There was an intriguing recurring theme in Bill Taylor’s testimony for the impeachment inquiry earlier this week. The top U.S. diplomat in Ukraine laid out in his 15-page opening statement how President Donald Trump and his allies manipulated U.S. foreign policy to undermine his domestic political opponents. Time and time again, Taylor describes how Trump’s allies weren’t satisfied that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy privately agreed to pursue investigations that would legitimize Trump’s attacks on Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton. Zelenskiy had to announce it publicly.

Taylor described a series of conversations in which Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, laid out Trump’s intentions to him. Zelenskiy had previously signaled that Ukrainian officials would look into Burisma, the company where Biden’s son once held a board seat, as well as a conspiracy theory involving a mythical DNC server. Sondland, Taylor testified, “said that President Trump wanted President Zelenskyy ‘in a public box’ by making a public statement about ordering such investigations.”

According to Taylor, Sondland told him that he’d spoken with Zelenskiy about the need to “clear things up” to avoid a “stalemate,” which Taylor took to mean Trump’s freeze on military aid, and that Zelenskiy had agreed to do a CNN interview. After the freeze was lifted in mid-September, Taylor said he feared that Zelenskiy “would make a statement regarding ‘investigations’ that would have played into domestic U.S. politics.” That, of course, was Trump’s likely goal: to have a foreign head of state, apparently acting of his own volition, validate his smears against domestic political rivals on American television.

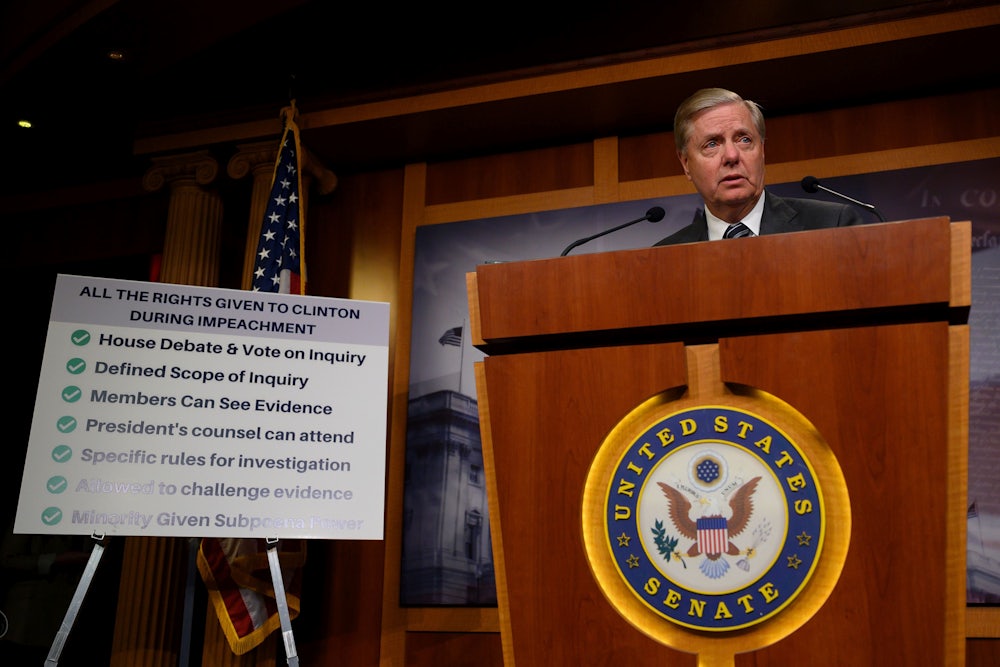

Trumpworld appears to be using the same playbook against Republican senators by pushing them into a public box. South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham introduced a resolution on Thursday that criticized the House’s impeachment inquiry on procedural grounds. More than three dozen GOP senators are listed as co-sponsors, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. Graham, in his role as the Senate Judiciary Committee chairman, also released a memo that described the House proceedings as “unprecedented and undemocratic.”

Many of the concerns outlined by Graham are superficial. Holding the hearings behind closed doors in a SCIF—a secure room designed for discussing classified information—makes sense when questioning diplomats about national-security matters. (It also makes it harder for witnesses to coordinate their testimony.) House Republicans aren’t being denied access to the sessions. So long as they sit on the relevant committees, they can and have participated in the inquiry. Nor is any of this novel. Andrew Napolitano, a Fox News legal analyst, noted on Thursday that Democrats were operating under rules established by former Speaker John Boehner in 2015. Under those same rules, House Republicans held multiple closed-door hearings to depose witnesses during the congressional Benghazi investigations.

More broadly, the resolution and the memo adopt some of the White House’s talking points about the inquiry’s legitimacy, albeit tepidly. They note that the House didn’t vote to formally open an impeachment inquiry after Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s announcement last month, as it had in the Nixon and Clinton impeachment sagas. That would give House Republicans the ability to subpoena witnesses of their own. The resolution also criticizes House investigators for denying Trump certain privileges enjoyed by Bill Clinton’s legal team in 1998, including the ability to sit in on all depositions and question the witnesses themselves. House Democrats are reportedly planning public hearings next month that would ameliorate most of these concerns. Trump will have ample opportunities to defend himself during the Senate trial as well.

The resolution’s concerns about the integrity of the impeachment process can’t be separated from Trump’s efforts to subvert that process. The Senate effectively becomes a court when it conducts an impeachment trial. A group of House lawmakers will serve as prosecutors; Trump’s lawyers will act as defense attorneys. Chief Justice John Roberts will preside over it. And the senators themselves are the jurors. They will hear the evidence and testimony, deliberate amongst themselves, and then vote on whether the president is guilty or not guilty. Every senator knows the gravity of the situation. It will likely be the most important vote that many of them ever cast.

Trump’s allies aren’t taking any chances. Just as they tried to box in Zelenskiy, so too are they now trying to box in Republican senators. Earlier this week, The Daily Beast reported that Trump recently fumed to his allies that the GOP’s Senate majority hasn’t defended him as enthusiastically as he wants. Most of that frustration, the report said, was directed at Graham and McConnell, who introduced Thursday’s resolution. Trump wants his future jurors to pass judgment on the inquiry—and his own actions, by extension—before the House can finish or formally present their evidence.

In practical terms, this is an oblique form of jury tampering. Those who vote in favor of the resolution will find it much harder to justify a vote to convict Trump later in the process. Those who vote against it, on the other hand, can expect the same treatment that Trump gave Utah Senator Mitt Romney earlier this month. After Romney criticized Trump for openly asking China to investigate Biden, Trump angrily denounced him on Twitter as a “pompous ass.” The Club for Growth also launched a $40,000 ad campaign in Utah that labeled Romney as a “Democrat secret asset.” Forty grand and a handful of Trump tweets aren’t likely to do any real damage to Romney’s electoral hopes—he isn’t up for re-election for another five years. But it’s an unmistakable warning shot, directed against any other Senate Republicans who might openly air their concerns about the president’s misconduct.

All of this tells us three things about the inquiry’s effect so far. First, Trump and his allies know they’re losing badly. The president is accustomed to shaping the news cycle and the narrative through tweets and executive orders. The impeachment inquiry wrenches that power away from him and places it firmly in the Democrats’ hands. This problem runs deeper than mere optics. As I explained this week, the available evidence is so damning that the White House can’t really present an honest defense of his actions. Trump’s best hope for survival is to delegitimize the process itself so Republican senators can’t justify a vote that reifies it.

Second, it’s not guaranteed that the Senate will acquit Trump. There are no signs of open defections yet from within the GOP caucus; even Romney told The Atlantic this week that he’s “strenuously trying to avoid making any judgment.” But most senators aren’t rushing to the president’s defense, either, and the White House knows it. “The picture coming out of it, based on the reporting that we’ve seen, I would say is not a good one,” South Dakota Senator John Thune, the second-highest ranking Republican in the Senate, told CNN after Taylor’s testimony. “Indeed, some Republicans are growing increasingly uneasy about the inquiry,” The New York Times reported on Wednesday, “and fretting that it could get much, much worse for them.”

Finally, Trumpworld’s latest counter-attack against the impeachment inquiry bolsters the allegations that animate it. Taylor’s testimony describes a campaign by Trump and his allies to coerce an erstwhile ally into laundering his political talking points through legitimate institutions. The vehicle was the Ukrainian government then; now it’s the United States Senate. The leverage was $391 million in military aid then; now it’s Trump’s ironclad grip on the Republican primary electorate. The target was Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy then; now it’s 53 GOP senators.

Naturally, the president is free to grant or withhold his political support to anyone he chooses. The same can’t be said for congressionally-allocated military aid. If this is how Trump and his allies coerce members of their own party, it’s not hard to imagine that they would do the same to Ukraine.