Diane Williams seeks to stun, in something near the literal sense of the word. Acts of accidental violence bookend her story “The Nature of the Miracle,” which is only four paragraphs long. A bottle of sparkling water shatters on a kitchen floor, and the woman who dropped it knows she should leave her marriage and “run to the man who has told me he does not want me.” Another woman leans over to start the dishwasher and spears her eye on “the tip of the bread knife, which is drip-drying in the dish rack.” It’s an “accident,” Williams writes, though it’s impossible to tell what really happened, and what “really happened” does not matter. Her aim is to show how even the most gentle scene contains potential for danger.

Williams is often called an “experimental” writer, a term she has dismissed as a way of branding authors in the literary marketplace. But it’s easy to see why her work invites the description. Her stories are much shorter than most. Some are no longer than two sentences, a length sometimes called “flash fiction” for its ephemeral quality. There are no first sentences full of orienting details, no dramatic dialogue, no neat epiphanies in a story’s final lines. A concluding sentence is more likely to open up a story than to resolve it. (“I am trying to be independent. Is that wrong?” ends one.) Characters remain anonymous, or else they are introduced suddenly, with proper names but seemingly without pasts. Tones clash; idioms and allusions brush up against each other. Even her shortest stories, written in the simplest language, have a kind of uneven texture that forces a reader to proceed slowly.

One of Williams’s great themes is the dark underbelly of domestic life. Infidelity powers much of her fiction; there are no happy marriages, only longed-for or realized affairs. Household accidents stand in for the deliberate violence that characters wish would occur. More than a few stories take place in kitchens, where women habitually wield knives. Others take place at children’s birthday parties, at cocktail parties, on family road trips. Characters harbor secrets and interpret banal statements as signs of doom. In “The Uncanny,” a husband and wife dance at a dinner club; when the husband complains about the length of a song, the wife interprets his words to mean “he has not loved me for a very long time.” Everything means nothing or too much.

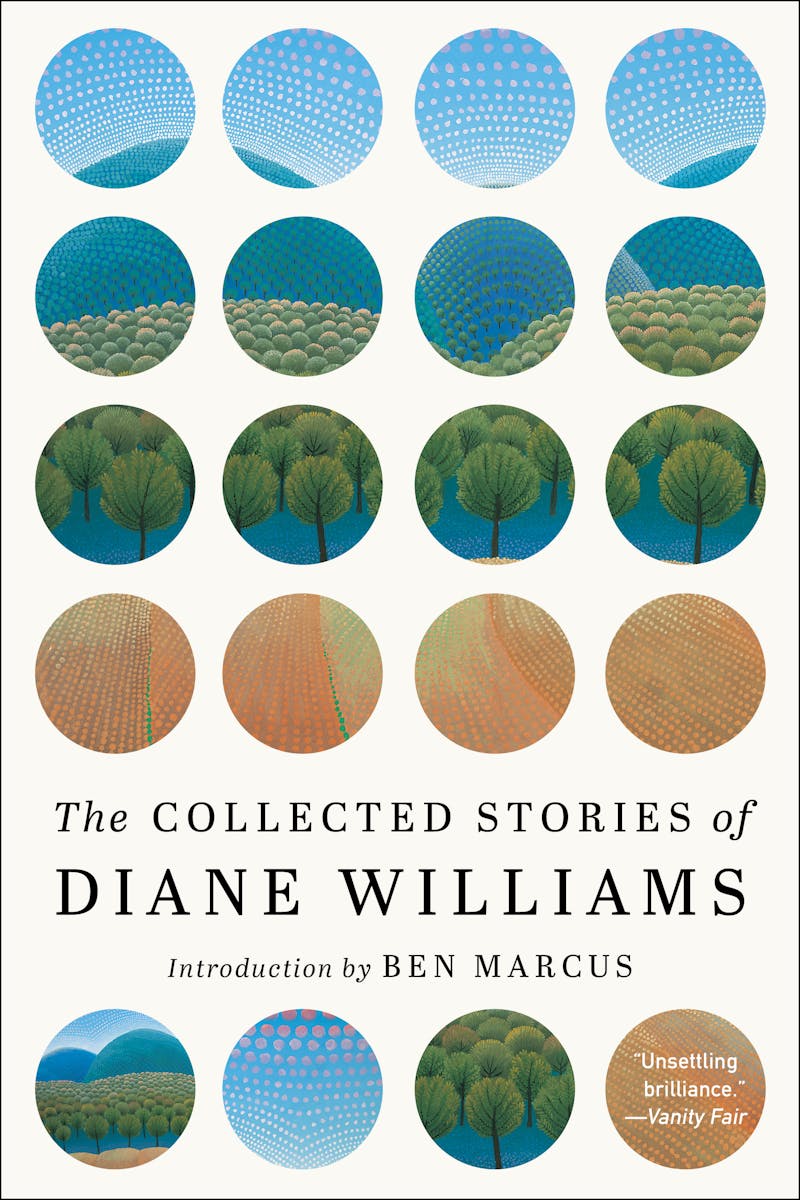

Despite their shared themes, this fiction has little in common with the suburban stories of John Cheever or Alice Munro’s small towns. In those authors’ works, realistic details are carefully selected; characters feel familiar; the world we read about conforms to the one we know. Spanning nearly 800 pages and three decades, The Collected Stories of Diane Williams presents domesticity as foreign and contrived, as an arbitrary and risky way to organize one’s life. In their weirdest moments, these stories can feel unreal, disconnected from the texture of experience; at their best, their abandonment of logic can feel like liberation, as they lay bare the disjointedness and confusion that structure so much of reality. The safest, most conventional life story (marriage, kids, a move to the suburbs) becomes something else: an odd assemblage of habits and objects and impulses, not even a story at all.

It’s tempting to describe Williams’s writing, with its run-on sentences and abrupt endings, as the antithesis to what we often call “workshop” fiction: stories focused on “craft,” full of elegant sentences, often associated with MFA programs, particularly the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. But Williams, too, was a workshop writer. In the mid-1980s, she studied with the renowned and controversial teacher and editor Gordon Lish, the man responsible for carving up Raymond Carver’s early short fiction (over Carver’s objections) and launching the writer’s career. Williams met Lish at a short-story seminar in Detroit, soon after she had started writing stories and had begun publishing them in literary journals and little magazines.

This wasn’t her first go at fiction: As a college student at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1960s, she studied with Philip Roth, whose influence can be detected in the sexual boldness of so many of her stories. She hadn’t planned to become a writer then; like many women of her generation, she was to marry and have children. After college, she worked briefly as an assistant at Doubleday in New York City (because she was a woman, she was forced into secretarial work) and, later, as a textbook editor. Soon enough, she married and moved to Chicago, then to the city’s suburbs. “We were going to be raising children,” she once explained to an interviewer—she had two sons—“and we thought that would be a kind of sweet, safe place to live with children.” If it was that, it was also stultifying and oppressive. Williams watched as her creative ambition went slack. She felt herself disappearing. Looking back on this time, she called it a kind of “soul death.”

When she began writing again, it was with a true sense of urgency. She published her first collection, This Is About the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time, and Fate, in 1990, when she was 44 years old. In these stories, Williams takes the familiar scripts of realist fiction (adulterous love triangles, disobedient children, dying parents), cuts them up, and then rearranges a few choice scraps until a scenario emerges, a sketch that is at once more ambiguous and more forthright than a more detailed story would be. We might not know how a woman came to be married, or why she might now want to leave, but we come to know her current desires intimately. These are portraits of people who are outwardly stable, but inwardly in flux.

Many of the stories are set in the suburbs, where couples argue and attend garden parties, where wives covet their neighbors’ husbands and husbands seize their neighbors’ wives. A story titled “Orgasms” finds a woman competing with her husband’s mistress; she hoards dark, envious thoughts the way the other woman must, she imagines, hoard orgasms. “All American” begins with a double confession: “The woman, who is me—why pretend otherwise?—wants to love a man she cannot have.” The narrator’s meditation on adulterous love bleeds into a shameful memory from childhood, with a few reflections on the use of force—and of the word “force”—thrown in along the way. None of these stories spans more than two pages, but in that time Williams establishes a character, a consciousness, and a social world brimming with desires that cannot be spoken aloud.

Williams went to Lish’s seminar, she said, because she understood that he was offering “the special chance to become hugely conscious of how language can be manipulated to produce maximum effects.” When we consider Williams alongside the other writers whom Lish educated and edited, her work can look quite similar to Carver’s or to fiction produced by other writers associated with the movement that came to be called “literary minimalism”: fiction that relied on simplicity, brevity, and excision to produce its uncanny, haunting effects.

Where Williams differs from a writer like Carver is in the sheer weirdness of so many of her sentences. Although she uses simple words—her prose has a kind of Dick-and-Jane quality—she arranges them in unusual ways. A reader can linger on each sentence, willing herself to comprehend it. Williams plays frequently with syntax, creating long, winding, sometimes difficult passages that bring to mind James Joyce and late Henry James. Some of her writing resembles stream-of-consciousness, as a character moves from one association to the next. “The orgasms—where do they go?—crawling up into—as if they could have—up into—dying to get in, ribbed and rosy, I saw seashells were the color moths should be, or the nipples of breasts, or the color for a seam up inside between legs, or, for I don’t care where,” muses one narrator, approaching then turning away from the painful scenarios her imagination conjures.

Other sentences reflect the rhythms of speech. “My Highest Mental Achievement,” a dramatic monologue and one of the strongest stories from her second collection, presents a self-interested lover taking her leave. “If I could know what happened the last time you had sexual intercourse with me, and what your opinion of it was, what your experience was with it, I would be so interested to hear,” the narrator says, request after request tumbling forth in a way typical of an anxious but voluble speaker. “It is so much better for me to be the one who loves rather than to be the one who gets loved!” she crows later. A common sentiment, perhaps, but one rarely expressed so baldly. There’s something refreshing about a speaker willing to pour forth her least flattering qualities.

Williams disobeys many of the laws of grammar, ending sentences with prepositions, starting with conjunctions, and generally appreciating the fragment as a unit of thought. She favors the dash as a way of breaking up or linking together sentences, as in this excerpt from “Ultimate Object”:

His peaceable plan—to lift and to unfurl, flat, round, yellow, black-speckled cakes—was the only other romantic transformation —not the product of imagination—going on in the place at the same time. And the man had no more right to be in this place—he was on the same shaky ground as she was, and as her friend was, by being there—which she saw him confirm with a smile.

The effect is a portrait of simultaneous action: The man is baking, the woman is watching him, a friend is hovering in the background. Yet each character remains separate, isolated in his or her own consciousness. Only the man, for instance, knows that the knife he used to kill a woman is lying in a cupboard nearby, and that the “woman’s naked, somewhat hacked body, decapitated and frozen, was in the institutional-freezer, adjacent to the stove.” With each additional clause, we move away from the world we recognize and into a scene straight out of Bluebeard’s Castle. The kitchen, we learn, is a place to cook and to create—and to store the most awful secrets.

There’s an intensity to Williams’s early stories that is missing from some of her later work. Reading the first two collections produces a rush, as if one has just narrowly avoided some disaster. Some of the most effective of these stories confront the frustrations and fears of motherhood. “Baby” is a wry, funny story about a sexually frustrated mother who is attending a baby’s birthday party, a particularly showy one at that, with “James Beard’s mother’s cake with turquoise icing.” She imagines how she would respond to potential sexual overtures (politely, she says) and gets annoyed at her husband, who refuses to mingle. The husband ends up leaving early, without the narrator: “he said to get a little—I don’t know how he was spelling it—I’ll spell it peace.”

“Pornography,” a story written in the headlong style that Williams deployed more frequently early in her career, finds a mother shouting after her son, who is biking toward an intersection known for its accidents. The mother herself has just witnessed a car hit a different boy on a bike, and the adrenaline that runs through her is almost sexual in nature. Williams plays with the similarity between these two types of arousal, showing how they collide and crash into each other like fast cars. “Again,” one of my favorite stories, juxtaposes a radio show about animal slaughter with a snit between a mother and son. Here and elsewhere, Williams uses juxtaposition to point up the violent desires that mothers routinely suppress.

Although Williams has stuck with the formula she found early, her more recent pieces, as Ben Marcus writes in his introduction to The Collected Stories, “took a turn toward the cryptic.” (This is something like saying that late in life Marlon Brando “took a turn toward the brooding.”) The 2012 collection Vicky Swanky Is a Beauty, for example, contains a number of brief, epigrammatic stories—“The Use of Fetishes,” “Weight, Hair, Length,” “Cockeyed”—that refuse interpretation entirely. What to make of the second of these stories, in which a couple admires a bronze sphinx and tries to buy a gilded jug? Williams, usually so adept at sketching a social world in just a few strokes, doesn’t give us quite enough context or atmosphere to show us why these people or objects are significant.

In other late stories, such as “Human Being,” concision can serve as a shortcut to profundity, a way to avoid the hard work of imagining a narrative situation or an idiosyncratic character. These later stories are like carefully fashioned objects, cold and gemlike and a bit too precious. They don’t always adequately do what Williams does best, which is to express the strangeness of human feeling.

This cryptic turn works better when laced with humor. “Oh, Darling I’m in the Garden” is a funnier, weirder rendering of her old adultery material. And some of her stories about aging, such as “The Fucking Lake” and “A Pot Over a Very Low Heat,” are almost poignant. In the latter, a woman describes how she “conjures” her husband, “backlit by her mind’s proprietary light,” so he no longer appears “aged and dedicated to her.” It almost seems that Williams, so often skeptical toward marriage, is depicting something like the endurance of love.

This doesn’t mean that Williams, now in her early seventies, has grown complacent. She is still a restless writer, still committed to revealing all the ugly feelings within the functional person or the happy home. She has always taken as her point of departure that place where most narratives conclude: the wedding ceremony, the birth of a child. She shows how even after reaching a point of resolution, volatility and excitement and uncertainty remain. So often, life doesn’t play out as we think it will. Stories, Williams suggests, should be similarly unpredictable.

“This begins where so many others ended, where the man and his wife are going to live the rest of their entire lives in perfect joy, so they arrive at the train station,” she writes at the beginning of “Clean,” from her second collection. But the train never arrives at the next station. The journey is never over, or it ends prematurely, prompting another adventure, another clause in the sentence, another attempt to represent a feeling that lingers long after the conditions that produced it are lost.