On Friday, The Weekly Standard was shuttered by its owners Clarity Media Group, bringing to an end the magazine’s 23-year run as America’s leading neoconservative publication. The news of the journal’s demise raised some pressing questions: Was the closure politically motivated, with a Republican media company wanting to silence a magazine notorious for criticizing the president? Or was this, as some reports indicate, more of a business move, with Clarity planning on harvesting the Standard’s mailing list for its planned launch of a Washington Examiner national magazine?

President Donald Trump, for one, greeted the news with undisguised delight:

The pathetic and dishonest Weekly Standard, run by failed prognosticator Bill Kristol (who, like many others, never had a clue), is flat broke and out of business. Too bad. May it rest in peace!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 15, 2018

Some who don’t share Trump’s politics echoed his dismissal of The Weekly Standard. Harvard international affairs scholar Stephen Walt pointed out the magazine’s disastrous advocacy of the Iraq war:

Seems to me if a magazine proudly lobbied for a disastrous war that cost 1000s of lives & trillions of $, it deserves to go out of biz. Its founders, editors, and chief writers deserve neither our sympathy nor our attention. #WeeklyStandard #accountability

— Stephen Walt (@stephenWalt) December 15, 2018

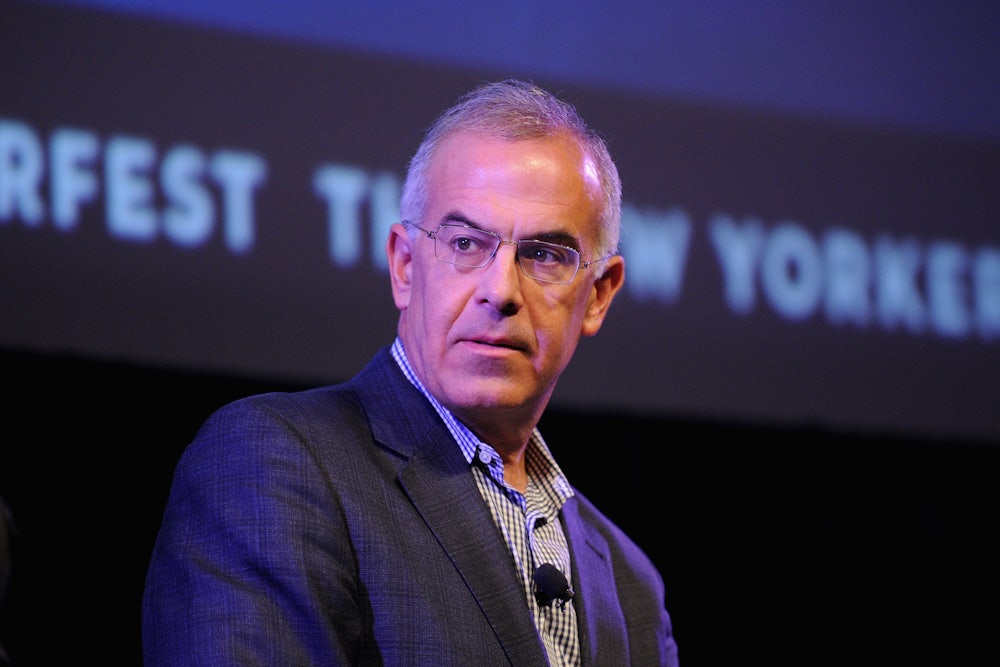

Journalist Glenn Greenwald, mocking a column by former Weekly Standard writer David Brooks, echoed Walt’s argument:

In David Brooks' NYT eulogy of @weeklystandard, the word "Iraq" never appears, even though that war & the horrors that followed is, by far, the most consequential legacy of that magazine. People forget Brooks was one of the most unhinged warmongers there: https://t.co/hPsVku6d6c

— Glenn Greenwald (@ggreenwald) December 16, 2018

The column Greenwald criticized was an unusually angry one from the normally complacent and placid Brooks. The New York Times columnist claimed that, “this is what happens when corporate drones take over an opinion magazine, try to drag it down to their level and then grow angry and resentful when the people at the magazine try to maintain some sense of intellectual standards. This is what happens when people with a populist mind-set decide that an uneducated opinion is of the same value as an educated opinion, that ignorance sells better than learning.”

Brooks’s critique of corporate culture was unexpected, since the conservative columnist is normally loath to criticize capitalism except in the vaguest terms. Brooks described Phil Anschutz, the owner of Clarity, as a “run-of-the-mill arrogant billionaire.” Brooks also added that, “Anschutz, being a professing Christian, decided to close the magazine at the height of the Christmas season, and so cause maximum pain to his former employees and their families.”

The most balanced assessment of The Weekly Standard’s end came from Franklin Foer, writing in The Atlantic. Foer had personal reasons to resent the Standard, since he had been the victim at the hands of The Weekly Standard of what he calls “a bad-faith effort to discredit stories about the war I had published as the editor of The New Republic.”

Still, Foer was able to put his memory of these attacks aside and praise the Standard for publishing, in addition to much neoconservative agitprop, much graceful, well-reported journalism.

“But it’s worth pausing to consider why a magazine like the Standard can be pleasurable and important, even to those who find its goals and methods noxious,” Foer notes. “In part, it’s the spectacle of watching lively minds on an expedition. The Standard would go off on quixotic missions, and not all of them in the desert of Iraq. Kristol promoted Colin Powell as a presidential candidate in 1996; then he cheered on John McCain’s challenge to George W. Bush in 2000. The magazine enjoyed making mischief and enemies, which made its pages highly readable.”