“This is really evil,” Professor Stan Glantz said after I sent him an article about the Environmental Protection Agency’s new science policy. Unveiled by EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt on Tuesday, the policy is a purported effort to improve transparency, but has the effect of radically restricting what science the agency can use to create public health regulations. The rule prohibits the EPA from using scientific research that includes confidential data about its human subjects, effectively rejecting much of the research showing how pollutants damage public health.

The EPA’s new policy reminds Glantz of the years he spent fighting the tobacco industry, which waged a decades-long campaign to suppress scientific evidence on the dangers of secondhand smoke. “This thing that Pruitt did is what tobacco and energy industries have been pushing for along time,” he said. “It’s not new. Pruitt is just the first one willing to go this far.”

Glantz, now a professor of tobacco control at the University of California San Francisco, was among the first scientists in America to publicly warn about those dangers. In the 1980s, he was met with some skepticism from the public and the tobacco industry, which denied the validity of his research. In the 2014 documentary Merchants of Doubt, a relatively young-looking Glantz is shown arguing with a TV host who refuses to believe his four-pack-a-day habit is bad for his or others’ health. “I smoke at my job every night, I’m not hurting anyone,” the host says. “That’s bullshit,” Glantz calmly replies, sparking outrage from the studio audience.

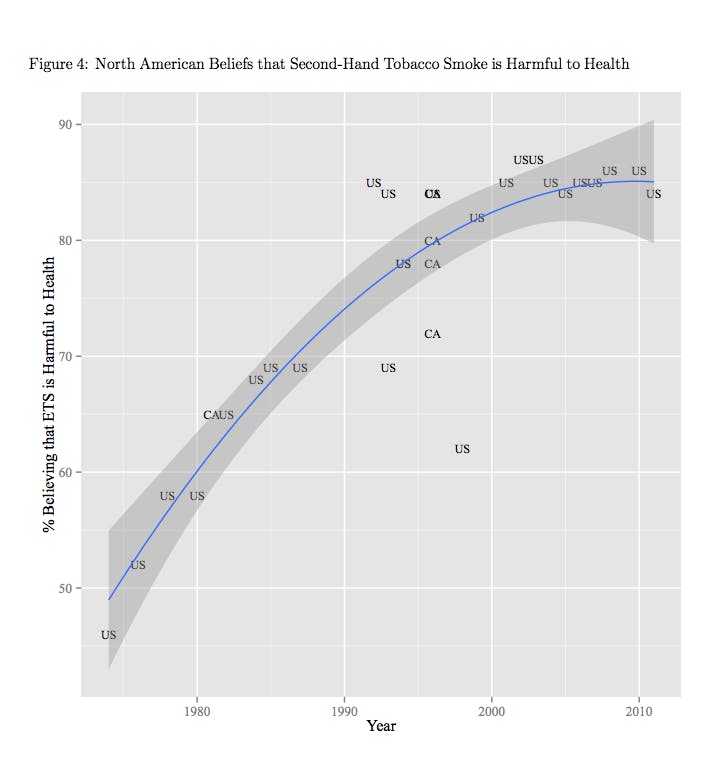

As years passed and more studies were published, public opinion began to shift. From 1994 to 1997, the percentage of people who believed secondhand smoke was “very harmful” jumped by nearly 20 percent. But tobacco companies continued to deny the evidence. Then, in 1995, Glantz and other researchers unearthed documents showing that the tobacco industry had known for 30 years that nicotine was addictive and smoking caused cancer. That revelation helped secure criminal convictions against several tobacco companies for misleading the public, as well as billions of dollars in settlement payments for victims.

Merchants of Doubt also features Steve Milloy, a paid advocate for the tobacco giant Phillip Morris and coal company Murray Energy. “Dioxin, pesticides, chemicals in general—there’s no evidence that these are harming us,” he says in one scene. When Pruitt announced the EPA’s new science policy on Tuesday, Milloy was one of the few people invited to the event—reporters were not—because he has been a longtime proponent of the “secret science” rule. He was also quoted in nearly every major news outlet’s story about it, sometimes referring to himself in the third person.

“I look at it as one of my proudest achievements,” he told the trade publication E&E News. “The reason this is anywhere is because of Steve Milloy.”

Pretty cool when your career's work [EPA science transparency] is front-page news in all these papers and you're quoted in each report. pic.twitter.com/V1avq1EU2d

— Steve Milloy (@JunkScience) April 25, 2018

Milloy has long rejected established science, arguing against the overwhelming body of peer-reviewed literature linking secondhand smoke to cancer, human activity to global warming, and air pollution to premature death. He calls these bodies of research “junk science,” primarily because they are based on human health data, which is confidential due to privacy laws. Though hundreds of scientists have approved these studies through extensive peer review, Milloy has said the results aren’t trustworthy, and has sought to disqualify them from being used to make regulations.

Glantz says this is a tactic originated by the tobacco industry, which in the 1990s was getting increasingly frustrated by the number of studies linking their product to health problems. “They realized that, rather than fighting every single study that came out linking them to cancer, if they could get the rules of evidence changed, they wouldn’t have to worry about it,” Glantz said. So, tobacco companies came up with a reasonable-sounding set of rules for “transparency” in research, and created an organization called The Advancement of Sound Science Coalition to advocate for them.

The group disguised itself as an independent nonprofit, “advocating the use of sound science in public policy decision making,” according to its now-defunct website. It was based out of Milloy’s home. “They tried to place standards for interpreting epidemiology that made it impossible to implicate secondhand smoke as causing anything bad,” Glantz said. They did not succeed, and public opinion overwhelmingly shifted toward the belief that secondhand smoke indeed was harmful.

Public opinion has not reached that level of consensus for global warming or air pollution. Thus, Pruitt’s industry-friendly EPA has been able to implement similar standards without much fanfare. According to The Washington Post, “The proposed rule would only allow the EPA to consider studies where the underlying data is made available publicly. Such restrictions could affect how the agency protects Americans from toxic chemicals, air pollution and other health risks.” Glantz thinks the restrictions will harm not only public health, but public knowledge. “This is a huge threat to the whole scientific decision-making process,” he said.

If science based on confidential human health information couldn’t be used by the government, the tobacco industry likely never would have been subject to strict regulation, nor would companies like Philip Morris have had to pay billions to the people their products harmed. The fossil fuel industry may well avoid that fate, thanks to Pruitt and Milloy. “Corporate interests benefit from you being ignorant,” Glantz said. “If you don’t know the magnitude of the problem, then they don’t have to worry about you demanding they do something about it.”