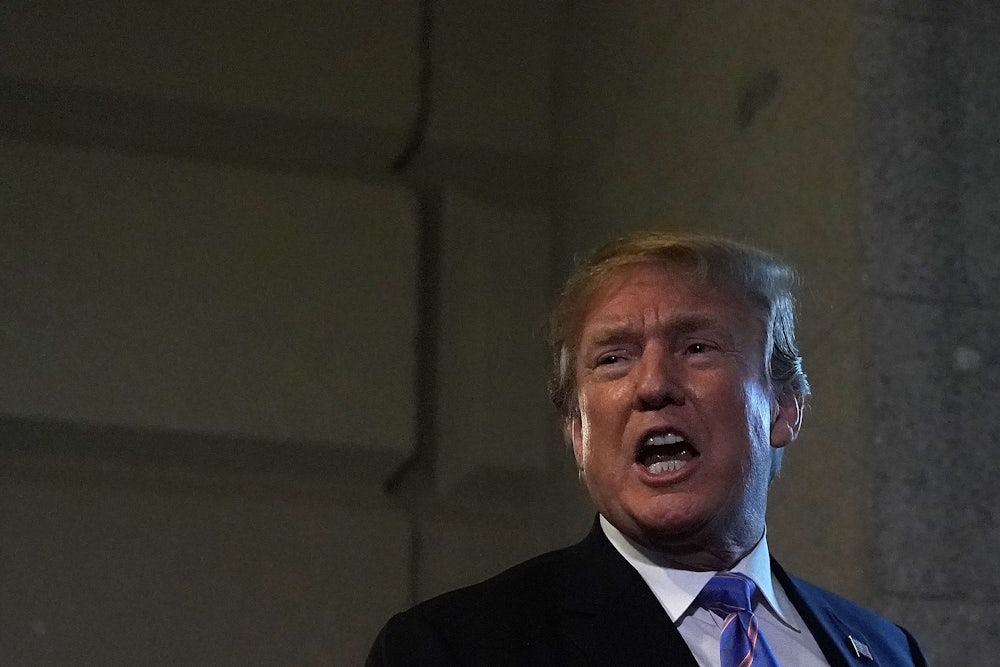

“Democrats are the problem,” Donald Trump tweeted on Tuesday. “They don’t care about crime and want illegal immigrants, no matter how bad they may be, to pour into and infest our Country, like MS-13. They can’t win on their terrible policies, so they view them as potential voters!” Like many of Trump’s tweets, this statement contains both a lie and a slur. The Democratic Party bears some responsibility for the Obama administration’s immigration policies—humane and restrictionist alike—but it did not create the zero-tolerance policy that now breaks up families at the border. That policy belongs to Trump; he will be remembered for it, and for the rhetoric he has used to justify it.

“Infest” is not a word customarily used in reference to humans. We fear infestations of cockroaches or bedbugs or lice. To accuse people of infesting America is to dehumanize them.

This is not the first time Trump has referred to migrants in this way. Sanctuary cities, Trump once complained, are “crime-infested,” as if the presence of immigrants guarantees an outbreak of violence. He is also worried about their “breeding,” a word usually reserved for animal or insect mating: “Soooo many Sanctuary areas want OUT of this ridiculous, crime infested & breeding concept,” he tweeted in April.

Trump did not invent this language from whole cloth. Modern history is full of examples of political regimes that has described certain populations as subhuman—often to justify treating them as such. In the most extreme cases, that rhetoric preceded mass killing.

“One of the common threads of any genocide is its justification. In order to be able to execute it on a mass scale, a lot of people have to buy into it and agree that it’s the appropriate thing to do. And so any genocide begins with the dehumanization process,” explained William Donohue, a professor of communication at Michigan State University who has studied the function of dehumanizing language in the Rwandan genocide.

In one influential speech, a Hutu politician compared Rwanda’s Tutsi population to a particularly nasty insect. As Foreign Policy reported, Leon Mugesera in 1992 “told a crowd of supporters at a rally in the town of Kabaya that members of the country’s minority Tutsi population were ‘cockroaches’ who should go back to Ethiopia, the birthplace of the East African ethnic group.” Mugesera is hardly the only reason the Hutu people started slaughtering the Tutsi two years later; he was one powerful propagandist in a generation of propagandists. But radio broadcasts disseminated this language to radical Hutus and, in the opinions of human rights tribunals and experts like Donohue, spawned mass violence.

Nobody in the Trump administration has called for the killing of migrants. Violence is not government policy, but rather a side effect of policy; the U.S. government deports migrants back to their home countries, which many have fled out of fear of being killed by gangs or abusive husbands. There is no race war. Nevertheless, words like “animal” and “infest” perform pernicious political work in any context. “Any time you use any of those metaphors, it’s meant to try to reduce sympathy for a particular group, so people see that group as not deserving of compassion. It’s a kind of objectification,” Donohue said.

Considered alongside the spectacle of human beings in cages and camps and “tender age” shelters, Trump’s language has inspired comparisons to the Third Reich. “This is the United States of America; it’s not Nazi Germany,” Senator Dianne Feinstein of California told MSNBC’s Chris Hayes on Monday. It’s a controversial metaphor, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions vehemently rejected it on Monday evening: “In Nazi Germany, they were keeping the Jews from leaving the country,” he said.

It is fraught to make any comparison to the Nazis, as it threatens to dilute their unique horrors. But Andrea Pitzer, author of One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps, considers it accurate to refer to Trump’s government-run detention camps as concentration camps and sees other parallels between America today and Germany in the early 1930s. “What’s often forgotten is that nearly five years passed before the government arrested German Jews en masse and put them into the concentration camp system. Outside the camps, the Nazis were passing laws against German Jews the whole time, stripping them of citizenship and denying them access to public services and jobs,” she wrote in an email to The New Republic.

To build public support for their anti-Semitic policies, the Nazi government constructed an elaborate propaganda machine. White, German families were presented as whole and hearty—and under threat. “In their rhetoric, Nazis talked about Jews using animal terminology (of rats, insects, and pigs) and as unassimilable foreigners, and described them using language of disease and sexual deviance,” Pitzer continued. The Eternal Jew, an anti-Semitic propaganda film released in 1940, compares a map of Jewish migration to a pulsating pile of rats; Jews weren’t just considered animals, but plague-bearing animals at that.

Republicans have not compared immigrants to rats, though a New Jersey official once bizarrely compared them to raccoons. America is not Nazi Germany; it is not Rwanda in 1992, perched uneasily on the edge of an abyss. If parallels exist, it is because prejudice often uses a common language. “The rhetoric of hate is portable and flexible—it can be used anywhere against anybody,” Pitzer wrote.

The United States has its own history of dehumanizing populations in order to enslave and massacre them. Thomas Jefferson once compared enslaved Africans to wild animals, as Nicolaus Mills noted at The Daily Beast. “But as it is, we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other,” Jefferson wrote in 1820. The widespread belief that Africans were not fully human, but rather subhuman, propped up the Confederacy’s defense of itself. Abraham Lincoln, one Alabama commissioner wrote at the time, would consign the South’s “citizens to assassinations, her wives and daughters to pollution and violation, to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans.”

In a similar fashion, the idea that Native Americans are subhuman propelled not only a campaign of slaughter against them, but a program of forced migration and a system of boarding schools intended to force assimilation on their children. President Andrew Jackson, defending his government’s removal policy, bragged, “It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from

the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude

institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them

gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast

off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”

Trump started down Jackson’s path on the day he launched his campaign, when he referred to Mexican as “rapists” coming over the border, and he inched closer toward today’s border camps with every rant about “bad hombres” and MS-13 “animals.” As Jamelle Bouie argued for Slate on Tuesday, “The ‘animal’ comments help explain his core beliefs, which his recent remarks make crystal clear: President Trump sees all Hispanic immigrants—and not just MS-13—as ‘animals’ threatening the cultural and racial integrity of the United States.”

It isn’t wise to fearmonger, but it’s important to remember how violent rhetoric can lead to violent outcomes—and so can concentration camps. “I went into Rohingya camps in Myanmar in July 2015 and also interviewed locals in town who supported their segregation,” Pitzer wrote. “I was struck by two things: the first was how similar the extremists’ rhetoric was to 1930s Nazi propaganda, and also how similar it was to the things Donald Trump was saying in the first weeks of his campaign, which began not long before my trip.”