William Roughead wasn’t the kind of writer who liked to indulge in outrage. The Glasgow lawyer, who began attending murder trials in 1889 at the age of 19—for curiosity’s sake until it became his professional avocation—much preferred to write about crime in a dry, droll manner. The cases he covered, with notable defendants such as Madeleine Smith, Constance Kent, and Katherine Nairn, were colorful enough to speak for themselves, the evidence substantive enough for readers to reach their own conclusions. Over six decades writing about the most notable criminal proceedings in Britain (the best of these essays are collected in Classic Crimes), Roughead did not need to juice his style with the seeds of anger. That’s why so many, myself included, regard him as the dean of the modern true crime genre.

But the Oscar Slater case was different. Roughead not only attended the trial of Oscar Slater in Glasgow in May 1909, writing it up for the Notable Scottish Trials series, but he also believed that the guilty verdict, arrived at after barely an hour of deliberation, was wrong. There was, in Roughead’s estimation, no evidence that Slater, a German Jewish immigrant, was even in Glasgow when Marion Gilchrist, a wealthy woman in her 80s, was robbed and bludgeoned to death in her apartment. And the main witnesses, notably Gilchrist’s maid Helen Lambie and a neighbor, Mary Barrowman, kept changing their stories. Even when Slater’s original death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, Roughead’s outrage did not subside.

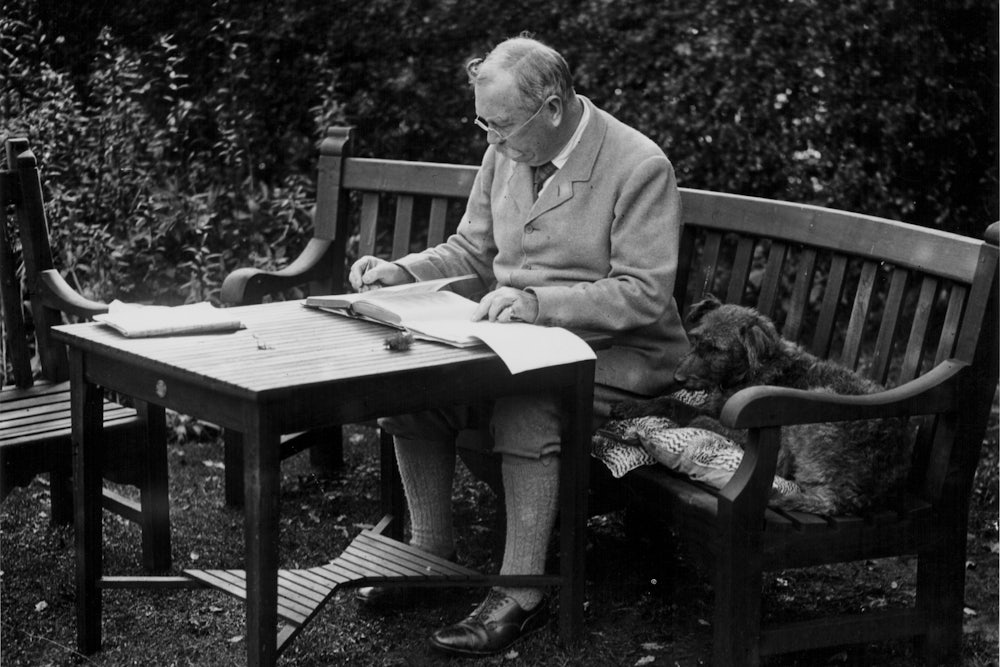

Roughead broadcast his disbelief in Slater’s guilt from the first, to anyone who would listen, enjoining the most famous detective fiction writer in the world, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in his cause. The case transformed Roughead from observer to participant. He even testified at a hearing, nearly 20 years after the original trial, to determine Slater’s ultimate fate: Would the man stay in Peterhead Prison for a crime he did not commit, or would he finally be freed? Years after that verdict came in, Roughead wrote a fresh essay—his fourth—on the affair in 1935. He was not shy about casting blame for the cascade of injustices that bedeviled Slater, nor did he hesitate to give credit where it was due. For Conan Doyle’s advocacy of Slater, Roughead called him a “paladin of lost causes and champion of forlorn hopes.”

Slater’s plight foreshadows so many future wrongful conviction stories, in which belief that the system will ultimately work is shattered by its cruel unfairness, its sacrifice of innocent defendants at the altar of wins and losses. The case never quite fell out of cultural consciousness—certainly not in Britain, and Scotland in particular, where the sustained outcry led to criminal justice reforms, including the institution of a proper appeals court. This year, his story has been having something of a revival, with a BBC radio documentary by crime writer Denise Mina and Margalit Fox’s splendid new book Conan Doyle For the Defense. How, both ask, despite the flimsiest of circumstantial evidence, was Slater so obviously and badly railroaded? And how did the very people who set out to defend Slater end up turning against him?

Conan Doyle For the Defense cannot resist structuring itself as a detective novel, though the whodunit is less about who killed Marion Gilchrist and more about who framed Oscar Slater. The ingredients are too good to pass up: a famous detective novelist actually playing detective, a man serving time for a murder he did not commit, and a criminal justice system slowly, and reluctantly, reckoning with the advent of forensic science—fingerprints were around when Slater was arrested and convicted, but in one of so many missed opportunities to right the wrong, never used.

As both Mina and Fox observe, Slater’s case played out like the Dreyfus Affair, which a decade earlier had seen a French army officer wrongfully convicted of treason. Slater, like Alfred Dreyfus, was Jewish, and thus “other” in protestant-dominated British culture. Slater did not speak English well, his heavy German accent frequently garbling words and making him misunderstood. He was married, but consorted with sex workers, had a criminal record, and made his money as a professional gambler. Slater also owned a small hammer, a weapon sometimes necessary in his line of work. He traveled under assumed names. One of these names—Anderson—got him in trouble: It was the name on the pawn shop ticket for a brooch that turned out to have been stolen from Marion Gilchrist’s apartments. This was the first seed in the false narrative that undid him.

The second seed was the then-current vogue in criminal investigation: pseudoscientific identification methods devised by Cesare Lambroso and Alphonse Bertillon. Police detectives eagerly adopted these methods, which linked criminality to specific physical traits like the shape of a person’s head or the size of his nose. That these methods were backed by little scientific evidence hardly mattered. They also often led to the arrests of people from certain ethnic groups, or those who fit certain stereotypes. Because Slater was deemed “undesirable”, with his foreign accent, his Jewish background, his dissolute lifestyle, and since murder was the domain of “undesirables”, police deduced that Slater must have done it—“preposterous reasoning,” Fox observes, that led to “to the detriment of justice.” Meanwhile, fingerprinting—a solid, scientifically backed technique—was never employed in the Slater case, a true “what might have been” if there ever was one.

If Slater was akin to Dreyfus, then Arthur Conan Doyle ended up as Emile Zola, who helped bring about Dreyfus’s release with his 1898 open letter, J’Accuse! There was much in the prosecution’s case for the detective novelist to find fault with, as he first outlined in The Case for Oscar Slater (1912). Slater’s hammer, he pointed out, was too small to be a murder weapon. He used assumed names to hide from his wife, not from police. He was nowhere near the crime scene, no matter how hard police tried to place Slater there. And the jury verdict—nine finding guilty, five “Not Proven”, and two innocent—wouldn’t have been enough to convict him in England, where jury verdicts have to be unanimous.

At first, Conan Doyle’s crusading efforts went nowhere. After a 1914 inquiry upheld Slater’s conviction, despite concerns lodged by a police detective, Conan Doyle raged: “How the verdict could be that there was no fresh cause for reversing the conviction is incomprehensible. The whole case will, in my opinion, remain immortal in the classics of crime as the supreme example of official incompetence and obstinacy.” He would work on the case off-and-on, in between writing novels and going deep into a Spiritualism phase, until 1925, when Slater smuggled a handwritten plea for help to Conan Doyle via a newly-released prisoner.

There wasn’t any fresh evidence or new revelation. He just wanted someone—especially someone with as much renown as Arthur Conan Doyle, who had advocated for him a decade before, but seemed to have moved on—to stand up for him. The next two years would prove pivotal. A book by the journalist William Park, The Truth About Oscar Slater (written with Conan Doyle’s emotional and financial support and published in March 1927) uncovered further instances of fabrication by law enforcement: the original search warrant on Slater, Park revealed, had actually been obtained under false pretenses. Park’s book finally seemed to wake Scotland up to Slater’s plight, and when he faced another hearing—with Conan Doyle, Roughead, and Park all in attendance or giving testimony—it led, at last, to his release.

Conan Doyle For the Defense is most successful when it loosens

itself from conventional mystery plotting and focuses more on the principals

and their emotional states. Slater, in his letters from prison to family

members he will hardly see for the next two decades, emerges in all his

complexity, his personality ranging from even-tempered to outright despair.

“You write me in your letters that there is no wonder if I have lost interest

in you,” he wrote to his sister, Malchen, late in his imprisonment. “I can only

lose interest in you when I cease to exist.” And to a family friend in 1910: “I

am a broken and a ruined man and will—so long as I live—make every endeavor—so

far as possible—to free my family from this awful shame.”

Conan Doyle, by contrast, is fueled by principle, his outrage stoked when court decisions do not go Slater’s way or when the public seems largely uninterested in the case, and then elated when, at last, the Scottish government finally nullifies Slater’s conviction. “Who can restore the vanished years?” Conan Doyle wrote in a thunderous essay introducing Park’s book. “It is indeed a lamentable story of official blundering from start to finish.”

For a man wrongfully convicted and for a detective novelist,

Slater’s release should have been a perfect ending. It was no such thing. Once

Slater was freed from Glasgow prison in 1928, he faced narrowed prospects. The

“Slater” name, and its associated infamy, slammed doors on professional

opportunities and brought back painful memories, so he reverted back to his

birth name of Leschziner. Not only was the real murderer never properly

identified, but the relationship between Slater and Conan Doyle devolved into

something ugly: By the time Conan Doyle died, in 1930, Slater and he were

estranged. Worse, the estrangement had its roots in a dispute over money. The

Scottish government gave Slater six thousand pounds in compensation when he was

released; Slater took the money, since he had none at the time, but didn’t

realize that Conan Doyle expected to be paid for his considerable time and

expense in aiding Slater’s defense.

Slater’s understandable need for a short-term need for money clashed with Conan Doyle’s “deep, abiding principle” that “absolute probity in fiscal matters...was one of the canonical imperatives of the upright life.” There was no ironclad agreement between the two men that Conan Doyle would be paid, only an assumption on his part. Their relationship unraveled, with Conan Doyle going so far as to attack Slater by letter: “You seem to have taken leave of your senses. If you are indeed responsible for your actions, then you are the most ungrateful as well as the most foolish person whom I have ever known.” The two men went to court over who was entitled to the six thousand pounds, ultimately settling for a mere 250 pounds only months before the detective writer died in July 1930.

As Fox notes, reading their “increasingly vitriolic” letters, Conan Doyle treated Slater “more as an archetype than an individual.” Slater, the cause, the avatar for justice denied, was worth every fight, whereas Slater, the “disreputable, rolling-stone of a man,” proved a deep disappointment. To some credit, Conan Doyle understood that “eighteen years of unjust imprisonment” had left its mark on Slater. But what he did not fully grok was that Slater deserved to be treated as a real and complex person, not a one-dimensional character. Conan Doyle had dwelt so long in the land of Sherlock Holmes stories, where ingenious reasoning led to audacious solutions, that he could not see how Slater defied traditional narrative—and that he was far messier than any fictional character of Conan Doyle’s devising.