Last summer, students at the University of Manchester arrived in their newly refurbished Students’ Union building to find some words of advice painted on a wall before them:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too,

If you can wait […]If you can dream […]

If you can think […]

If you can talk […]

Then the poem exclaims, “Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it, / And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!”

“If–” by Rudyard Kipling was recently voted “the most beloved poem in Great Britain” and has long been a staple of graduation speeches and motivational posters. But the Manchester students balked. It was “deeply inappropriate,” they felt, for a twenty-first–century multiethnic student community to be lectured at by the “author of the racist poem ‘The White Man’s Burden,’ and a plethora of other work that sought to legitimate the British empir[e] … and dehumanise people of colour.” In a brilliant, Banksy-like maneuver, the students painted over Kipling’s verses with Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise.”

If a writer harbored bias, shall we never speak his name? Or when he wrote with insight, might we read him all the same? Christopher Benfey opens his book about Rudyard Kipling with the inevitable questions. He answers by coming neither to praise Kipling nor to bury him, but to explore him as more than the author of some now-notorious couplets. A boundlessly prolific spinner of verse, stories, and novels for adults and children alike, Kipling managed to be “the most popular and financially successful writer” of his era, as well as one of the most acclaimed—becoming the first English-language author to win the Nobel Prize, at just 41. And though he may by now have become the “most politically incorrect writer in the canon,” he impressed many postcolonial writers, too. Born in Bombay in 1865 and beginning his career as a journalist in Lahore and Allahabad, Kipling knew India more intimately than any other British writer, giving his work, says Salman Rushdie, an “undeniable authority.” Michael Ondaatje weaves Kipling’s novel Kim into The English Patient, likening Kipling’s pages to “a drug of wonders.” Maya Angelou herself said that she “enjoyed and respected Kipling.”

Most of all, Benfey argues, in the animating insight of this book, Kipling was more than a bard of the British Empire. In a decade-long period of traveling and living in the United States, Kipling strove to be “a specifically American writer”—to tap into the energy of this continental power, to endow it with a literature befitting its greatness, and even, perhaps, “to write the Great American Novel.” If—the first sustained account of Kipling’s American years—argues that, to a very large extent, he succeeded.

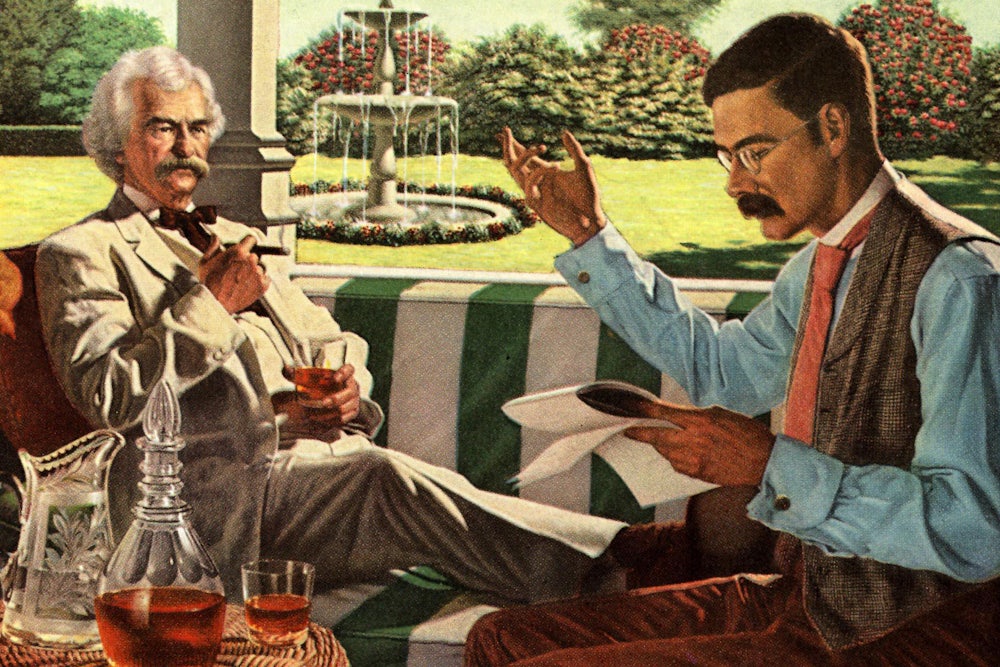

“East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,” Kipling famously wrote. But it was in order to meet Twain—Mark Twain—that Kipling said he made his first trip to the United States, from India, at the age of 23 in 1889. He sailed across the Pacific, which meant he met America’s West first, in the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown, the salmon canneries of the Columbia River, Yellowstone geysers, and Chicago slaughterhouses.* Three thousand miles later, he turned up unannounced on his idol’s doorstep in Elmira, New York. They talked for two hours, Kipling awestruck in the presence of “the oracle”—and Twain impressed by this polymathic young man from India, as outlandish, one of Twain’s daughters remembered, as “a denizen of the moon.”

Kipling had fallen in love with the United States through its literature, from Twain to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose galloping meter and narrative flow would heavily influence Kipling’s own ballads. On his 1889 trip, he fell briefly for an American woman, too, a friend’s sister studying at Wellesley. Arriving in London that autumn, Kipling became fast friends with an American writer and literary agent named Wolcott Balestier, whose sister Carrie he grew close to in turn. Kipling and Balestier teamed up to write an adventure novel, set in Colorado and Rajasthan, that put their cross-continental expertise to the page. Balestier wouldn’t live to see The Naulahka: A Story of East and West published; he died of typhoid in December 1891, just shy of his 30th birthday. Six weeks later, Kipling married Carrie Balestier in a small ceremony in London—Henry James gave away the bride—and the pair sailed for the United States on the first leg of their honeymoon.

Outside Brattleboro, Vermont, the newlyweds bought a parcel of land with a view of Mount Monadnock—a vision, Kipling wrote, of “everything that was helpful, healing, and full of quiet.” They commemorated their purchase by building a snowman on the plot in the shape of the Buddha. In due course followed a baby, Josephine, born in Vermont at the end of 1892. Then came a house, largely designed by Kipling himself. Ninety feet long but just one room wide, a confection of warm, polished hardwood, the home resembled “a houseboat perched on the hillside like Noah’s Ark on Ararat.” They named it Naulakha.

It was at Naulakha that Kipling conjured many of the prose works he’s best known for today. He started to sketch out the novel that became Kim in Vermont, and wrote what he called a “genuine out and out American story,” Captains Courageous, set amid a Gloucester fishing fleet. For Josephine, he began to write a series of animal stories that would later be collected into the volume Just So Stories. The title appears to describe why different animals turned out “just so”—“How the Camel Got His Hump,” “How the Elephant Got His Trunk”—but actually had a more intimate source: Every time Kipling told the stories to his daughter, “Josephine insisted that each story be told exactly the same way—hence, ‘just so.’” Kipling also wrote The Jungle Book at Naulakha, the story of an Indian boy, Mowgli, raised by a family of benevolent wolves. For all that the book taps into Kipling’s experience of India, it also captured something of his sentiments about America as a wild, if nurturing, place. Kipling was convinced, Benfey observes, that “violence was at the molten core of American life,” and that in Vermont (yes, Vermont) “he was living in a lawless jungle.”

The Brattleboro idyll didn’t last for long. Early in 1895, the Kiplings spent six weeks in Washington, D.C., where they befriended a number of prominent political figures, including the rising Republican star Theodore Roosevelt, whom Kipling “liked … from the first.” But later that year, Kipling was incensed by a diplomatic struggle over the border between British Guiana and the American-backed Venezuela, which his new friends threatened to blow into war. Closer to home, he got into a public fight in 1896 with Carrie’s alcoholic brother Beatty, which spilled embarrassingly into the courts. The brouhaha ruined Kipling’s sense of peace. On the eve of a court hearing on the matter, Kipling suddenly decided to pack up and leave for England. “It is hard to go from where one has raised one’s kids and builded a wall and digged a well and planted a tree,” he wrote; “the hardest thing I had ever had to do.”

It would be three years before the family returned to the United States for another go. On the voyage out, the Kipling children—his second daughter, Elsie, was born in 1896, followed by a son, John, the next year—caught bad colds, and soon both Rudyard and Josephine were seriously ill with pneumonia. Kipling turned the corner, as Josephine got suddenly worse. She died in New York, aged six. Kipling could scarcely express his grief. “My little Maid loved [America] dearly (she was almost entirely American in her ways of thinking and looking at things),” he wrote, months later. “I don’t think it likely that I shall ever come back to America.” And he never did.

If delivers a terrific reminder of (or introduction to, as the case may be) Kipling’s exuberant literary gifts. “I believed that he knew more than any person I had met before,” Twain enthused; while Henry James marveled at “his precocity and various endowments.” Few English authors have ever managed to be as accomplished in poetry as in prose. T.S. Eliot, introducing a posthumous collection of Kipling’s verse, suggested that Kipling be judged “not separately as a poet and as a writer of prose fiction”—the way Thomas Hardy might be—“but as the inventor of a mixed form.”

His writing conveys an extraordinary ear for accent, rhythm, and idiolect. Benfey notes one tiny but telling example: In his poem “Buddha of Kamakura,” Kipling placed the stress correctly on the second syllable of “Kamakura” rather than the third, as most English-speakers would. The orality of Kipling’s writing must be one reason why his children’s literature endures particularly well: He knew how to write to be read aloud. Paradoxically, Kipling’s skill at capturing specific voices may also account for why some of his work doesn’t resonate so well a hundred years later, as speech habits change faster than written ones. (Particularly jarring is his use of “thee” and “thou” to capture his Hindustani-speaking Indian characters’ use of familiar personal pronouns.)

If the ballad was the genre in which Kipling triumphantly manipulated poetic voice, the short story was where he discovered the widest room for maneuver in prose. Though best remembered for animal stories, Kipling also flirted extensively in his fiction (and sometimes personal practice) with spiritualism and the paranormal. “The Finest Story in the World” introduces a character who channels stories from his past lives, which the narrator frantically transcribes in hopes of proving that reincarnation is true. In “An Error in the Fourth Dimension,” Kipling opens up the possibility of another realm accessed through drugs and hallucinations, informed by his own occasional use of opium. Kipling’s exploration of these mystical frontiers—between life and afterlife, physical and psychic—offers an intriguing counterpart to his better-known preoccupations with the boundaries between East and West, wilderness and civilization.

Benfey strolls through Kipling’s American years with the sensibility of a flaneur, pausing here over particular points of interest, turning back there for another look. The approach delivers memorable insights. He convincingly reads Kim as an Indian Huckleberry Finn, noting that both books feature boyish heroes who navigate a “river of life” (Kim’s Grand Trunk Road standing in for Huck’s Mississippi) “in shape-changing disguises, ‘passing’ … for what they are not.” Benfey also teases out the motif of Noah’s Ark in Kipling’s work, from its appearance as a device in his fiction, to the arklike design of Naulakha, to a cipher with which he signed his drawings, of an ark nested inside a capital letter “A”: “Ark + A, to be pronounced ‘RK.’” (Kipling elegantly illustrated Just So Stories himself, showcasing a family talent: His father, Lockwood, was an accomplished artist and educator at art schools in Bombay and Lahore; two aunts married celebrated painters.)

A discussion of Kipling’s friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, which was forged over visits to the Washington Zoo, contrasts Roosevelt’s admiration for the grizzly bear with Kipling’s for the North American beaver. “One might discern in the two friends’ diverging views two contrasting notions of empire,” Benfey observes: Kipling’s of an unassuming British Empire hard at work building things; Roosevelt’s of a charismatic, roaring American astride its turf.

But too often Benfey lets go of the bright ideas that bob through If like a fistful of balloons and allows them to float away. Benfey is quite right that Kipling “offers little of the pat solutions, the ringing advice that he is often reputed to supply”; indeed, “If–” itself ends with terrible anticlimax, when all the air energetically pumped into the earlier verses leaks out in the flatulent final phrase “you’ll be a Man, my son!” If concludes with an unsatisfying epilogue on citations of Kipling during the Vietnam War, which feels both too little (in terms of what it says about Kipling) and too late (leaping straight from the 1910s into the 1970s).

“A tantalizing sense of ‘what if’ hangs over Kipling’s American years,” Benfey writes. What if … what? He appears to mean what if Kipling had spent the rest of his life in the United States—but If doesn’t go far enough toward an answer. At least one biographical consequence might have followed: Had Kipling remained in the United States, his son, John, would not have gone off to fight in the trenches in 1915 (before the United States entered the war) and would not have been killed in his first battle. John’s death devastated Kipling, and his own health markedly declined. After the incredible output of the 1890s and early 1900s, the most significant works of Kipling’s later years (he died in 1936) were the epitaphs he wrote for the Imperial War Graves Commission.

As it was, after moving away from the United States, the Kipling family began wintering in South Africa, where Kipling became close friends with men who championed an aggressive British expansionism, Alfred Milner and Cecil Rhodes. (Kipling later said that “If–” was based on the character of Leander Starr Jameson, a henchman of Rhodes.) He developed “strident, and increasingly repellent” political views, becoming a staunch Conservative and champion of white imperial federation, and an equally fervent enemy of Irish and Indian nationalism. He became, in the marvelously succinct judgment of George Orwell, “a jingo imperialist … morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting.”

What If makes clear, however, is that Kipling’s offensive politics must be understood as a product of American influence as much as British. Kipling knew Roosevelt before he knew Rhodes, and he recognized that what he could bring to his American friends was “an appropriate language for imperial ambition.” That’s why his notorious call to “take up the White Man’s Burden” was addressed to the United States on the conquest of the Philippines. An anxiety, in turn, about what surging American ambition might mean for the British Empire comes through in the doomsdayish evocations of “Recessional”: “Far-called our navies melt away; / On dune and headland sinks the fire: / Lo, all our pomp of yesterday / Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!”

So where does If leave us with respect to the question of how to read Kipling today? As media coverage of the University of Manchester episode showed, serious discussions about the legacies of empire can devolve into caricatured battles between “racists” and “snowflakes.” Anchoring Kipling in American history and literature shows how much more extensive and complicated the legacies of empire actually are. Maybe the Manchester students left “If–” just where it should be: blurred but still visible behind Angelou’s verses, a shadow in the whitewash.

* A previous version of this piece incorrectly referred to “Yosemite geysers.”