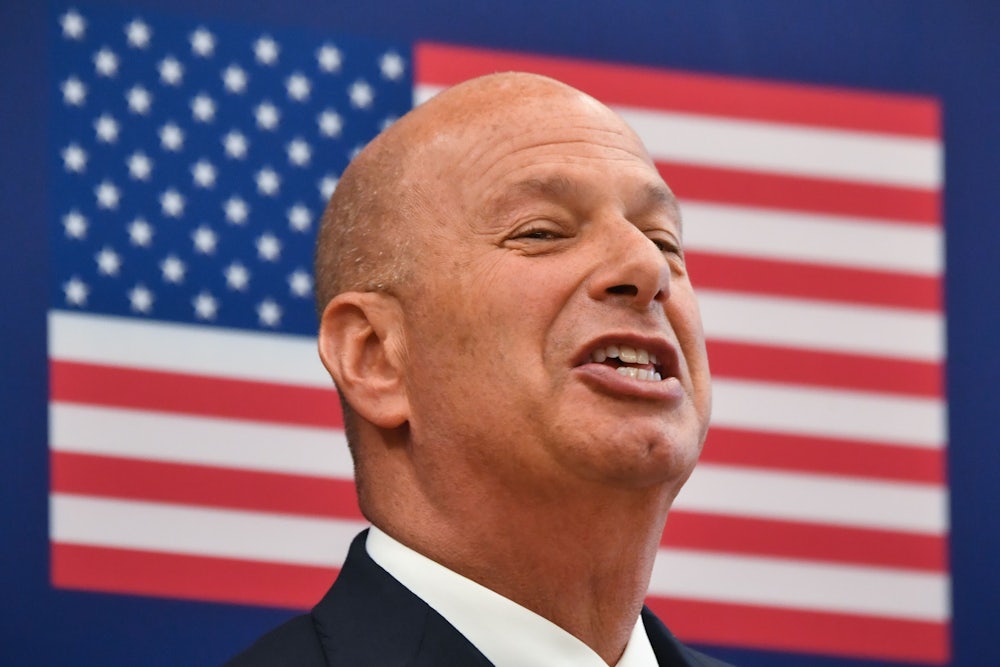

Those who’ve followed the Ukraine scandal are familiar by now with Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union. He’s a key player in the alleged scheme to subvert President Donald Trump’s political opponents by coercing Ukraine into launching sham investigations. Unlike many of the other figures in the scandal, Sondland is not a real diplomat. He got a plum ambassadorship in Europe the old-fashioned way: by donating more than $1 million to the president’s campaign and inaugural committee.

This is not some great secret. A relatively brief biography from The Washington Post, published earlier this month, found more space to discuss his history of funding various GOP candidates than Sondland’s own business dealings. When he testified before Congress a few weeks later, The New York Times described Sondland, who is an Oregon hotelier by trade, as “a Trump campaign donor” on second reference, as if that were his actual profession. The Wall Street Journal unsparingly summarized him as “a Republican donor and former hotel executive with no diplomatic experience before his Brussels posting.”

Some of Trump’s corruption is without precedent in modern American history. But rewarding high-dollar financial backers with diplomatic posts around the world is an all-too-familiar bipartisan tradition in Washington. Barack Obama nominated dozens of top Democratic donors to represent the United States in foreign capitals, as did George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton before him. This is an unseemly practice even in the best of circumstances. And while ending it should not be the biggest takeaway from the Ukraine scandal, it should still be one of them, because it is an embarrassment to the country.

In fairness to Sondland, his path to his ambassadorship isn’t an unusual one in the Trump administration. In April 2017, NBC News reported that Trump had already nominated at least 14 ambassadors who had donated to his inaugural committee. The average donation was around $350,000, a figure that’s slightly skewed by some of the biggest contributors. Jamie McCourt, the former Los Angeles Dodgers owner who now serves as the U.S. ambassador to France, donated roughly $50,000. Kelly Knight Craft, who served first in Canada and then at the United Nations, donated $1 million alongside her husband. Sondland contributed the same amount.

Not all of Trump’s non-career ambassadors gave him money. Some of the most important posts have gone to other elected officials. Jon Huntsman and Terry Branstad, who respectively serve as ambassadors to Russia and China, previously served as governors. So did Nikki Haley, who represented the U.S. at the United Nations until earlier this year. Scott Brown, the current ambassador to New Zealand, is a former Massachusetts senator. But even key diplomatic posts aren’t off-limits to those who’ve made financial contributions: David Friedman, who donated $50,000 to the Trump campaign and the RNC in 2016, currently serves as U.S. ambassador to Israel.

Telecommunications advancements and the modern campaign-finance system helped transform top diplomatic posts into lucrative sources of patronage. The White House taping system recorded Richard Nixon discussing the process in candid detail. “My point is that anybody who wants to be an ambassador must at least give $250,000,” he instructed White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman in 1971. “Yeah,” Haldeman replied, “I think any contributor under $100,000 we shouldn’t consider for any kind of thing.” Nixon later suggested in the tapes that his personal lawyer had told donors that a quarter-million dollar contribution to his 1972 re-election campaign would be the minimum requirement for an ambassadorship.

Modern presidents probably aren’t so explicitly transactional about the practice. But there’s strong evidence that lush overseas postings flow frictionlessly to a presidential candidate’s most generous backers. In 2012, two Pennsylvania State University researchers published a study that found a strong correlation between non-career appointments, placement in safe countries, and the size of the nominee’s campaign contributions. Drawing upon data from Barack Obama’s first term, the researchers found that campaign donations between “$650,000 and $700,000 generate a 90% probability of appointment to a [wealthy developed country] for personal and bundled campaign contributors respectively.”

A quick glance at the list of U.S. ambassadors to the Court of St. James’s—the formal title for diplomats sent to the United Kingdom—underscores the situation. Woody Johnson, the current ambassador and an owner of the New York Jets, donated $1.5 million to Trump’s inaugural committee and campaign efforts. Johnson’s predecessor, Matthew Barzun, served as Obama’s national finance chairman and bundled more than $1 million for his campaign. Barzun’s predecessor, Louis Susman, reportedly earned the nickname “the Vacuum Cleaner” for his fundraising skills on behalf of Democratic politicians. Susman’s predecessor, Robert Tuttle, gave more than $100,000 to George W. Bush’s campaign. Tuttle turned out to be quite fortunate to have earned the post with such a scant offering: The PSU study estimated that the price range for London “lies between $650,000 and $2.3 million.”

While their personal connections to presidents may give donor-ambassadors an edge when it comes to policy decisions, they are hardly the most qualified people to take the job. That inexperience can bring scandal. Cynthia Strom, one of Obama’s ambassadors to Luxembourg, resigned the post in 2011 shortly before an inspector’s general report described her as “aggressive, bullying, hostile, and intimidating.” NPR reported that some State Department employees accepted transfers to Kabul and Baghdad as a result. Larry Lawrence, who raised millions for Democrats and later served as Bill Clinton’s ambassador to Switzerland in the 1990s, was fined by the FEC for exceeding federal donation limits. Lawrence’s body was later exhumed from Arlington National Cemetery after it emerged that he had fabricated his service in World War II.

Trump’s appointees are building upon that not-so-proud tradition. Sondland, for instance, allegedly helped Trump carry out his scheme to coerce the Ukrainian government while career foreign-service officers raised red flags. Others seem to lack the temperament or sensibility for sensitive diplomatic postings. The Times recently reported that David Cornstein, a jewelry-store owner who now serves as the U.S. ambassador to Hungary, is taking extraordinary steps to curry favor with Viktor Orban, the country’s illiberal prime minister. Cornstein reportedly argued Orban’s version of events when the Hungarian government forced out the U.S.-linked Central European University and took Budapest’s side when a Russian bank suspected of money laundering set up shop in the country, undermining U.S. foreign policy interests.

Trump’s ambassadors may have finally prompted Democratic candidates to rethink the bipartisan practice. In a foreign-policy plan she released in June, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren vowed to “end the corrupt practice of selling cushy diplomatic posts to wealthy donors” and urged other candidates to do the same. It’s uncertain whether the Ukraine scandal will be enough to convince the Senate to oust Trump from office. But Sondland’s role in it should be more than enough for senators to stop aiding and abetting these corrupt practices, and firmly rule out confirming any more donor-ambassadors in the future, whether they’re appointed by Trump or by any of his successors.