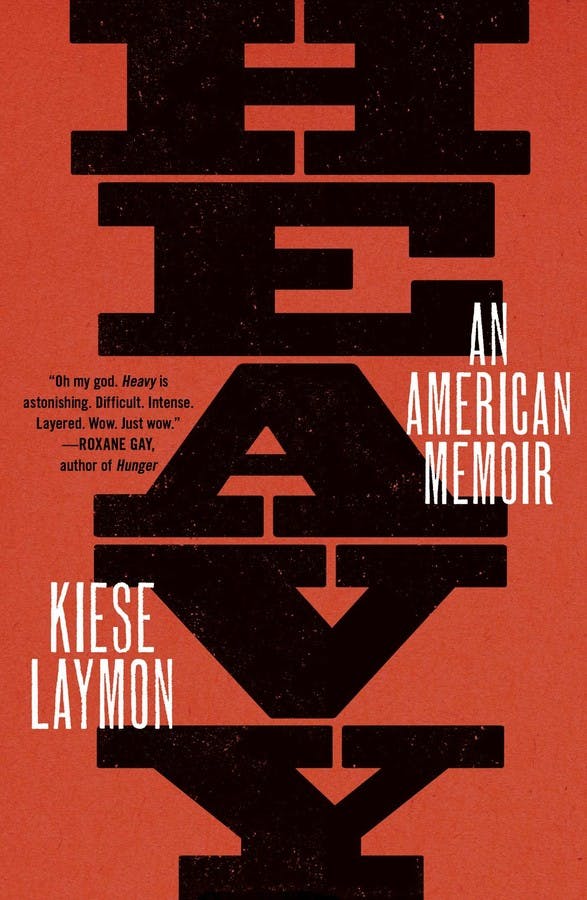

Early in his memoir Heavy, Kiese Laymon writes, “My body knew things my mouth and my mind couldn’t, maybe wouldn’t, express.” It knew that blue cheese dressing made him feel better after awkward interactions with teenage girls, and so did pear preserves and wine when he couldn’t understand the relationship between his mother and another man. But his body also deprived itself of cornbread, collard greens, and butter pecan ice cream because weight loss is tied to memory and instinct. His weight is the visible proof that his body is retaining something.

There is, for one thing, the weight of being a black boy from Mississippi and grappling with the legacy of generations-long disenfranchisement. Just how far can a black boy and his body travel without being reminded of the past? Laymon travels from Jackson to Millsaps College to Vassar College and no matter where he goes, the past is close to the surface. As the decades pass, Laymon’s weight fluctuates and he connects these changes with what’s happening in both the professional and personal realms of his life. In childhood, he is severely overweight. As a young adult, he begins to lose weight. A young man, living and working at an elite private institution, he loses even more. And then the weight returns—as well as the shame. He writes to his mother, “I will weigh myself again. I will cry at the number that I see. I will continue to hide behind podiums, lecterns, huge camouflage, shorts, and black sweatshirts. I will listen to you talk about addiction.”

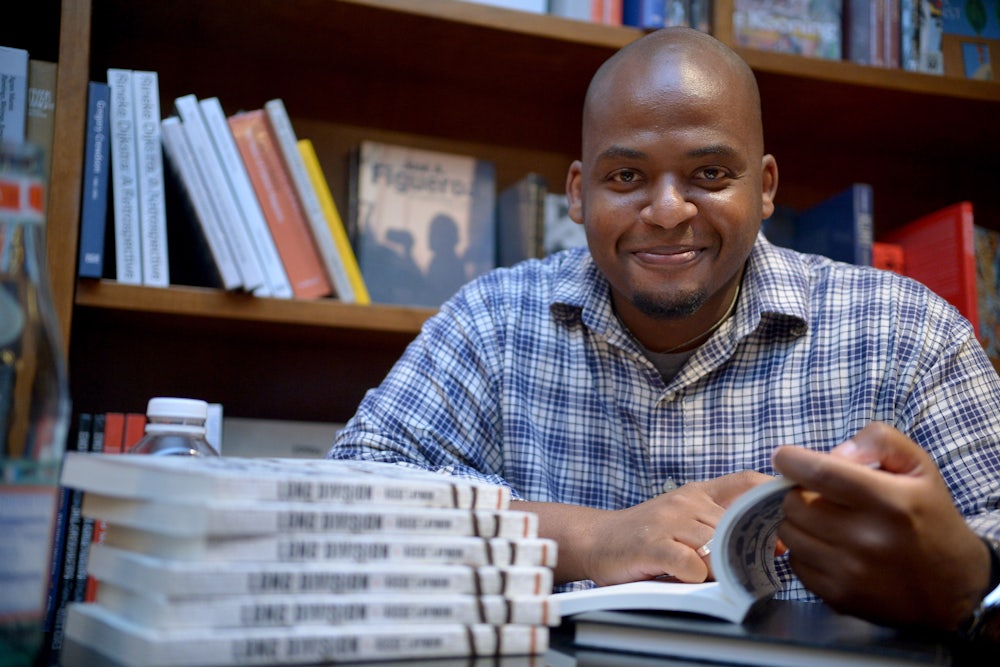

Over the past decade, Laymon, a professor of English at Vassar, has established himself as an accomplished writer: He is the author of a novel, Long Division, and an essay collection, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. Over the years, he has written pieces for The Paris Review, Guernica, and BuzzFeed, among many others. He has studied violence, racism, academia, and white people with laser-sharp focus and rapier-like prose. Now, he magnifies himself almost excruciatingly. His book explores consumption—how it illuminates the secrets and unanswered questions of one particular black man from Mississippi, and how his body has come under threat either from food or systemic racism, or both.

Like James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, Heavy takes the form of a letter. Addressing his mother and grandmother, the two most important people in his life, Laymon writes a confession: “I did not want to write you. I wanted to write a lie.” Laymon implies that secrets were commonplace in his family. Arguably, secrets protected him, but he knows they won’t let him write the kind of book that he is writing now. They have to be purged through honesty.

Laymon starts his story when he is a 12-year-old boy who weighs 213 pounds. His mother, an educator, instructs him to speak the Queen’s English and write book reports on politicians. Laymon follows his mother’s instructions, but he’s more focused on getting near his crush Layla who will be at a nearby swimming pool. All Layla wants to do is float in the deep end of the pool but that desire comes with a price: she has to allow the other teenage boys to run a train on her first. After Layla asks Kiese to accompany her to the pool, Kiese notices something is wrong with her, as it is with him but no one can say what. There’s no resolution to this scene. We don’t know if Layla is ever satisfied in Kiese accompanying her. We don’t know whatever happens to those guys. This is the point—to show how sex and violence can become an almost unremarked feature of daily life.

All the while, Kiese is losing focus on his assignments. When his mother confronts him, he asks if she can help him lose weight. He writes, “I stood there watching you, feeling a lot about what it meant to be a healthy, safe black boy in Mississippi, and wondering why folk never talked about what was needed to keep black girls healthy and safe.” He does not tell his mother why he’s so distracted, but his experience of witnessing harm is a current that courses through the entire book.

The harm Laymon writes about can also be intergenerational. Kiese’s mother often uses corporal punishment. But she is also abused herself. During a twice-a-week therapy session, she professes her concern that Kiese is eating and drinking things that he shouldn’t be whenever he’s angered and Kiese responds, “I drank Mason jars of box wine three times when there wasn’t anything else to eat or drink because it’s sweeter than water.” His biological father is out of the picture, and Malachi, his mother’s boyfriend, is both abusive and erratic in his love and attention. When his mother and Malachi make love—loudly and vigorously—Kiese gorges upon sweets and more boxed wine, which leaves him so inebriated that he cannot finish his report on Fannie Lou Hamer. The physical evidence of this difficult relationship with his mother—in which so much is left unsaid—is that Kiese weighs almost 300 pounds before he graduates from high school.

Once Kiese enters Millsaps College, a private liberal arts institution in Jackson, he seeks to leave behind the safety net of eating, and he forsakes meat, eggs, bread, and sugar. He loses over 70 pounds in a single summer. He forms a relationship with a co-ed named Nzola, though they’re often divided by the ways they each grapple with racism on campus. She wants him to understand the gravity of misogynoir and he says that he does; however, he does not broadcast the issue when the press reaches out to him about the tensions at the institution. Nzola also abuses Kiese, often punching him in the face. Just at the moment when Kiese is starting to love his body, another person assaults it—because they are both suffering under the weight of institutionalized oppression.

In both his account of Nzola’s violence and Malachi’s, Laymon strikes a very delicate balance. He addresses intimate violence but immediately places both situations in the wider context of cycles and patterns of abuse: “We hated where we were. We hated ourselves. We hated fighting, fucking, fighting, fucking, fighting over who was most violated by a spiteful college president, confused white classmates, and the gated institution we paid to attend.” He does not label himself as a victim, a choice that may seem controversial for some. He’s not holding either Malachi or Nzola accountable and calling them abusers outright, perhaps because he is still working with his traumatic memories. His reassessment of abuse is an exploration of feelings and motives from both parties as well as the systems that affect them both.

By the time Kiese makes it out of Mississippi, transferring to Vassar College to become an adjunct professor, he is 180 pounds with six percent fat. From the outside, Kiese has made it, not only achieving excellence through academia but also a high degree of control over his body, his eating, and his image. But he still has responsibilities and ties to home that weigh on him. When his mom calls him with the distressing news that his grandmother has been a victim of theft, he intensifies his workout, running 23 miles in a single night. He gets down to 159 pounds, the smallest he’s been since grade school. The running is meant to help him move on from his insecurities: “Controlling that number on the scale, more than writing a story or essay or feeling loved or making money or having sex, made me feel less gross, and most abundant. Losing weight helped me forget.”

Yet this proves a fool’s errand. His sense of abandonment resurfaces. Is he troubled by the absence of his father? Is he triggered by the fact that his mother doesn’t understand his struggles at various stages of his life? He leaves it ambiguous. Instead, he tell us that he gains weight again. He eats honey buns and cheese sticks. He learns that he has herniated discs, abnormal cell growth, and scar tissue in his left ankle and knee. The weight of family, excessive eating and drinking, and secrets tied to violence had finally taken a toll on his thirty-something-year-old body.

Toward the end of the memoir, Kiese turns from his own experience to reflections on the victims of police brutality, such as Korryn Gaines and Tamir Rice: “I will not buy a gun because I know I will use it. I will watch them murder Tamir Rice’s body for using his imagination outside….I will watch them murder Korryn Gaines’s body for using her voice and a gun to defend her five-year-old black child from America.” It’s a sharp pivot, as the majority of the book is devoted with laserlike focus to Kiese and his own body.

At first glance, the comparisons may seem tacked-on or belabored. After all, the memoir is about Laymon but his message is much larger. He’s not just writing to his mother and revealing himself to her. He’s also writing about his former and younger self, and bearing in mind of all the younger black people out there when he vows:

I will love myself enough to be honest when I fail at loving. I will accept that black children will not recover from economic inequality, housing discrimination, sexual violence, heteropatriarchy, mass incarceration, mass evictions, and parental abuse. I will accept that black children are all worthy of the most abundant, patient, responsible kind of love and liberation this world has ever created.

Heavy is not only a memoir but an exorcism of deeply embedded pains, and of missed opportunities to address those pains when they were inflicted. “There will always be scars on, and in, my body from where you harmed me,” he writes to his mother. “You will always have scars on, and in, your body from where we harmed you. You and I have nothing and everything to be ashamed of, but I am no longer ashamed of this heavy black body you helped create.”

These lines are only few of the book’s many memorable and incredibly moving passages. Heavy is a nourishing, high-caloric book that is not meant to be consumed quickly. It is slow-paced, requiring one to savor each page. This is the portrait of a man who has lived and is not afraid to recognize his mistakes as well as those of other people. The particular kind of black male vulnerability Kiese Laymon has expressed is vital in our literary canon, and it should inspire others to follow.