When does a movement become a Movement?

It is a vexing question. Invoking the term is meant to denote seriousness, to suggest that the activism you are engaged in will not disappear with the passing of the news cycle or be headed off by the most recent tidbit of celebrity gossip. A movement digs deep, plants roots, and grows until its objectives are achieved. There are today no agreed-upon benchmarks to be reached in order to call something a movement: No law must be passed, no number of people assembled in the public square. Anyone with a cause can claim the term in order to benefit from the gravity it connotes. With such a low barrier to entry, it becomes harder for even the most benevolent social critics to distinguish “thoughtful networks of dissent built over time,” as the historian Blair L.M. Kelley defines a movement, from those that are branded as such without any effort to be one.

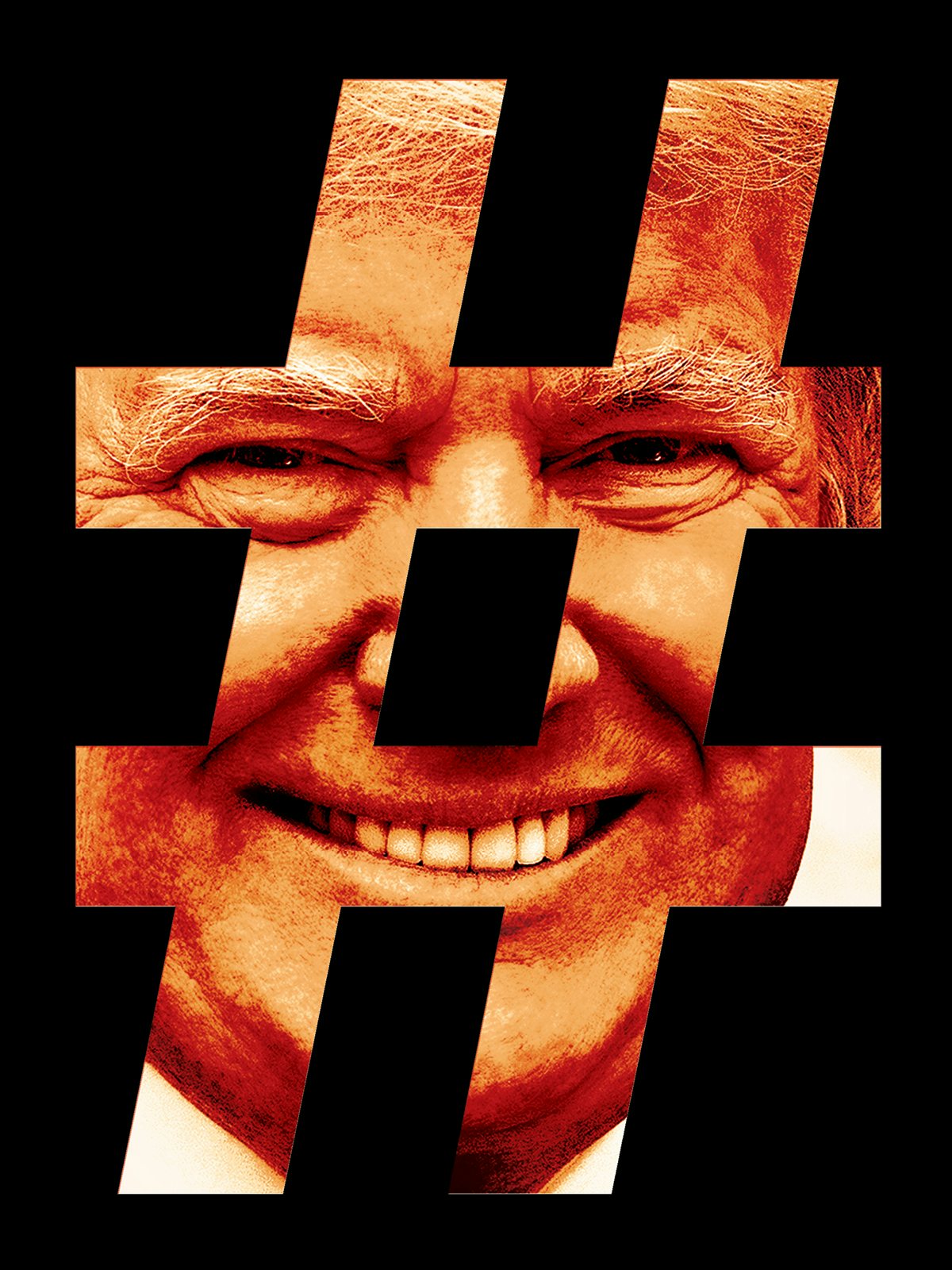

The Resistance, the ubiquitous term for all manner of anti-Trump activity, emotion, and intention, came into being shortly after election night in 2016. This was a bitter moment for any American who until then had believed that the historical arc of the country bent toward progress. The presidential election presented a stark choice, between the first woman president and a “short-fingered vulgarian” with a long history of saying—and doing—openly racist and sexist things. Donald Trump was a symbol of an ugly past that had to be overcome, and embodied a rancorous desire to grasp those old “truths,” as was evident in his campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again.” In Hillary Clinton, Americans devoted to progress had placed their hope for the future, some begrudgingly, others enthusiastically. They were greatly disappointed.

Two years on, it remains self-evident that the Trump presidency poses a grave threat to democracy, nonwhite people, and even our ability as human beings to inhabit the planet. It remains equally apparent that there is a collective responsibility to resist—him, his supporters, what they mean, what they want—though what shape that resistance should take, and what demands it places on those who partake in it, are less apparent. The Resistance—capitalized into a movement—was supposed to answer that. It should be a source of power in contending with Trump’s destructive agenda. Instead it has been little more than a tool, a form of branding, for the most benign type of opposition, trading on the radical resonance of the word “resistance” in order to appear more powerful than it actually is. The Resistance is a movement in the sense that those who have taken up its banner call it a movement, but no more than that. It is a movement because it is rather than because it does.

Perhaps it’s unfair to ask the Resistance to be anything more than that. It may, charitably, be best understood as a social media campaign rather than a movement. If that is so, it may even have been effective. Movements require organizing on a grand scale—of people, money, and other resources—to wage effective legal challenges, coordinate direct action, politically educate newcomers, and build institutions. The Resistance has not produced any of those things. Or rather, it has not produced these movement hallmarks within the context of the Resistance as a movement unto itself. What it has done is given people a slogan under which they can rally. It has allowed them to find others who are frustrated, isolated, and afraid. It has raised awareness and kept people informed about some of the most pressing issues of this still young presidency. That’s worth something.

Joining the Resistance, as political historian Beverly Gage put it in The New York Times a year ago, does not “require adherence to any particular ideology or set of tactical preferences. It simply means, in the biggest of big-tent formulations, that you really don’t like Donald Trump, and you’re willing to do something about it.” A coalition that simple, formed around a shared dislike of a single person, has one upside: numbers. Donald Trump is a historically unpopular president who badly lost the popular vote. The tent is large.

The problem with a coalition of that sort is not everyone thinks they are in the same one. Trump has created enemies of all political stripes—anarchists, socialists, liberals, and a fair number of conservatives. The only groups he has not alienated are white evangelicals and alt-right neo-Nazis. In this way, he is a “uniter.” But unity is overvalued in movements, as it matters more what you are uniting around and whether you act in solidarity. With so many competing viewpoints, solidarity within the Resistance is essentially impossible to achieve, and really seems to be beside the point.

Still, the Resistance does have an apparently left-wing bent. People on the left were the ones most dismayed by Trump’s victory, and who initially claimed the mantle of Resistance. But the thirst for more resisters has meant welcoming anyone with even an incidentally critical thing to say about Trump. David Frum and Bill Kristol are friends of the Resistance. George W. Bush is in the Resistance. (He’s not.) Omarosa Manigault Newman, a former assistant to the president as well as former contestant on his reality game show, was greeted by the Resistance when she exited the White House. Fired FBI Director James Comey “joined” the Resistance because he took notes on conversations he had with Trump that could potentially be incriminating. It mattered little that Comey was at least in part responsible for Trump’s election, or that he was a longtime member of an institution responsible for violating the civil liberties of activists and marginalized people. It’s the type of thinking that led The New Yorker to declare John McCain’s funeral “the biggest resistance meeting yet.” The Resistance has embraced anyone with the temerity to speak against the president. That is all. But it is not enough.

This would seem to be by design. The objection to Trump is based less on his policy positions than on his personality. That is, while there has been opposition to the most odious parts of his political agenda, what has truly animated the Resistance is disdain for Trump’s character. He is a bully who insults and condescends to people with whom he disagrees, or who insufficiently praise him. He lies, blatantly and frequently, in a way that is either pathological or part of a convoluted strategy for manipulating the truth. He speaks in incoherent sentence fragments and never resists an opportunity to brag, even when his self-adulation is based on partial or complete falsehoods. Trump is, in short, not presidential.

He is so unpresidential that when he meets the minimum requirements of decency, he is praised as if he has done something consequential. When he addressed a joint session of Congress early in his presidency, he managed to read his prepared speech from a teleprompter without the bluster that characterized his campaign rallies or press conferences, and at one point honored the wife of a slain Navy seal. “He became president of the United States in that moment, period,” CNN’s Van Jones declared. No matter that the speech contained outright falsehoods about immigration, crime, welfare, the federal budget, and that it overstated the impact the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines would have on job creation (not to mention the disastrous environmental impact and displacement of indigenous people). What mattered was his presentation. Trump briefly sounded like a president. That should not have been enough. But for a moment it was.

The Resistance is not about whether one agrees or disagrees with Trump on the issues, whatever those may be. It is not about policy. It is about the threat that Trump poses to the idea of progress, the comforting notion, entrenched by the election of Barack Obama, that things in this country could get better without anyone having to give anything up to make that so. When Trump refuses to denounce white supremacist groups that have endorsed him, the issue becomes less that his beliefs line up with theirs, and more that he has not rhetorically separated himself from avowed white supremacists. It becomes embarrassing to witness him on a global stage push past other world leaders so that he can be in front of a photo-op. His sophomoric speaking style is far below the level of what presidents are supposed to be able to employ. He watches television compulsively and live tweets his favorite Fox News shows. He refuses to release his tax returns to be reviewed by the American people. He is deeply incurious and proudly so, refusing to sit for traditional presidential briefs or to read anything that doesn’t mention him by name. During a ceremony to reintroduce the National Space Council, he responded to Buzz Aldrin’s sarcastic exclamation of “Infinity and beyond!” by saying, “It could be infinity. We don’t really don’t know. But it could be. It has to be something—but it could be infinity, right?”

It’s not good to have someone with so little interest in knowledge as president, someone who flaunts his ignorance as a badge of populist pride. And that is the dilemma the Resistance faces in exercising any meaningful political power. Trump has defied the norms and expectations of the presidency, and American politics more generally, and succeeded. The Resistance has made heroes of those who have pointed this out. But it has not questioned the basic nature of the presidency, or the country. It is dangerous to believe there is some victory in removing one person from an oppressive system while leaving the system intact. This is a dynamic the Resistance has shown no interest in addressing. Until it does, it can never be a movement.

There is a gross underestimation of how norms produced the Trump presidency. The Electoral College is an American norm. Placating racist voters is the norm, and cuts across both parties. Distrust and disdain for women in positions of power is the norm. Executive orders that overstep the constitutional powers granted to the presidency are now the norm. Some norms need to be challenged. America’s liberals have only been willing to challenge them to the extent that they do not uncomfortably burden its ruling classes with drastic calls for change. The Resistance has reflected that stance. It is the major impediment to consolidating this would-be movement around an agenda worth fighting for. Even if the principal objective is the removal of Trump from office, what drives that cannot be a desire for a return to what was once defined as normal. That would only set the stage for another Trump to rise. The goal has to be a complete reconsideration of the American system of governance.

Resistance is a reactive state of mind,” Michelle Alexander wrote in The New York Times. “While it can be necessary for survival and to prevent catastrophic harm, it can also tempt us to set our sights too low and to restrict our field of vision to the next election cycle, leading us to forget our ultimate purpose and place in history.” Viewed this way, the word resistance itself provides the wrong framework for understanding what must be done. James Baldwin refused to say the “Civil Rights Movement” because it was a term applied by white media onlookers. He instead referred to the period of heightened activism in the 1950s and ’60s as the “latest slave rebellion.” The contrast in meaning is stark. The enslaved possess no rights to be protected, only a system of dehumanization and exploitation to rebel against. Phrasing it this way captures a very different, very dire political terrain, one that requires a higher level of militancy to effectively counter.

The Resistance is something else entirely. Its active distancing from militancy reveals as much. On January 20, 2017, the day of Trump’s inauguration, thousands of protesters in Washington, D.C., took part in a different kind of demonstration than the one that would follow the next day during the Women’s March. Two hundred and thirty-four people would be arrested and face charges including felony inciting to riot, conspiracy to riot, rioting, and destruction of property. The J20 march, as it came to be known, was not just anti-Trump but anti-capitalist and anti-fascist. Its participants left a trail of thrown objects and smashed windows. Police teargassed and arrested them.

These protesters were roundly denounced by those who supported the next day’s events. Indeed, the virtual absence of arrests among the estimated 500,000 to one million people at the Women’s March in D.C. (or among demonstrators at any of the other sites across the country) the next day was heralded as a sign of its success. These were peaceful participants in democratic action, unlike the rabble-rousers of J20.

There is something immensely powerful about orchestrating the largest single-day march in the history of this country, as the Women’s March is believed to be. Many of its participants had previously never attended a march or thought of themselves as actively political. But there is also something shortsighted about not simultaneously embracing the J20 protesters. Those repelled by their tactics see only destruction and chaos, rather than the inevitable direct confrontation of state power—inevitable if there is a goal past the removal of Trump. The two years of his presidency have shown that he is a uniquely dangerous president, but his ascent was made possible by entrenched interests that predate him. He is only the latest representative.

Confrontational resistance is justified because conventional processes can only do so much to mitigate harm. Voting, in particular, is effective only to the point that it is understood that the citizenry will forcefully dissent from governance if its will is not honored. But it must also be understood that the problems Trump represents do not only exist at the state level. What is now called the “alt-right” has been organizing itself, in the shadows, for decades. Its adherents have developed alternative information channels, formed online communities, adopted a common language, and mobilized in ways that have found a home in the Republican Party.

Their agenda is best understood in the simplest terms: white supremacy. And yet they have been treated with an inordinate amount of benign curiosity, as if they present some fresh ideological viewpoint worthy of consideration in what is, in name, a multiracial democracy. Profiles of their supposedly dapper media leaders have portrayed them as fairly innocuous.

But as the killing of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville in August 2017 showed, the violence of white supremacy is both broader and deeper than the apparatus of the state under Trump. The young men photographed clad in polos and khakis, carrying torches and yelling “Jews will not replace us!” are not minor actors in a political game. They are a vicious threat.

The Resistance has not settled on an adequate response to this threat. Months before Heyer was killed, the alt-right provocateur Richard Spencer made headlines, not for his inflammatory rhetoric, but for being the subject of a viral video in which an antifa activist punched him in the face. The violence was decried, in some circles, as the wrong approach to his growing influence. It was also suggested by some liberal voices that other tactics, like protesting paid speaking engagements for the likes of Milo Yiannopoulos and Steve Bannon, were also outside the bounds of civility and proper discourse. Better to expose their ideas and debate them with a superior vision of an American future.

This misjudges the extent of their appeal, the composition of their threat, and naively places faith in the American populace that it will reject nativist, xenophobic, racist ideologies for their core maliciousness. There is less progress on that front than many would like to believe.

It also presumes that alt-right white supremacists can be somehow shamed into receding from public life or driven from it by force of argument. But no simple denunciation is capable of producing the level of shame needed to elicit the desired effect. Nor is the political terrain conducive to the task. Nonviolent protest, aside from its moral dimensions, has been successful as a tactic because the imagery of the violence it seeks to provoke has had the ability to shame those in power on a global scale. In the United States, however, that was most effective when there was a competing global superpower that could exploit discord within the country as propaganda in an anti-U.S. crusade. With America’s current hegemony, there is little that can be done to shame our leaders, and the grassroots of the alt-right are no different. When confronting people who gleefully rip children away from their families and place them in cages at the border, under the guise of criminality but actually in an effort to establish a white ethnonationalist state, shame, as strategy, fails.

The Resistance has had its greatest success in elections. There have been meaningful defeats of Republican candidates in key races. The first came against Roy Moore in the December 2017 special election in Alabama to fill then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions’s vacated Senate seat. Democratic nominee Doug Jones was able to beat the Trump-endorsed candidate, due in part to multiple allegations of sexual assault against Moore, including that he had improper relationships with minors. As narrow a victory as it was, it nonetheless counted and served as an important signal that Democrats could win contests outside their traditional strongholds.

But the party has had to contend with the split that showed itself during the 2016 presidential campaign. Senator Bernie Sanders mounted an impressive campaign that tapped into the concerns of many young people, and reflected a potentially far-reaching ideological shift. Yet the Democratic establishment, and cautious party members, nominated Hillary Clinton, who ultimately lost. Sanders’s success, and Clinton’s failure, were clear signs to those on the left that their time had come. The reluctance of party officials to concur has frustrated those who feel the Democratic Party, as currently constructed, cedes too much ground to Republicans and cannot serve as an effective opposition against Trump. When Maxine Waters, one of the president’s most boisterous critics, voiced her agreement with activists disrupting Trump officials’ everyday activities, such as eating dinner in a public restaurant, Senator Chuck Schumer denounced the idea from the floor of the Senate, saying, “I strongly disagree with those who advocate harassing folks if they don’t agree with you…. If you disagree with a politician, organize your fellow citizens to action and vote them out of office. But no one should call for the harassment of political opponents. That’s not right. That’s not American.”

Any real resistance would understand that the party ostensibly on its side has done little to advance its agenda, even within the narrow scope of defeating Trump. And yet, experienced, centrist Democrats are still viewed by many within the party as best equipped to lead, at least in the near term. They haven’t given anyone any reason to believe they are.

The surprise primary win in June of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez over the incumbent Joe Crowley in New York’s 14th Congressional District was the first sign from within the party that big changes could be afoot. Ocasio-Cortez received little press attention before her win, and ran as a member of the newly reinvigorated Democratic Socialists of America.

Still, it would be easy to overreact to this single win. Ocasio-Cortez prevailed in a blue district and faced an opponent who did not take her seriously enough. She was shocked by her victory on election night. But the midterms in November delivered exactly what her win seemed to portend: a wave of Democratic victories that consisted of important demographic shifts toward electing women of color who situate themselves in the left flank of the party.

For all the celebration of this development, it is far from certain that the party establishment will adjust course. The drug of bipartisanship is difficult to kick. “Finding common ground” might have seemed reasonable before Trump, although the agenda of the Republican Party has been practically the same for the past 40 years. But now a new question must be raised: What about white nationalism do Democrats think is worth negotiating?

The Resistance, if it is a movement, cannot be too preoccupied with the Democratic Party as an arm of its organization. Institutions as old as the party are primarily concerned with survival. The extent to which the Democrats can be pushed in any given direction will be determined by whether or not they fear a mass exodus from their ranks. With no viable alternative party available to liberal and left-leaning voters, there is no reason to believe such an egress will happen.

The Resistance will have to ask something more of the people who have taken it up. There is a politics beyond that which created Trump. There are labor strikes, sit-ins, boycotts, and, yes, smashed windows and Nazi punching. But if it is to persuade a meaningful number of people to consent to such tactics, much less adopt them, the Resistance has to show itself as a true movement, one worthy of the name it carries and more meaningful to the people who are participating. It needs to find a definition and purpose beyond Trump.

And when those goals have been identified, the Resistance needs to settle in for the drudgery of movement work. It has to accept that this is a fight longer and more difficult than a presidential term, even two. The Resistance can be more than what it has shown thus far. It can be the very political movement that saves America from itself. If it wants to be.