Robert Mueller made a surprising assertion last month about the limits of his power. In his report on Russia’s interference in the 2016 election and President Trump’s potential obstruction of the investigation, the special counsel explained that Justice Department policy effectively prevented him from charging Trump with a crime while in office. But in his surprise press conference in May, he went even further. “[The report] explains that under long-standing department policy, a president cannot be charged with a federal crime while he is in office,” he said. “That is unconstitutional. Even if the charge is kept under seal and hidden from public view—that too is prohibited.”

This remains an open legal question, despite Mueller’s unequivocal assertion. The Constitution itself is silent on the matter, and no court has ever ruled otherwise because no sitting president has ever been indicted. Mueller’s nod to “long-standing department policy” likely was a reference to the so-called Dixon memo, a 1973 Office of Legal Counsel opinion in which Assistant Attorney General Robert Dixon concluded that there were multiple practical and constitutional hurdles that made it effectively impossible. “The spectacle of an indicted president still trying to serve as chief president boggles the imagination,” Dixon wrote.

That memo’s primary purpose, however, was not to conclusively decide whether a president could be indicted while in office. While it’s commonly assumed that the memo came about during the Watergate scandal, it instead sprang from the Justice Department’s efforts to prosecute Vice President Spiro Agnew in a tax-evasion case. Agnew argued that he was only subject to impeachment by Congress, and Attorney General Elliot Richardson asked Dixon to write an opinion on the question.

To understand the Dixon memo’s unusual origins and its continuing impact, I spoke with J. T. Smith, an attorney who worked as Richardson’s executive assistant during the Watergate scandal. Smith was present at the creation, so to speak, of the Justice Department’s policy on indicting a sitting president. He told me that if Richardson “had the benefit or detriment we have of the behavior of this particular White House, he almost certainly would say it’s high time this whole matter get revisited.”

Did you happen to see Mueller’s press conference the other day, where he said outright that it would be unconstitutional to indict a sitting president?

I saw that, and I’m not clear why he said it. It’s one thing to say that it is Justice Department policy, long standing, that a sitting president should not be subject to criminal process, but he sort of surprised me when he characterized it as being unconstitutional. Because the Dixon memo of 1973, I think, ends up on grounds that are policy-based more than Constitution-based, and indeed, the Dixon memo says that the Constitution doesn’t squarely address the topic.

Which is kind of interesting, because it has assumed over the last four years this sort of definitiveness to it. How did this memo come about?

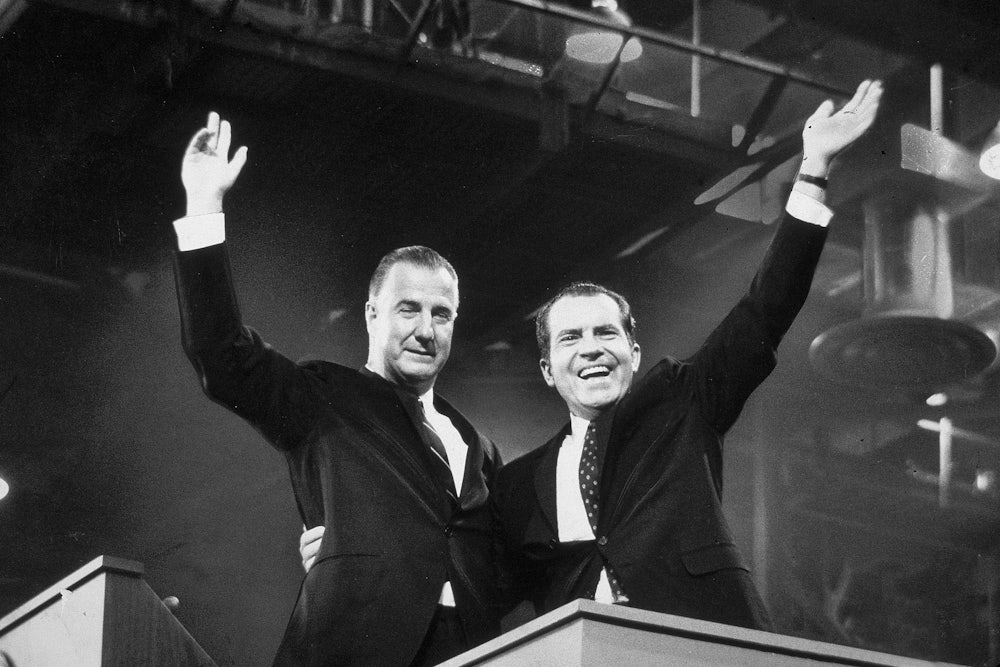

In the summer of 1973, Vice President Agnew was under serious criminal investigation by the United States attorney in Baltimore because of the deeds he had done as county executive and governor of Maryland and continued to receive cash payments while vice president of the United States. Learning about that, newly confirmed Attorney General Elliot Richardson basically decided that it is not tolerable to have a criminally tainted vice president a heartbeat away from Nixon, who is already embroiled in Watergate. And the practical question faced by the attorney general was how to engineer the vice president’s leaving the same office perfectly by resignation.

[Richardson] had to deal really with three parties: (1) the vice president and the vice president’s counsel; (2) the U.S. attorney and assistant U.S. attorneys in Baltimore; and (3) under the circumstances, the Nixon White House, including White House Counsel Fred Buzhardt and others. The situation was such that the vice president was capable of arguing, and did argue, that he should not be subject to criminal process, but only to impeachment. The prosecutors in Baltimore, like good prosecutors anywhere, felt that with Agnew’s poor character and with the record before them of his potentially criminal acts, he ought to be put in jail, like current circumstances where Pelosi, for better or for worse, says Trump ought to go to jail.

And then the White House had issues either way. They thought a criminal prosecution of the vice president would be a potentially adverse outcome, raising the inference that Nixon was subject to criminal prosecution. Conversely, they were worried that if an impeachment proceeding were to begin on the Hill with respect to the vice president, it would add opportunity and impetus for those in the House who were already suggesting that [for Nixon] in light of Watergate.

So, that was the lay of the land. The assistant attorney general in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel was really not in the loop to see the whole matter of Agnew being under criminal investigation. It was a deep secret known only to the U.S. attorney in Baltimore, Richardson, myself, and one or two other aides. But Robert Dixon, the assistant attorney general, had no idea until it broke in the newspaper in August. He would not have had any idea that this was going on.

And then the memo is published on September 24.

Yeah. And as you can see, it’s not something that was written in 24 or 48 hours. It’s a fairly significant piece of scholarship. I have no documented basis to say when, but it wouldn’t have been initiated any earlier than sometime in August 1973. I’d say no more than a month before it was final. And it was in a context where Agnew’s lawyers, I think, had filed a motion for determination by Judge Hoffman [arguing that] Agnew couldn’t be criminally indicted and was subject only to the impeachment process.

That led to the need for the Justice Department to file a brief in opposition, which has been referred to as the Bork brief, because Richardson, rather than leaving that to the Civil Division or the workaday portion of the Justice Department, turned to the solicitor general [Robert Bork] to take the lead on the briefs. So in parallel with that, Richardson, being a diligent lawyer and a believer in normal process, asked for an opinion of the Office of Legal Counsel as to this topic. And what you have in front of you is the result of Richardson seeking that opinion.

Now all of that is by way of context and background. The only thing that doesn’t appear directly on some kind of public record is that Dixon and his staff found the whole question—and by that, the question of whether the president was subject to criminal process and, more directly, whether a vice president was subject to criminal process—to be [such] a sufficiently difficult question, and one of first impression, that he called me in my capacity as the attorney general’s executive assistant at home one evening after normal hours, and wanted kind of offline advice as to how the attorney general hoped the opinion would turn out.

What did you tell him?

I remember telling him that he certainly hopes that it would find the vice president to be subject to criminal process. I don’t recall saying, “and he wanted it to say that a president wasn’t.” But anybody of more than average intelligence at the time kind of knew that that was the best way for it to turn out, because an opinion that said both the president and the vice president were not constitutionally immune to criminal process would have, in likelihood, led to an intervention by Nixon, White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, and Buzhardt to prevent the prosecution of Agnew.

So conceptually, there were three ways for the memo to turn out: neither subject to criminal process; both subject to criminal process; or vice president subject to criminal process, president not. And that was the only outcome that was, for lack of a better word, sustainable in the context how it had arisen. I say some of that in retrospect because at the time, as a 29-year-old staffer, what I knew that the attorney general hoped the opinion would say was that Agnew was subject to criminal process.

How much communication was there between Richardson and the White House during this period about the Agnew prosecution, these issues sort of swirling around? Was there sort of an ongoing dialogue?

Constant. Constant. But not so much between Richardson and the president, but between Richardson, Haig, and Buzhardt. I mean, it is nice to think of a world in which the Justice Department is pristine, and the White House should keep hands off, and anything Trump did to try to get his attorney general involved in Mueller, and all that. What Trump tried to do with [Don] McGahn and [James] Comey and others is grotesque, as is most of how Trump proceeds, because he doesn’t follow any form of normal etiquette. But, it’s my experience that there is close communication in normal times between an attorney general [and a president]. Take Bobby Kennedy, for instance, and his brother. The Saturday Night Massacre sort of dramatized the need for a measure of independence on the part of the attorney general, but before the Saturday Night Massacre, Richardson, on something like what to do about a criminal vice president, was of course in constant communication.

What was your impression of Richardson after working closely with him?

I became a close friend of his and I worked for him before the Justice Department [at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare], in the Department of Defense, and afterwards I was his general counsel when he was secretary of commerce. Then I worked for him in the State Department on law of the sea negotiations. So, my impression of him is that I’m not sure I can give you an objective impression. He was a friend and a mentor and one of the most wonderful human beings I’ve ever known. But it’s simplistic that he was some kind of saint who stood up to the White House and it was a no-brainer. In point of fact, he really had to wrestle with the circumstances because Nixon had appointed him to all these cabinet posts. He was a loyal Republican. So he had the moral fiber and the intelligence to do the right thing, but it wasn’t as simple as history may suggest.

So once this memo was made available, it seems like events moved pretty quickly. It came out in late September and Agnew was indicted in October. This seems like the kind of nail in the coffin for him.

I think the memo was being prepared in parallel with the so-called Bork brief, which made the same argument. But it’s a matter of historical fact that the original Office of Legal Counsel memo saying that a sitting president isn’t subject to criminal process wasn’t prepared with that being its primary purpose. Its purpose was to say that a sitting vice president was subject to criminal process, and then the analysis was prepared by way of a distinction between the two offices.

Why do you think that it’s assumed this decisive role in this question?

Well, it remained a fairly obscure matter until the Clinton impeachment. Ken Starr’s office prepared some kind of opinion that a president could be subject to criminal process, whereupon the Clinton Office of Legal Counsel in 2000 revisited the Dixon memo and took account of intervening Supreme Court decisions, including Clinton v. Jones. The Supreme Court unanimously said that a sitting president was subject to the civil process, which set the context for Clinton’s perjury that then became the central count of his impeachment. And it seemed to me that one ought to really seriously revisit the Dixon memo in light of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Paula Jones case. But obviously, the Clinton Justice Department chose to wrestle with the issue and come up with a reaffirmation of the Dixon memo. And so the Dixon memo doesn’t sit in isolation. You have to read it along with the 2000 memo, but that kind of resurrected and sprinkled holy water on the Dixon memo.

Elizabeth Warren recently came out with a plan for prosecuting a president. She said that she would appoint an assistant attorney general for the Office of Legal Counsel who would revisit that memo and revise it to make it possible to prosecute the president. Do you think that that’s the right step? Is there something else that should be done instead?

I think the right step should be that the policies established as Justice Department policies by the Dixon memo and the Clinton-era memo ought to be revisited. Is it good process to appoint a Supreme Court justice and ask him or her in advance how they’d rule on particular, vexed topics which heretofore have been avoided, even on Roe v. Wade? You get people, the more recent Republican appointees, saying they’re strong believers in stare decisis but they’re not called to say, “and I would overrule Roe v. Wade.” So appointing an assistant attorney general to be chief policy lawyer for the executive branch with an advance pledge on his or her part that they would reverse the Dixon opinion seems to me to be a little bit, I don’t know, a little bit askew.

But having said that, well, how would you get this policy changed? Could a differently composed Congress pass legislation somehow affirming that a president is subject to criminal process? I don’t know that that’s within the constitutional right of Congress. You have the problem obviously that the president is the chief magistrate. The whole prosecutorial function is vested by the Constitution in the executive branch. One of the conceptual problems that Dixon wrestles, short of declaring it unconstitutional to indict a president, is that technically anything an attorney general, U.S. attorney, or any prosecuting authority does is under the authority of the president. So can or would a president authorize his own indictment?

Which is kind of a strange thing, when you think about it.

Yeah, it’s very strange. But you have the logic that no person is above the law. And if a president were to, I don’t know, knife a subordinate in the Oval Office, killing that person, would you say, well, he can be indicted for murder three years hence when he’s no longer in office, or do something before that? Is murder an impeachable offense? You get riddles which you have to deal with.

If you think that Dixon and Richardson knew how this would evolve, and where we ended up today with this legal opinion, do you think they would have done anything differently at the time?

Well, I can say that I don’t think Richardson had any direct way in framing the Dixon opinion. He just asked Dixon to write an opinion, but the reason he asked him to write the opinion was because he was very earnestly in pursuit of getting Agnew out of a heartbeat away [from the presidency]. That was the sum and substance of it.

Whether Richardson even focused at the time on the extent to which Dixon, in distinction to a vice president, said that a president was untouchable by criminal process, I don’t know. Richardson probably certainly realized that that was comforting to the White House in a context where Richardson actually needed the White House’s green light to proceed with the prosecution.

If you’re asking me, would Richardson, if he were alive and with hindsight, say that was the right outcome for all times—to say that a sitting president regardless of circumstances should not be subject to criminal process—I don’t think he would agree with that. And if he had the benefit or detriment we have of the behavior of this particular White House, he almost certainly would say it’s high time this whole matter get revisited.

This conservation has been edited for length and clarity.