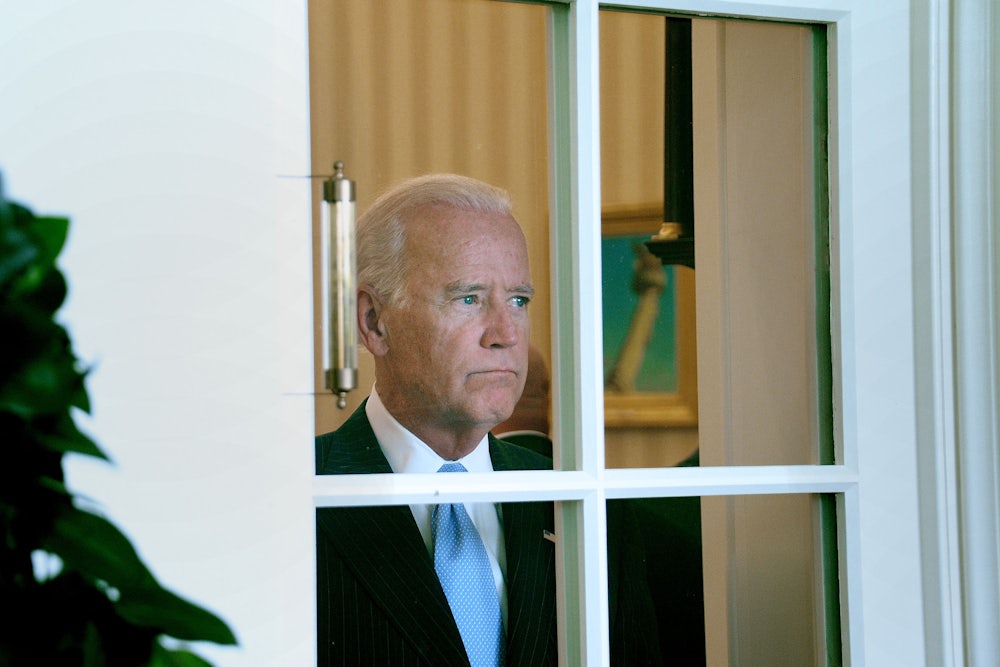

Joe Biden is feeling so good about his 2020 chances, he’s already thinking about a running mate. Last week, the Associated Press reported that Biden’s advisers have discussed the possibility of teaming with a younger candidate—Beto O’Rourke’s name has come up—to fend off concerns about the 76-year-old’s age. With the 2020 Democratic National Convention more than 18 months away, such talk may seem premature. But the early months of 2019 likely will see a glut of Democrats declaring their candidacy, and Biden is poised to begin the race in pole position. He has posted sizable leads in national polling and, over the weekend, led the first poll of likely Iowa caucus-goers by a large margin.

Biden is the early frontrunner for obvious reasons. He served for eight years as the vice president of Barack Obama, the most popular figure in Democratic politics, and did so with an avuncular charm that was once seen as a political liability, but has aged well under a crass president. He is also aided by the sheer size (likely several dozen candidates) and opacity (no major figures have announced their candidacy yet) of the field. He also may be benefitting from not having had any direct involvement in politics since leaving office two years ago; unlike elected Democrats, he hasn’t had to make any difficult decisions or defend his response to the Trump administration. He is, in short, an elder statesman of the party, and is being treated as such.

But these benefits have significant drawbacks, all of which will begin to appear once Biden actually starts running for president, which he is expected to do. Hillary Clinton, after all, was in a very similar position in advance of the 2016 contest, having enjoyed a surge in popularity from her successful stint as President Obama’s secretary of state through her retirement from public office. In 2013, polling suggested she was the most popular politician in America. But reentering politics swiftly changed that: Her favorability plummeted after she announced her race for president in 2015. This is not a perfect comparison, for reasons I’ll explain, but to some degree this happens to all former politicians who rejoin the fray.

We may already have hit peak Biden, and it’s all downhill from here.

Biden’s public image has been bolstered by his distance from public life. Even as vice president, he largely kept his hands clean of everyday politics in Washington. If Obama was seen as the brain of the administration, Biden was its heart and soul: an emotional man of the people, simultaneously macho and unafraid to cry in public, who famously pressured Obama (albeit accidentally) into supporting gay marriage. That perception has only grown in his retirement, as Trump’s rise has fueled a nostalgia for more decent times in American politics.

But if Biden runs, his past will be raked over—and his political record looks increasingly checkered in today’s light.

Biden shamefully failed to protect Anita Hill after she accused Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment in 1991. He refused to call corroborating witnesses and did nothing to block disgusting personal attacks from Republicans. This was already seen as a weakness in the #MeToo era, but has become even more damaging after Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings. (Biden has made things worse by failing to apologize to Hill.) Republicans, particularly Trump, will make much of Biden’s handsiness, but his treatment of Hill is by far his biggest liability.

Biden’s legislative record also contains a series of blights. As a representative of Delaware, one of America’s most corrupt states, Biden is notoriously cosy with financial interests. He spent years advocating for a law that made it significantly more difficult for consumers to declare bankruptcy, before it finally passed in 2005. Elizabeth Warren called it an “awful bill” and support for it likely hurt Hillary Clinton when she ran for president in 2016. Like Clinton, Biden supported the Iraq War and the 1994 crime bill, which made mass incarceration significantly worse. Unlike Clinton, Biden still defends the crime bill, which he praised in his 2017 memoir, Promise Me, Dad. If critics were to dig even further into Biden’s past, they would find that he went to great efforts to suppress busing and other school integration efforts and was against reproductive rights before he was in favor of them.

Biden, if he runs, undoubtedly will argue that he is the only Democrat who can truly connect with the white, blue-collar voters who have fled the party in recent years. He has always reveled in the perception that he’s an authentic politician who understands the so-called common man in ways that his colleagues do not. Even one of his greatest political weaknesses—his penchant for gaffes—can be favorably spun: He’s a guy who says what he thinks, and that worked out pretty well for Trump, didn’t it?

In Promise Me, Dad, Biden shows that he’s not inflexible, making the case that, had he run for president in 2016, he would have ended tax breaks for the wealthy and advocated for a $15 minimum wage. His laudable decision to turn down a $38 million speaking deal also suggests that he can read the political winds. But in a primary that may revolve around Medicare for All and a Green New Deal, Biden’s obvious centrism and voting record will be liabilities that his off-the-cuff style may make worse—it’s easy to imagine the punchy, impulsive Biden doubling down when he should be recanting. At the same time, reminders of Biden’s past stances and behavior will damage the kindly Uncle Joe image he’s cultivated over the past decade.

A Biden candidacy, like Clinton’s, would serve as a reminder of the many flaws of a party establishment that an increasing number of Democrats would like to overthrow (or at least overhaul). But there are some important differences between Biden’s situation, if he runs, and Clinton’s. Biden doesn’t have the same exaggerated scandals in his closet that Clinton did. He also won’t face a sexist backlash. And perhaps most important, Biden would enter the race as the frontrunner, but not the presumptive nominee. Clinton really only had to fend off a single challenger, a septuagenarian democratic-socialist who rarely even identifies as a Democrat. Biden will have to beat out as many as 34 candidates for the nomination. The odds are simply much worse.