of plastic throughout the stomach and intestines. This trash had caused the severe infection that took the whale’s life.

Scientists across the globe are increasingly finding wildlife that has been killed after ingesting or becoming entangled in plastic. Ninety percent of sea birds, for example, have been found to have plastic in their bellies. And the problem is only getting worse: The estimated 19 billion pounds of plastic that ends up in the ocean every year is expected to double by 2025. These plastics will not only kill more animals; they’ll decimate coral reefs, and damage human health as microplastics enter the food chain. They’ll create more and bigger dead zones where nothing can live, harm biodiversity, and change ecosystems. There will likely be additional, unknown impacts; researchers have only been studying ocean plastics for less than two decades.

This threat demands the type of aggressive action that only certain groups and countries are taking. After the dead sperm whale was discovered in Spain, the government launched a widespread awareness and cleanup campaign. Canada is using its presidency of the G-7 this year to push for international action on plastic pollution. In America, nearly 2,000 restaurants and organizations have banned straws or implemented a straws-only-upon-request policy, according to a July report in The Washington Post.

But banning straws—or plastic bags, or take-out containers—is not enough to solve the scourge of ocean plastics. In fact, no single country can make a significant enough impact to solve it before some of the impacts become irreversible. Like human-caused climate change, ocean plastic pollution is a huge and growing problem that demands a similarly ambitious solution. That’s why it should be approached in the same way: with an international agreement that imposes binding pollution reduction targets for every country, relative to their contribution to the problem. In other words, the plastics crisis needs its own Paris climate accord—and soon.

Last month, I was invited to a pre-screening of the final episode of BBC’s Blue Planet II at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. The invitation included the promise of an open bar. A few glasses of wine combined with high-definition shots of bright coral and bizarre fish—not to mention the soothing narration of famous naturalist David Attenborough—sounded like a good Wednesday night to me. I accepted.

But the final episode of Blue Planet II was not about the wonders of undersea life. It was about the vast damage humans are doing to the ocean. In one scene, a scientist comes upon the bloody carcass of an Albatross chick whose stomach was punctured by a toothpick. “Something as small as that has managed to kill the bird,” she said. “It’s really sad to see.” Later, the episode documented the story of a baby dolphin, discovered dead after drinking her own mother’s milk. Her milk, researchers found, was contaminated with microplastics.

Though the episode painted a dire picture, Attenborough was unflinching in his optimism. With enough effort, he said to the camera, we can rid the ocean of plastics: “The future of all life now depends on us.” At the end of the episode, the audience—including Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, who was sitting in front of me—stood in applause. But as the emotional glow of free Prosecco faded, I realized I was unclear about what, exactly, Attenborough wanted “us” to do.

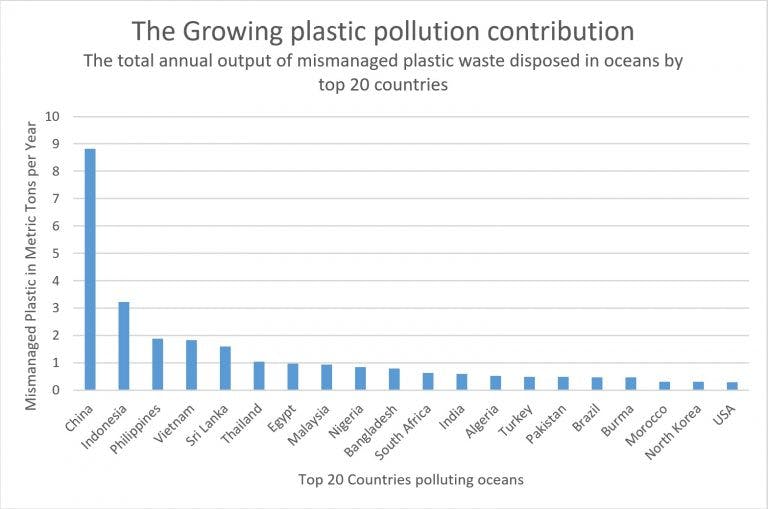

“Us”—Americans, at least—aren’t contributing significantly to the ocean plastics problem. Though our consumption of plastics is much higher than other countries, we have a much more rigorous approach to recycling and disposing of trash safely. Most of the plastic in the ocean comes from countries with less sophisticated waste management policies. According to a June 2017 study in the journal Nature, 86 percent of the plastic in the ocean comes from Asian rivers.

Asia is not, however, disproportionately affected by the impacts of plastic pollution. The majority of garbage put into the ocean ends up beyond national boundaries, in the infamous swirling “garbage patches” in oceanic gyres. In March, scientists published evidence that one of these whirls of trash—the Great Pacific Garbage Patch—contains about 80,000 tons of plastic, 16 times larger than previously thought. And as larger plastics linger in the water, they break down into microplastics that scientists are now finding everywhere: in fish, fertilizers, table salt, and in 93 percent of bottled water.

Because of the borderless nature of ocean plastics, scientists and activists are increasingly advocating for a global solution. “The time has come for a meaningful international agreement—one with clearly defined waste reduction targets and a solid foundation to provide all nations with the resources necessary for local reductions to be possible,” seven researchers argued in the pages of the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in September. That agreement could take several different forms, as environmental lawyer Linda Nowlan wrote in February:

One based on the Montreal Protocol—widely regarded as one of the world’s most successful environmental agreements—would impose caps on plastics production and trade bans.

Another points to the climate treaty, with countries setting a binding plastics goal and then developing national action plans.

Alternatively, others call for an agreement that institutes a waste hierarchy, where plastics are first reduced, then reused, re-purposed and finally recycled, and creates a global fund to help pay for better waste management practices and infrastructure.

The main challenge is that, like climate change, ending plastic pollution means stemming fossil fuels: “4 to 8 percent of oil is used to produce raw plastic,” the seven researchers noted. (In addition to crude oil, plastics are made from coal and natural gas.) And developing countries can be reluctant to discourage the companies powering their developing economies. But that’s where developed countries like the U.S. can help—by offering incentives and other financial help to those countries.

Steps are being taken toward a global agreement, but they’re paltry at best. In December, nearly 200 countries including the U.S., China, and India signed a United Nations resolution to eliminate ocean plastic pollution. A draft of the resolution had included legally binding, specific pollution reduction targets, but the U.S. reportedly led the way on rejecting that draft (China and India refused to sign the draft, too). So the final agreement merely calls for working toward the creation of binding targets. That seems unlikely to occur as long as the U.S. is led by President Donald Trump.

In the meantime, anti-plastic campaigns can make a small difference. Efforts to ban plastic straws and bags, for example, can raise awareness and change behavior over time. But these campaigns generally take place in the developed countries that aren’t contributing to the bulk of the problem. Engaging developing countries, through financial incentives and binding targets, is the only way to stem the flow of plastics into the oceans. Like Attenborough said, the plastics crisis is entirely within humans’ power to solve, but only if we do it together.