Joe Biden has spent much of his invisible primary season—the time between when candidacies are declared and people actually go to the polls, the time when money given seems to matter more than votes cast—avoiding policy details. Avoiding, for that matter, much policy altogether. In its place, the Biden campaign appeared to make a bet that the former senator and vice president could win the Democratic presidential nomination on a combination of his “Uncle Joe” persona and a nostalgia for the bygone days of the Obama administration. But in a “change election” cycle, where one candidate has made having “a plan” a virtual campaign slogan, no presidential candidate, it seems, can avoid policy altogether. So, last Tuesday, Biden released his proposals for fighting climate change—one of the most pressing issues for the planet, and, importantly for the candidate, one of the most motivating issues for Democratic voters.

But Biden’s plan, people quickly realized, had one big problem: It wasn’t really his plan at all. Instead, it contained a number of passages lifted from the websites of various climate advocacy organizations. The incident recalled the plagiarism scandal that ultimately doomed Biden’s first presidential campaign in 1988, when he was found to have lifted portions of a speech from Neil Kinnock, who, at the time, was the leader of Great Britain’s Labour Party.

But was this year’s text appropriation a plagiarism scandal? Less than 24 hours after Biden was found to have used language from climate organizations, Politico was reporting that just about every Democratic presidential candidate—including senators Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris, and Cory Booker, and former Texas Representative Beto O’Rourke—was using language from other organizations on their campaign websites. Asked for comment, the Harris campaign offered the same explanation that Biden’s did. “These are statistics,” Harris spokesperson Ian Sams said.

This is, moreover, apparently common practice among campaigns. “While any journalist would be mad about getting plagiarized by another journalist, policy shops and advocacy groups are happy to have their stuff copied by a leading presidential candidate,” Vox’s Matt Yglesias wrote. In other words, it’s not a scandal, as Yglesias sees it, for campaigns to lean on experts when formulating policy. It’s sensible for nonexperts to lean on experts.

But this does point to another issue; potentially a problematic one. For all the policy work that Democratic candidates have put out, much of it is strikingly similar. With the first Democratic presidential debate fast approaching, it appears increasingly likely that candidates will spend their time on stage arguing about small differences in their emerging platforms. But this fixation on tiny policy details could overlook the two biggest issues facing Democrats: the need for a big, organizing message, and the need for a strategy to actually implement their policies. Without these, the websites full of proposals won’t be worth any more than the paper they’re not printed on.

It’s no surprise that Democrats have embraced progressive positions. The conventional wisdom following the 2016 election was that Sanders had lost the battle but won the war, and that the future of the Democratic Party was in his policy-heavy approach.

Medicare for All, Sanders’s most important 2016 idea, is embraced, in some form, by nearly every Democratic candidate. Yes, there are huge differences between Medicare for All—which would cover everyone and eliminate private insurance—and “Medicare for America,” the proposal supported by Beto O’Rourke, which would preserve employer-based, private coverage, insurance premiums, and deductibles. But embracing universal health care, in one way or another, is now pretty much the cost of entry for Democratic candidates.

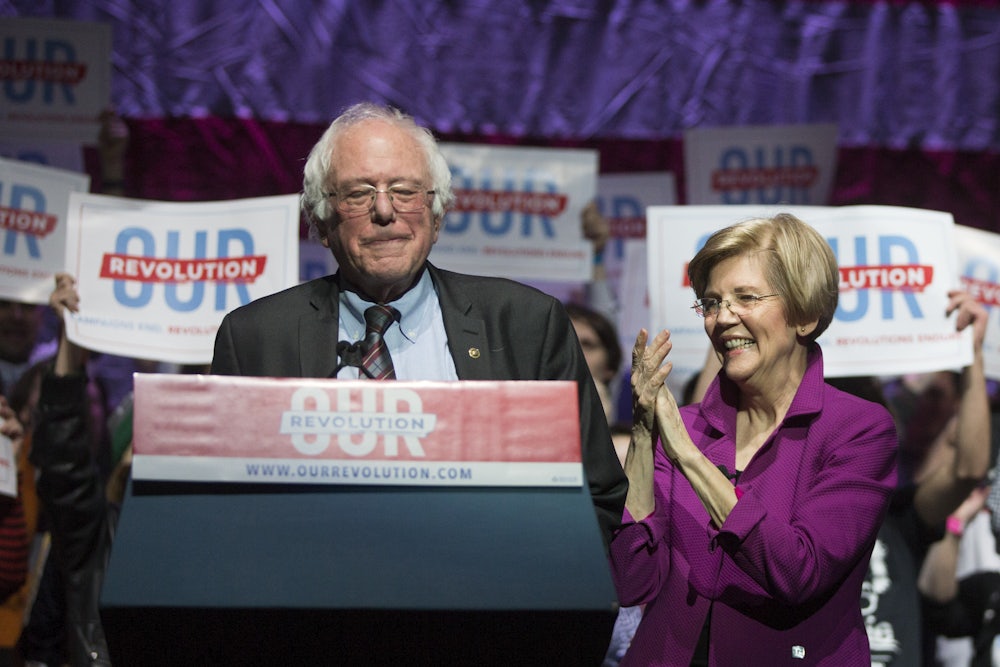

The idea overlap exists in a number of other areas, too. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, the policy pacesetters of the primary race, are leading the pack in guaranteeing access to higher education and on increasing taxes on the wealthiest individuals. Some candidates have underplayed climate change thus far, though that is starting to change. Beto O’Rourke and Biden both have released plans that represent what is, perhaps, the middle of the road of climate policy; both are relatively friendly to industry groups, though they both—particularly O’Rourke’s $5 trillion plan—would significantly change the American economy. Jay Inslee’s entire candidacy, meanwhile, is built around fighting climate change; most recently, he proposed stepping up international efforts to fight pollution and plans to phase out coal. Inslee came out against Biden’s plan last week, telling reporters, “I have to express disappointment that the vice president’s proposals really lack teeth, they lack the ambition that is necessary to defeat the climate crisis.” Sanders and Warren have also taken on the issue, with Warren’s campaign releasing a proposal based on the Marshall Plan last week.

Nevertheless, many leading contenders have embraced the Green New Deal, which, like Medicare for All, is a moniker that can be used for several different policy proposals. In broad strokes, Democratic candidates tend to support universal health care, large investments to fight the oncoming climate catastrophe, increasing taxes on the wealthy, and democratic reforms aimed at guaranteeing broad voter access.

That similarity across the field, however, could help Biden, who currently boasts a significant lead in most 2020 opinion polls. With a large group of candidates, all with broadly similar messages, struggling to break out of the single digits, Biden’s personality-driven, conservative approach appears to differentiate his brand. (Still, that conservative image took a hit last week when Biden’s long-standing embrace of the discriminatory, anti-abortion Hyde Amendment came back to bite him hard enough to cause an overnight conversion.)

At the same time, there is a sense in these early stages of the Democratic contest that candidates may be embracing policy wonkery at the expense of crafting a sharp political message. In Warren’s case, this doesn’t seem to be a handicap. Her approach, with a major policy released seemingly every other day, is pointillistic; her various plans—from breaking up big tech to re-energizing domestic manufacturing—are creating a cutting critique of the status quo. But for others, neglecting a strong, singular message suggests they may only be using policy planks to pay lip service to progressive goals.

And if they want to get into the weeds at this juncture, then, beyond just advocating for policy, candidates need a plan to implement it. It still seems unlikely that a Democratic president entering office in 2021 will have a majority in both the House and Senate, so there must be a way to put a bold agenda into practice. Warren again leads the way here—her plans often include a series of executive orders that she would sign. On the other hand, there is little reason to believe that Beto O’Rourke, who has argued that he will win over Republicans with his charming personality, can implement his sweeping voting rights plan.

But at the end of the day, in the run-up to this month’s first Democratic debates, candidates should care about differentiating themselves from each other as much as they care about differentiating themselves from Republicans and Trump—if for no other reason than political survival. But it matters beyond politics, too. If campaigns are ever to be more than mere horse races, with more than parimutuel punditry handicapping the personalities, then policy debates also need to be seized as educational opportunities. More than just crafting the most hashtag-worthy catchphrase, the best of the Democratic field will win a battle of ideas with, believe it or not, ideas.

Embracing those ideas, understanding them from the ground up, and bringing the electorate along for an inspiring, grassroots hayride should be what politics is all about. It is what’s needed to make a change election really change things.