After months spent teasing his supporters and the political media, Beto O’Rourke surprised absolutely no one Thursday when he officially announced his candidacy for president. “We are truly now more than ever the last great hope of Earth,” he said in a video posted on social media, channeling The Lord of the Rings. “At this moment of maximum peril, and maximum potential, let’s show ourselves and those who will succeed us in this great country just who we are and what we can do.”

These are exactly the kind of empty platitudes we have come to expect from O’Rourke since last year, when his failed, but lively challenge of Senator Ted Cruz turned him from a back-bench, three-term congressman to a national figure (and former congressman). Some have compared him to Barack Obama, with whom he shares a message of optimism and unity. But the comparisons end there. He has all of Obama’s self-assurance with none of his intellectual fortitude, inspirational biography, or oratory power. His rhetoric is as empty as his platform, his paeans to “coming together” the stuff of Obama fanfic.

O’Rourke’s claim to the presidency is based solely on the frenzy surrounding his campaign to unseat Cruz. Over four magical months in the late summer and early fall, O’Rourke made Democrats believe that Texas—which has not had a Democratic senator in a generation—could turn blue. He visited every county in the state, regularly drawing crowds of 50,000 fans, with a message engineered to appeal to both progressives and moderates. “You cannot be too much of a Republican, you can’t be too blue of a Democrat, too much of an independent. You can’t be in prison for too many years, you can’t be too undocumented to be worth fighting for. It is for everyone,” O’Rourke said a campaign stop in Dallas.

It helped his case that Ted Cruz is the most hated man in the Senate. O’Rourke lost anyway, a defeat that looked assured by mid-October. Even O’Rourke seemed to realize it, pivoting his already wide-angled campaign toward increasingly national issues. Many believed that once the midterms were in the rearview, and with his days numbered in the House, O’Rourke would announce his 2020 bid in short order. Instead, he blogged.

Beginning shortly after his loss in November, O’Rourke began posting long, rambling, solipsistic posts on Medium, detailing both his post-election melancholy (“Have been stuck lately. In and out of a funk”) and his continued ability to connect with voters. “What followed was one of these transcendent moments in public life,” he wrote following an event at a Colorado community college. “Something so raw and honest that you want to hold on to it, remember every word … a flow between people.”

O’Rourke’s posts resemble sophomoric creative nonfiction. They’re maudlin, confusing the expression of emotion with profundity. They’re formless, written in a quasi-literary clipped style. And they’re self-serious, filled with banal observations about the experiences that characterize American political life. But these sketches are also littered with stump-speech cliches. In a January, he wrote this entry about a motel owner he met while traveling through Kansas:

I stayed at the Motel Safari, one of these classic Route 66 motels. Mid-century everything. I talked to the owner for a bit. He moved from Tennessee and away from corporate life. Starting over. Giving himself to this hotel that he bought a couple years back. Hasn’t taken a break in more than a year, but is going to close down for the month of February, spend some time back in Tennessee. Take a break, come back stronger.

It’s a clever little paragraph. O’Rourke, ever possessive of a retail politician’s full arsenal, draws out a man’s life story—and seems to be suggesting a parallel with his own. The hard work and struggle of owning a small business in America is not, ultimately, that different than being one of the two or three most popular young Democrats in the country. They both need breaks. They both come back stronger.

O’Rourke catalogued his post-election in other, less bathetic ways. He filmed Instagram live videos of himself eating chips and guacamole in the car, making slime with his children, and even getting a dental cleaning. He skateboarded across a stage, air-drummed in a Whataburger parking lot, never letting people forget he was once in a punk band. An uncool person’s idea of what a cool person is, O’Rourke nevertheless was having fun. If his blog persona resembles a lonely emo teen who just wants the world to see their genius, his video persona is closer to the learned stoner jocks of Richard Linklater’s films. But they have one thing in common: a desperation for attention.

And I haven’t even mentioned his meticulous cultivation of suspense over whether he would run for president. He met with Obama less than two weeks after his midterm loss. He took a campaign-style road trip through the Southwest. He was interviewed by Oprah in Times Square alongside Michael B. Jordan and Bradley Cooper, telling her he would reach a decision by the end of the month. He attended the South by Southwest preview of a documentary about his failed Senate run, Running with Beto. All the while, his team tantalized his supporters. “If you’re on the edge of your seat about Beto’s decision around a potential 2020 run for president, you’re not alone,” read one email sent after his appearance at South by Southwest. “There’s been an outpouring of speculation, excitement, and support from people across the country—everyone eagerly waiting for the news.”

But the way to get people excited about a presidential candidacy is to be an exciting presidential candidate—not to bait them about a potential run for months. America was tiring of his act: He began slipping in the presidential polls. Perhaps sensing he could drag this out no longer, he announced in late February that he had made a decision, and … well, he’d reveal it at some point in the near future.

Then he dragged it out for another two weeks.

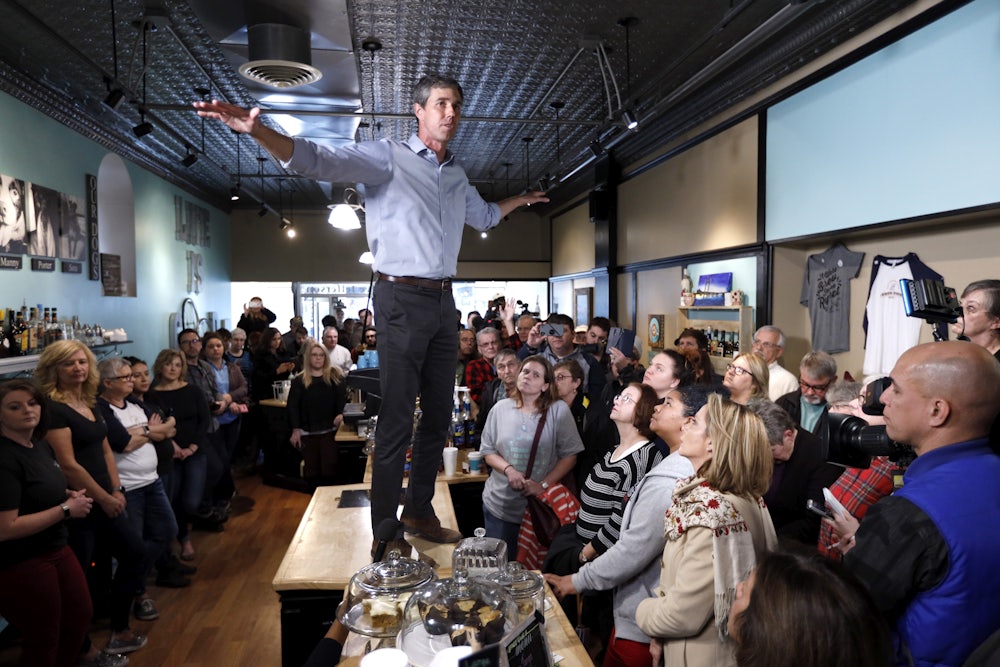

Finally, this week, O’Rourke announced he was entering the race. Even this was a multi-day affair, culminating in a swing through Iowa where he gave his spoken-word pitch while standing on coffeeshop countertops. The rollout of his decision also included a fawning profile in Vanity Fair, complete with photographs from Annie Leibowitz. “I honestly don’t know how much of it was me,” he told Joe Hagan, sounding a bit like a band member in Almost Famous. “But there is something abnormal, super-normal, or I don’t know what the hell to call it, that we both experience when we’re out on the campaign trail.” While other Democratic candidates have defined themselves by the policies they support, or their vision for the country, O’Rourke spoke about the nomination as if it was his birthright. “Man, I’m just born to be in it,” he said. “You can probably tell that I want to run. I do. I think I’d be good at it.” He had less to say about whether he’d be any good at running the country.

To be fair, some prominent people think he would be very good at it. People from Obama’s orbit, in particular, have singled O’Rourke out, giving credibility to the comparison. Though not a fan of his blogs, former Obama chief strategist David Axelrod has praised O’Rourke repeatedly, noting his vision “comes from a belief that, through politics, we can achieve a higher purpose.” Former Obama field organizer Lauren Pardi told NBC late last year that “Beto has a special ability—like President Obama did—to make people believe in the best version of America.” Obama himself made the comparison on Axelrod’s podcast late last-year, noting that voters see a similar authenticity in the two. “It felt as if he based his statements and his positions on what he believed,” he said.

But the similarities largely end on that most ineffable political quality of authenticity. Obama launched his political campaign in 2007 by arguing that the bipartisan vote for the Iraq War was a historic mistake, that universal health care was a moral necessity, and that our economic system was dangerously inequitable. O’Rourke lacks any platform whatsoever. He has no signature idea, and we know little about his political positions beyond the mushy centrism he exhibited in Congress. O’Rourke’s decision to spend the last five months blogging could be seen as an attempt to shore up another weakness: His lack of a particularly compelling biography. Spending one’s twenties as an aimless musician, as O’Rourke did, is hardly the stuff of Dreams of My Father.

Instead, the biggest thing that O’Rourke has in common with Obama, the 2008 candidate, is the belief that they can transcend a broken political system with lofty rhetoric about bringing people together. But when Obama spoke about healing divisions, millions of people believed him. And it still didn’t work. Obama came to his senses while in office, as the Republican Party committed itself to bigotry and intransigence, and he now spends his political capital and energy on reforming our broken democracy. Many of the Democratic candidates for president have their own proposals for doing so. O’Rourke just has a blog, and a big beautiful smile that some folks can’t resist. It’s as if the last ten years of American political life never happened.