“You have seen how a man was made a slave,” Frederick Douglass wrote in his 1845 autobiography, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. “You shall see how a slave was made a man.” These words herald the moment when Douglass masters his master, the sadistic overseer and “negro-breaker,” Edward Covey, seizing him by the throat. More remarkable than Douglass’s physical prowess was the fact that he lived to write about this at all: In addition to the beatings and other miseries, Douglass endured severe cold that left gashes in his feet pronounced enough to cradle his pen. “Written by himself” is Douglass’s subtitle, a phrase that resounds throughout early African American autobiographical writing. Douglass’s books, along with photographs of the author, portrayed a man who was fully self-composed. The story was the self.

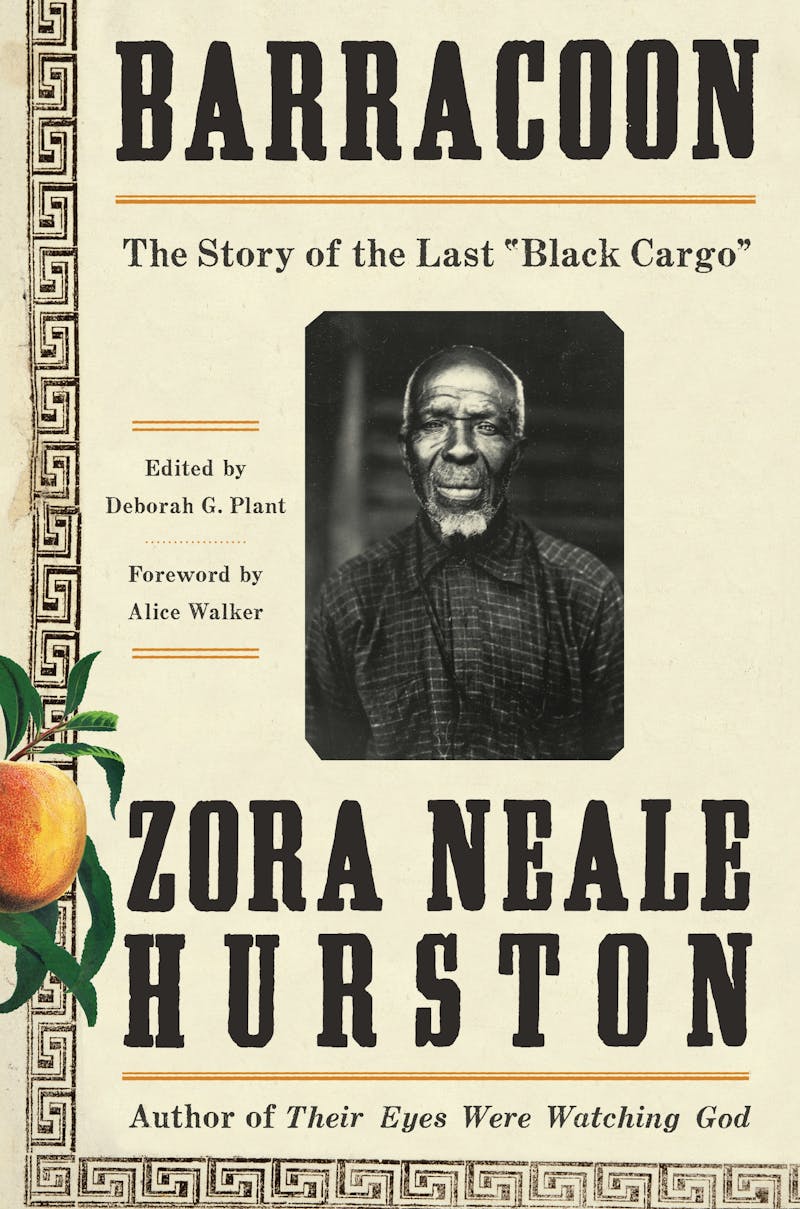

“This is the life story of Cudjo Lewis, as told by himself.” Zora Neale Hurston similarly begins her preface to Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” Barracoon is not a slave narrative in the traditional sense, and its subject, Cudjo Lewis, never mastered the written word. But the story he had to tell filled an important gap in the grand narrative of the African American experience. Born Oluale Kossola in the 1840s, Lewis was believed to be the last survivor of the transatlantic slave trade. He was, Hurston writes, “the only man on earth who has in his heart the memory of his African home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery; and who has sixty-seven years of freedom in a foreign land behind him.” Like Douglass, Lewis was himself a story; his survival was proof of a people’s vitality.

Trained as an anthropologist, Hurston was interested in the universal, the profound, and the ordinary. “How does one sleep with such memories beneath the pillow?” she wonders at the commencement of her conversations with Lewis. “How does a pagan live with a Christian God? How has the Nigerian ‘heathen’ borne up under the process of civilization? I was sent to ask.” Her drive to understand brought her to Cudjo Lewis’s gate in December 1927, and it would direct her for her entire life, as she investigated and preserved, in her works of ethnography and fiction, the complex world of black folk traditions. Barracoon is not just the story of a man, Cudjo Lewis. It is also the story of a woman on her way to becoming a preeminent collector of black folklore.

Hurston’s drive to know—to tell and embody stories that other people, powerful people, considered unbecoming—would also lead to personal anguish and earned her as many enemies as admirers. For a long time, her detractors were victorious. Some of this criticism responded to her political views: She took a public stance against the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision and expressed skepticism of integration as an imperative, in general. Her works also met with harsh judgment and ultimately fell out of print: Barracoon is published for the first time only this year. The life of Zora Neale Hurston was never destined to be easy.

Author, ethnographer, folklorist. Genius of the South. Wandering minstrel. Barnard’s “sacred black cow.” Born in Notasulga, Alabama, in 1891, Zora Neale Hurston was all of these things and many others. In 1918, she enrolled at Howard University, where she began to use fiction as a means of exploring the culture that had produced her, namely the black rural community of Eatonville, Florida, a town whose laws had been codified by her father, a longtime mayor. She received a scholarship to Barnard College, where she was the only black student, and found a mentor in the esteemed anthropologist Franz Boas.

Hurston was 36 years old and working as a researcher for the eminent black historian Carter G. Woodson when she first met Cudjo Lewis in the summer of 1927. She conducted her initial interviews with Lewis as Woodson’s employee and with encouragement from Boas. That first attempt to collect Lewis’s story was not terribly fruitful. She published an article about him in Woodson’s Journal of Negro History, supplementing her own material with passages from Historic Sketches of the Old South, a study composed by Emma Langdon Roche in 1914. It was plagiarism, pure and simple, and the only such instance in a career otherwise distinguished by ingenuity and originality.

Hurston returned to Lewis in December with a new sense of purpose and urgency. As she explained to Langston Hughes, 86-year-old Lewis was “old and may die before I get to him otherwise.” (He actually lived to the age of 95.) But anthropological work is painstaking and time-consuming, and so to pursue her project, she needed financial support, which would bring its own difficulties and demands. By the time of her second visit to Lewis, Hurston had entered into a complicated relationship with the white woman who would serve as her patron in some form for the next five years, Charlotte Mason. The widow of a well-established New York physician, Mason had at her disposal generations of inherited wealth and circulated among the social and political elite. She had a passion for the “primitive,” however, and had committed herself to the preservation of a disappearing black culture.

Mason’s partner in this quest was the writer and impresario Alain Locke, who had been Hurston’s mentor at Howard. There, Locke had created a literary magazine, the Stylus, which published two of Hurston’s short stories. He had arranged the meeting between Hurston and Mason and had also introduced Mason to Langston Hughes. Like Hurston, Hughes joined a circle of protégés that included sculptor Richmond Barthé and caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias. They were all instructed to address Mason as “Godmother.” “I went to see Mrs. Mason today and I think that we got on famously. God, I hope so!” Hurston wrote to Hughes in September 1927.

Hurston was relieved and excited to have the financial support, but she was also intrigued by Mason herself. A surviving photograph shows a softly outlined Mason in pearls and granny glasses. Apparently, this harmless-looking spinster had a tongue like a “knout, cutting off your outer pretenses, and bleeding your vanity like a rusty nail. She was merciless to a lie, spoken, acted or insinuated.” Mason could read her mind, Hurston claimed, and dressed her down when she didn’t like what her protégé was thinking. “You are dissipating your powers in things that have no real meaning,” Mason would chastise her. Mason believed in the supremacy of black vitality. Ironically, she saw herself as protecting that vitality from white corruption.

The employment contract Mason drew up for Hurston was rigid, comprehensive, and “choked with legalese,” Hurston’s biographer Valerie Boyd has written. It provided Hurston with $200 a month, a car, and a camera to “collect all information possible, both written and oral, concerning the music, poetry, folklore, literature, hoodoo, conjure, manifestations of art and kindred subjects relating to and existing among the North American negroes.” Their agreement explicitly stated that Hurston would be acting only as Mason’s agent, her eyes and ears in the field. She recognized Hurston’s genius, but she wanted to control it, and forbade Hurston from using what she collected for her own material purposes. She did not want Hurston to seek fame or glory for her work, but Mason herself wanted to remain in the shadows.

Mason also helped Lewis financially and asked Hurston to follow up on occasions when Lewis did not receive her money. He called Mason a “dear friend.” But Mason didn’t like it at all when Lewis tried to earn money from his story on his own. She conveyed her displeasure when he sold part of his narrative to a reporter. Lewis dictated a letter of apology. Through Locke, Mason explained that she wanted to shield Lewis from exploitative whites, whom she resented for plundering “material that by rights belongs to another race.” She also made it clear to Lewis that his story did not actually belong to him.

In Barracoon, Hurston sets the stage for Lewis’s unique story by telling readers what not to expect. The book, she writes, “makes no attempt to be a scientific document.” Instead, her job, as she saw it, was to “set down essential truth rather than fact of detail, which is so often misleading.” The history of the transatlantic slave trade, Hurston contended, had for too long been dominated by information about ships, wars, kings, and mutinies; accounts of sales, profits, and losses. “All these words from the seller,” Hurston wrote, “but not one word from the sold.” Her point was well-made. Even as a corpus of slave narratives circulated, much of the story of what happened to black bodies on these shores was yet to be told.

Lewis hadn’t been cargo as much as contraband. The slave trade had been outlawed for more than 50 years by the time he was captured and sent across the Atlantic in 1860 to Alabama. Unofficially, the trade in black bodies had continued: In her thorough introduction, Deborah Plant, a Hurston scholar and the editor of Barracoon, explains that among the African groups and leaders who colluded in the continuation of the illegal practice was King Ghezo of Dahomey, in West Africa. The king “instigated wars and led raids,” taking prisoners “with the sole purpose of filling the royal stockade” and enriching himself.

When Lewis was around 19 years old, he survived one such raid, when “a whooping horde of the famed Dahomian women warriors” descended on his town. The warriors butchered the people and used the heads of Lewis’s kinsmen as decoration for their belts. Lewis tried to escape, but the invaders overpowered him. “They take me and tie me,” he told Hurston. “I don’t know where my people at. I never see them no more.” Lewis was captured and held for weeks in the barracoons of Ouidah, near the Bight of Benin. Eventually sold to James Meaher, he was among the captives brought to America on the Clotilda, the last-known ship to bring enslaved Africans to America. Upon arrival in Alabama, Lewis endured over five years of slavery before Union soldiers delivered the news of his freedom. He spent the rest of his life in a settlement of formerly enslaved Africans called Africatown.

Hurston had never heard a story like Lewis’s. Although Lewis was hardly inexperienced in the art of storytelling—other folklorists, as well as journalists and historians, had come to visit him; a folktale he shared appeared in The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Locke—Hurston worried about the effect of her presence on Lewis and even expressed regret that she had “come to worry this captive in a strange land.” The act of remembering took an emotional toll on him. Many of his stories—about the tragic deaths of his children, his loneliness for his deceased wife, as well as his memories of the slaughter he barely survived—caused the old man to weep.

Hurston was moved and brought him gifts, food and insect powder, to smooth the way for his telling. Lewis and Hurston spent a lot of time eating. They shared peaches, watermelon, once “a huge mess of steamed crabs”; the invisible but integral role that food plays in Hurston’s reception of Lewis’s story calls to mind the “hungry listening” that facilitated the tale at the heart of her most famous novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. They became friends, but Lewis annoyed Hurston, too. His enthusiasm for Christianity bothered her; she was sure he was hiding something (“He pretended to have forgotten all of his African religion,” she wrote in her 1942 book Dust Tracks). As someone who would soon undergo a hoodoo initiation ritual—in which she was required to lie naked on top of a snake skin for 69 hours, without food or water—Hurston was miles apart from Lewis, the experiential distance between them as wide as the Atlantic.

Even more terrible to bear than Lewis’s memories was, for Hurston, the death of a foundational myth. She had grown up believing that slavery was a consequence entirely of white might over black. The dominant narrative of American slavery described, as Douglass had, a world of white villains and black victims. “But if the African princes had been as pure and as innocent as I would like to think,” she now wrote, “it could not have happened.” Cudjo Lewis was a man made a slave not by the crack of an overseer’s lash but through betrayal by other black people in his own home country. It was chilling, the revelation, but it also suited her world view. “It impressed upon me the universal nature of greed and glory,” she wrote.

All of her life, Zora Neale Hurston was driven by a passionate, bottomless interest in the human condition. Against the literary fashion of her time, she did not want to write a social document but to explore universals: “From what I had read and heard, Negroes were supposed to write about the Race Problem. I was and am thoroughly sick of the subject. My interest lies in what makes a man or a woman do such-and-so, regardless of his color.” In a 1928 essay called “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” she decried “the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal.” In the 1930s, when Hurston was in her creative prime, protest literature, with its grim depictions of black life, dominated the popular landscape. Richard Wright enjoyed critical and commercial success in 1938 with his first book, Uncle Tom’s Children, whose stories revolve mainly around racist violence. Though she found “some beautiful writing” in the book, it was, to her, “a book about hatreds.”

When she reviewed Wright’s book, Hurston had recently published Their Eyes Were Watching God. The first paragraphs of her novel reveal the grand ambitions of the narrative: “So the beginning of this was a woman and she had come back from burying the dead.” Replete with Biblical allusions, Their Eyes follows its protagonist, Janie Crawford, on a search for romantic love and spiritual fulfillment. It is a story about marriage and intimacy, as well as a black folk iteration of the classic tale of a singular hero on a quest. For the sights and sounds of this story as well as her other work, Hurston made a creative return to her hometown of Eatonville, where she grew up appreciating the intimate link between music, meaning, and the natural world in African American oral culture. The entire novel is made up of conversations that honor the everyday patterns of Southern black speech. Overall, however, the novel is about the common predicament of being human. In Hurston’s particular lies the universal.

The serious intentions of the novel were lost on critics. “Miss Hurston can write,” Wright conceded stiffly in a review of Their Eyes Were Watching God, “but her prose is cloaked in that facile sensuality that has dogged Negro expression since the days of Phillis Wheatley.” Richard Wright was not alone among critics who saw Hurston’s celebration of the black folk as a capitulation to racist stereotypes of black people. The vernacular idiom that Hurston valued Wright and others deprecated as backward; her literary concern with romantic love was considered frivolous and even vulgar. What Wright composed was less a review than a condemnation. “Miss Hurston voluntarily continues in her novel the tradition which was forced upon the Negro in the theatre, that is, the minstrel technique that makes the ‘white folks’ laugh.”

Hurston was furious when she read Alain Locke’s evaluation of her book. His accurate description of Their Eyes as “folklore fiction at its best” was faint praise in a review that ultimately dismissed Hurston for her failure to produce “social document fiction.” According to Ralph Ellison, the novel “retains the “blight of calculated burlesque that has marred” Hurston’s work. Similar condemnations would attend assessments of her work and person for generations to come. In his landmark 1971 study, In a Minor Chord: Three Afro-American Writers and Their Search for Identity, Darwin Turner’s analysis of Hurston’s work attacks Hurston as an individual and indicts her as “a wandering minstrel.”

Not until after her death did her work begin to receive a critical mass of serious attention in literary circles. Hurston was indigent when she died, a resident of a welfare home. Beloved in her community, she was unknown as a writer, or, as Alice Walker later christened her, “a Genius of the South.” With no one to claim them, her papers were burned. Fortunately, a friend of Hurston’s, a local deputy, happened to be walking by while the fire burned and rescued many of her effects. Today, manuscripts, letters, and photographs with charred edges are housed at the University of Florida.

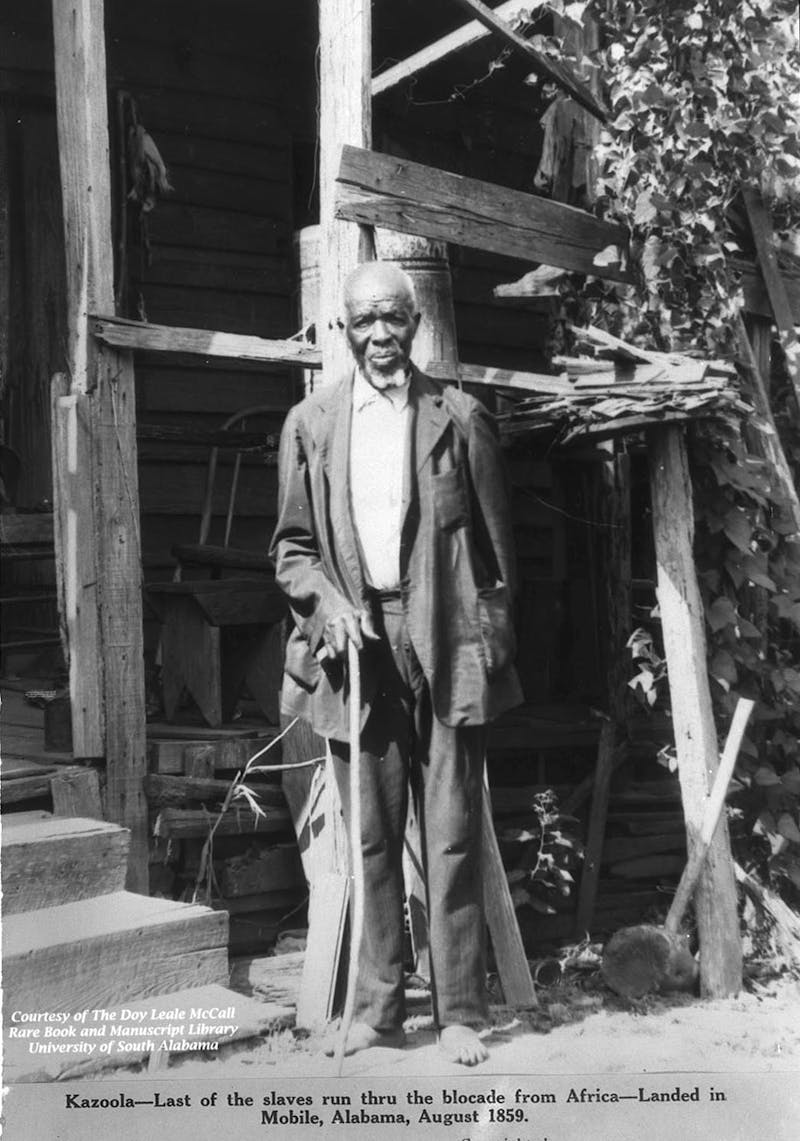

Did Hurston find the answers she came in search of when she arrived at Cudjo Lewis’s door? Certainly, she received an education in the history of American slavery. She gave him something, too: a photograph. “I’m glad you takee my picture,” Lewis told her when she asked permission to photograph him. “I want to see how I look. Once long time ago somebody come take my picture but they never give me one. You give me one.” Lewis changed into a suit for the photograph but removed his shoes. “I want to look lak I in Affica,” he explained. He wanted to be photographed standing among his family, in the local cemetery. In its final chapter, the story of Cudjo Lewis was less about a man than a community.

Hurston’s own grave in Fort Pierce had no marker until Alice Walker made an historic journey to Florida in 1973 to rectify this wrong. Walker played a crucial role in a collective effort on the part of black women writers and scholars to resurrect and commemorate Hurston, setting off a domino effect now two generations strong. Walker narrates her journey of discovery—geographic and metaphorical—of our first, best, and most in two elegant essays, “Looking for Zora” and “Zora Neale Hurston: A Cautionary Tale and a Partisan View.” “We are a people,” Walker writes in the latter essay. “A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children and, if necessary, bone by bone.”

There is a lot to learn from the life of Zora Neale Hurston, just as much as there is to learn from the life of Cudjo Lewis, from the stories they each embodied and left behind. “After seventy-five years, he still had that tragic sense of loss,” Hurston wrote of Lewis in Dust Tracks. “That sense of mutilation. It gave me something to feel about.” It is tempting to see Hurston’s half-burned effects as another kind of cultural violence, a physical manifestation of what the literary critic Mary Helen Washington describes as the “intellectual lynching” Hurston endured. Perhaps. But we might also imagine them as a congregation of paper phoenixes, rising.