The black-and-white video looks, just for a moment, like it might be a real cooking show. The female host holds up a chalkboard displaying its title, then puts on her apron and picks up a bowl. Yet instead of preparing food, she begins to stir with an invisible spoon. One by one, she picks up kitchen utensils and says their names aloud, making her way through the alphabet—“apron,” “bowl,” “chopper,” “dish,” and so on—until she reaches U and starts spelling out the rest of the letters with her body. She never handles any food.

Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen is one of the artist’s most beloved works. The six-minute video parodies cooking demonstrations, replacing the typical gracious host with, in the artist’s words, “an anti-Julia Child” played by Rosler, who doesn’t smile and maintains a withering stare throughout. The performance is both funny—Rosler delivers the whole thing deadpan, breaking character only slightly at the end to shrug—and full of rage. Rosler uses a familiar form to critique the oppression of women through domesticity, and to subvert the kinds of knowledge and behavior this requires. She swallows her anger long enough to get through the whole alphabet, but the tension is palpable. It hangs in the air—which she slices with a knife as she outlines the letter Z.

Rosler made Semiotics of the Kitchen in 1975, a year after receiving her MFA from the University of California, San Diego. At the time, Southern California was home to a robust feminist art scene: Judy Chicago had established the first feminist art program in the country at Fresno State a few years earlier, and the landmark exhibition Womanhouse took place inside a rundown mansion in Hollywood in 1972. Female creators were embracing and experimenting with the relatively new forms of performance and video, leaving behind the modernist and sexist baggage of painting. Rosler had moved to California from New York City as what she calls “a semi-lapsed painter but also a maker of photographs, photomontages, and a bit of sculpture,” but it wasn’t long before she was performing and recording herself.

Much of Rosler’s art over the course of her more than 50-year career has been concerned with the treatment of women, yet she has gone on to treat other subjects in equal measure. The look and focus of her work have changed often, from video taking apart the media’s endorsement of torture, to photographs of her gentrifying Brooklyn neighborhood, to head-on critiques of President Trump. She’s never developed a “signature style,” as Holland Cotter noted in a 2000 review. This is likely the reason that some critics have found it difficult to clearly define her project. She has not been pigeonholed as a “feminist artist” in the same way that Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, and Carolee Schneemann have. She’s often called a “political artist,” or, less approvingly, a maker of simplistic “activist art,” but these catchall terms are more vague than they are useful.

A new survey of Rosler’s work at the Jewish Museum, titled Irrespective, helps bring into focus the contours of her politics, as it illuminates her urgent curiosity about the workings of society. Gathering samples of a seemingly disparate oeuvre, the exhibition shows Rosler returning to and reexamining the same issues: gender roles, economic class, globalization. Crucially, Irrespective demonstrates how Rosler has adopted feminism not simply as a subject, but as an intellectual and artistic framework. “Feminism is a viewpoint,” she has written, “that demands a rethinking of all structural relations in society.” She has made that rethinking her life’s work, exposing hidden assumptions and attempting to shift our gaze toward the systems we might take for granted. She wants us to see more clearly how the world operates, so that we’ll be better equipped to change it.

It’s rare that an artist starts out making some of their strongest and most enduring work, but that is the case with Rosler; she seems to have emerged with her priorities and talent fully intact. The exhibition acknowledges this by opening with a blown-up, wallpaper version of “Cargo Cult,” a work from Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (c. 1966–72), a photomontage series Rosler started before she moved to California. “Cargo Cult” features magazine pictures of women applying makeup, pasted onto stacked shipping containers in a port. Several men are at work, lifting the containers by crane in order to get them where they need to go. The piece calls out the impossible beauty standards that society imposes upon women, but there’s more going on. The women applying makeup are all white, and the men moving the boxes are black. “Cargo Cult” reminds us that the apex of beauty in the United States is whiteness—a dangerous idea that we are exporting to other countries.

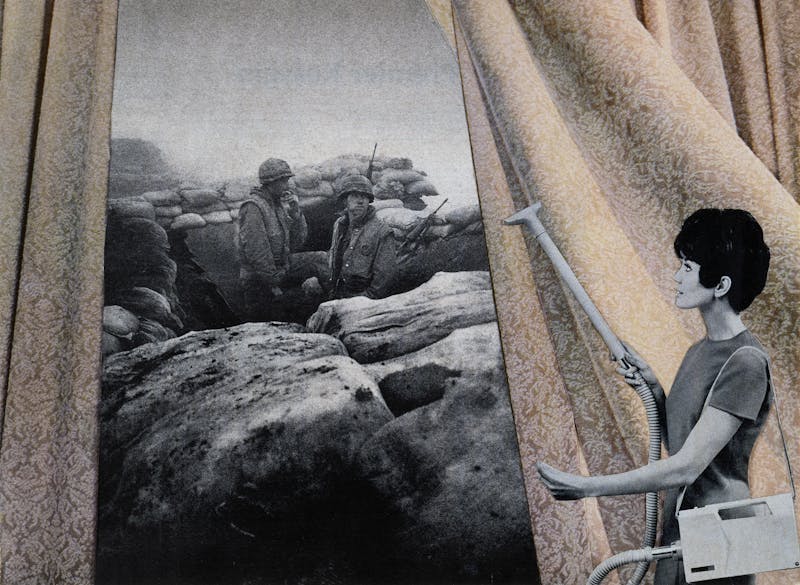

The combination of different pictures is so seamless that it’s jarring. Although you can tell almost immediately that the image must be doctored, it beguilingly retains its formal integrity. Rosler does the same thing to powerful effect in what’s probably her most famous series, House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c. 1967–72). Originally made as flyers that she distributed at Vietnam War protests, the works in House Beautiful combine imagery of the “living room war”—the first conflict that Americans saw unfold on their televisions at home—from Life and other media sources with photographs and advertisements mostly from House Beautiful, an interior-decorating magazine.

One of the images, “Red Stripe Kitchen,” shows two soldiers appearing to search for explosives in a gleaming white modern kitchen; their presence is somehow incongruous and innocuous at the same time. Another, “First Lady (Pat Nixon),” portrays the president’s wife in a stately gold room, where the painting above her head has been replaced by a photograph of a dying woman; her closed eyes and pained expression make for a stark contrast with Nixon’s cheerful smile. In 2003, ’04, and ’08, Rosler made a new set of House Beautiful works in response to America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; rather than feeling like a retread of old material, they’re filled with freshly horrific juxtapositions. In “Photo-Op” (2004), the faux-shocked faces of two blonde models posing with cell phones look especially callous in the presence of two injured or dead children in sleek chairs behind them, while an explosion lights up the sky outside.

House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home captures, at a very early point in her career, the nature of Rosler’s feminism—it was a wide-angle lens, a way of looking out at the rest of the world, as well as an impetus to examine the experiences of women. In contrast to many in the movement around her, Rosler has never seemed especially interested in the plight of middle- and upper-class white women. She instead uses familiar images of them as lures: “Like a wooden decoy duck,” the glossy magazine images draw the eye in, she has explained, but then, “on closer inspection these things turn out to be something other.” The works aim to expose the scaffolding on which normalcy itself is built: The tastefully appointed interiors at home rely on the imperialistic wars abroad more than we might care to admit.

In Body Beautiful and House Beautiful, Rosler is a trenchant media critic. For her, the question of what we know (or think we know) is inextricably bound up with how we’ve learned it. But there’s a limit to the complexity that can be conveyed in photomontages, a form that ultimately relies on many of the same visual principles as the media that it critiques. What happens after you’ve caught the viewer’s eye?

In Rosler’s video A Simple Case for Torture, or How to Sleep at Night (1983), she took a different approach. The work is a response to a Newsweek essay that argued torture is sometimes “morally mandatory.” Over the course of an hour, we see disembodied hands paging through newspaper articles and magazines; they’re punctuated by typewritten key phrases (“lives of the innocents”) and accompanied by jagged bursts of music and voices detailing stories of torture in Latin America. The video is dense, self-reflexive, and makes little appeal to viewers’ emotions. It seems designed to overwhelm us with a barrage of information and push us toward a state of enlightened alienation.

This rigorous, almost dissertation-like approach is another hallmark of Rosler’s practice. But Irrespective also highlights a less familiar and more straightforward method she has used to reach audiences. Her photography series directly present Rosler’s own point of view, in a departure from her use of found images. One gallery groups Ventures Underground (c. 1980–ongoing), In the Place of the Public: Airport Series (1983–ongoing), Rights of Passage (1993–98), and Greenpoint Project (2011). These are intimate pictures shot while riding subways around the world; photographs of gleaming airport interiors; panoramic images of lifeless highways and bridges taken while driving; and pictures and short passages about local businesses in her neighborhood. Many of these works feel diaristic, like private glimpses into the life of an artist who has tended to look outward, rather than in on herself. There are no added layers of mediation, with the exception of the evocative words and phrases (“trace odors of stress and hustle”) that fill the gallery wall to complete In the Place of the Public.

All of this may be why the photographs feel more like process notes than finished products. Yet the series—especially the three about travel—are consistent, in their own way, with Rosler’s project. She interrupts the flow of everyday life to reframe it with a critical eye—to make us pause and consider the spaces we pass through routinely. Staring at stone-faced passengers boxed into metal subway cars and at concrete stretches of highway, she prompts the viewer to think about the harshness of the built environment. When such alienating spaces connect our cities, is it any wonder that many of us struggle to link ourselves personally and politically to others?

Irrespective is an excellent introduction to Rosler’s oeuvre, establishing some of her core concerns. Its weakness is that it’s a relatively small, object-focused show, whereas some of her most exciting and instructive art has been collaborative, public, and even ephemeral. Perhaps most notably, there are the garage sales she held between 1973 and 2012. In each case, she arranged a hodgepodge of secondhand items—underwear, chairs, animal figurines, even bad paintings—and offered them to the public at arbitrary prices. Part-installation, part-performance, the sales commented cleverly on the complicated ways we determine value, bringing items typically thought of as disposable or cheap into art spaces, where objects are expensive and reign supreme.

Rosler has also made powerful interactive work about housing. In 1989, she organized a landmark series of three exhibitions at the Dia Art Foundation under the title If You Lived Here… Each focused on a different aspect of the housing crisis in New York City, and all included work not only from artists but also from community groups and homeless people. She also held four town hall meetings. The project ignored established hierarchies, as Rosler brought art and artists into dialogue with the wider community, in part to point out their role in the process of displacement: Artists moving into a neighborhood often heralds the beginning of rent increases that squeeze current residents. At the same time, she gave the community access to the resources of the art world.

It’s disappointing that these and Rosler’s other socially engaged works are not represented in the galleries at the Jewish Museum, only in the Irrespective catalog. These projects are the most radical manifestation of her approach to political art making. They shift the relationship of artist to audience so that it’s less top-down: Rather than making a video to tell viewers everything she thinks they should know about the housing crisis in New York City, she creates a space where they can go, learn, and ask questions. Rosler becomes an informed facilitator rather than the sole authority.

After all, if the final gallery at the Jewish Museum urges anything, it’s not to trust those with grand claims to authority. The room features two works about President Donald Trump: a digitally distorted compilation of footage from the White House and a print of Trump, overlaid with two sets of text—a comment he made about being able to shoot someone and not lose voters, and the names of people of color who have been killed by the police. The Trump works are the weakest in the show; Rosler hasn’t figured out how to tell us something we don’t know yet. But they share space with two other projects, both about books, and this sets up a clear conceptual battle between the pursuit of truth and a disregard for it.

One of those is Off the Shelf (2008, 2018), a series of digital photomontages of books from Rosler’s library. The volumes are grouped thematically under such titles as “Utopian Science Fiction, F” or “War and Empire” and seem to float within gradient-colored spaces, untethered from any physical reality. The series represents an ideal of the pure transmission of knowledge—one that Rosler attempted to manifest between 2005 and 2009 by actually turning her library into a traveling installation that viewers could browse.

The other is Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century) (2006), which occupies the center of the gallery. Fourteen clear mylar panels hang from the ceiling, each one containing a passage, in German and in English translation, from the political philosopher’s 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism. The work is simple but effective: The panels are hung at odd angles so that viewers may walk between them, immersing themselves in words that feel weighted with moral and emotional clarity. “Intellectual, spiritual, and artistic initiative is as dangerous to totalitarianism as the gangster initiative of the mob, and both are more dangerous than mere political opposition,” it reads, and here we are, face to face with that reality. The work points us back to what Rosler has been telling us all along: Look again, closely, at what you think you know, and don’t doubt the importance of what you find.