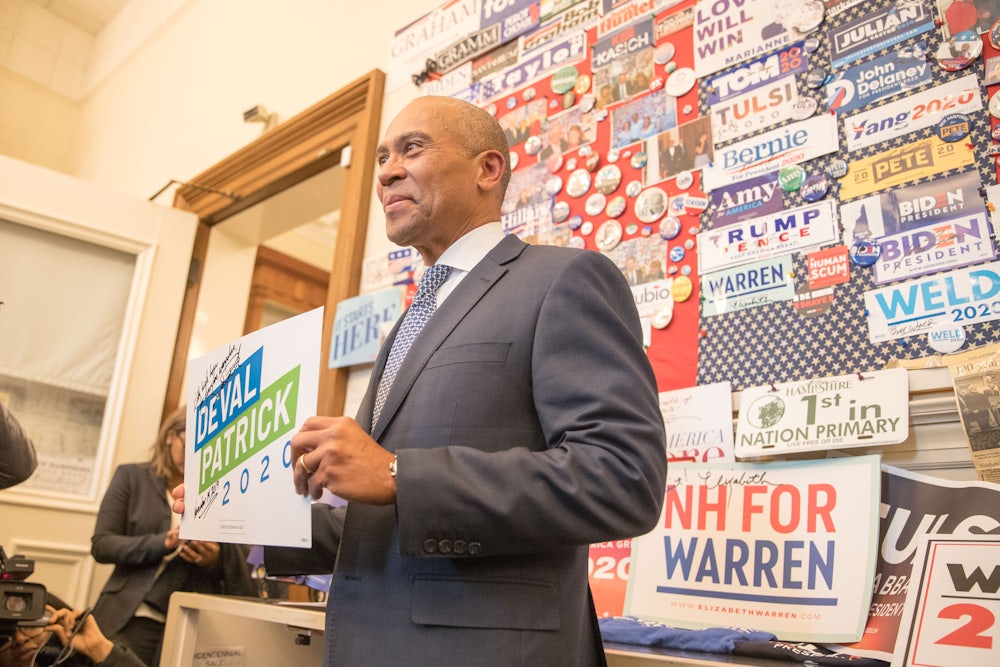

Just as the potential candidacies of billionaires Howard Schultz and Michael Bloomberg have left us to wonder about who might be the constituency for such a transparent defense of the ruling class, today’s entrance of former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick into the presidential race makes alarmingly little sense—at least from the perspective of “winning votes.” Who is clamoring for a presidential candidate from the bowels of Bain Capital? Who feels underserved by the current Democratic presidential field, packed cheek to jowl with wannabes who also support a public option over Medicare for All, who believe that extreme wealth is not inherently bad, and who promise to not alienate swing state voters by promising to improve their lives? What is happening?

There can be no single, satisfying explanation for Patrick’s baffling decision. It is undoubtable that ego plays a role; ‘twas ever thus: Anyone who believes that they would be a good president and enjoy doing it is pretty suspect, even if they’re right. Patrick’s candidacy, however, is unique in that it can be understood as the logical endpoint of a media culture which hews to the belief that what Wall Street guys have to say about the world is, by definition, endlessly fascinating—and which, consequently, treats these flagitious aristocrats as wise men of society who must be consulted, courted, and coddled by whoever wishes to be president.

Though Bloomberg might have the plushest coffers (and a truly abysmal record), Patrick is an equally horrible emissary from the gilded encampment of Wall Street. As the Huffington Post’s Zach Carter documented last year, Patrick made his millions from providing consultancy services to companies profiting from some of the most miserable activities in America’s thriving profiting-off-misery sector, most notably helping a GOP donor’s “notorious” subprime mortgages business, Ameriquest. Patrick made $360,000 a year at the company, which was responsible for 2,500 foreclosures in Detroit alone. In 1999, two years after the Department of Justice—where Patrick served as assistant attorney general in the civil rights division—signed a $176 million settlement with Texaco for racial discrimination against its employees, Patrick joined the company as its general counsel. (His primary duty at Texaco was to ensure the company grew into an even larger behemoth through a merger with Chevron.) In a primary where Joe Biden’s fundraiser with a fossil fuel executive was bad enough to cause a stir, what’s going to happen when a former Texaco executive jumps in?

While Patrick will surely argue that he pursued the same values in the corporate world as he did in politics, Carter reported that Patrick was “not so much a reformer as he was a public relations figure,” giving “corporations a story to tell about the good things they were supposedly doing—even if when they were simultaneously busying themselves with very bad things.” It makes sense that corporate America, under attack from the left, would send one of their most trusted turd-polishers to a Democratic primary process that seems to be slowly drifting away from them. As Joe Biden fails to deftly dominate the field as predicted, leaving Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren with decent shots at winning, Wall Street guys must surely be freaked out.

In fact, we know that they are freaked out, thanks to the comical lengths that the media has gone to ask various Wall Street guys about just how freaked out they are about the Democratic candidates. Financial sector factotums might be second only to working white class voters in diners in Trump Country in terms of how much attention the media feels it must pay to them, and how the media sees their opinions as a valuable lens into politics. Over and over, we must hear about their fretting, their jitters, their discomfort with the options ahead of them.

In October, Bloomberg quoted Wall Street analysts who described Warren as a threat to the stock market. (There was no mention of Sanders, who would be at least as threatening as Warren, anywhere; this is a common theme.) The Wall Street Journal, appropriately enough, journaled that Wall Street was “fretting” about Warren the same month. In September, CNBC reported that some of Wall Street’s top blokes would back Trump over Warren; one claimed a Warren presidency “would be like shutting down their industry.” In April, New York reported that Wall Street Democrats were “absolutely freaking out” about what they saw as the disappointing array of 2020 candidates. Politico did versions of that piece in October and January. The New York Times did one just a couple weeks ago. For a little twist, in June, several outlets wrote about how Wall Street disapproved of Bernie Sanders’s plan to pay off student loan debt, with Bloomberg reporting that the “potential for higher costs and lower volumes has the financial industry spooked.” Another twist: In July, Politico wrote about how Warren wouldn’t be as dangerous to Wall Street as Sanders, since she’s “been very clear that she believes in fair capitalism.” Finally, earlier this week, Politico reported that Deval Patrick’s candidacy was a direct response to donor anxiety— according to one anonymous friend of Patrick: “This is coming from Wall Street. They’re terrified of Warren.”

The message from on high is clear—Democrats must not do anything to hurt our bottom line—but the fact that there are so many willing vessels for this message in the media is telling. If you’re a Wall Street guy, you can call up a bored reporter and serve up a song-and-dance about how all your mates are really worried about this Warren lady, and rest easy knowing this message will be treated as important national news and not dismissed with the correct response, which is: Yeah, duh? If you are an analyst at Citi, for example, a news outlet might write up your note to clients that lots of rich people are worried about Warren (but don’t worry, because moderate Democrats are still on board to tank her priorities). Because you are an Analyst. At Citi. (And you only have that job today because American taxpayers forked over $476.2 billion in cash and guarantees during the post-crash bailout binge.)

There is an entire class of people like this, who expect that their wise words about the world ought to always have an audience for no reason other than they possess great wealth. These men slide each morning from their unwrinkled sheets, still in their smart grey suits, ready to address their friends at CNBC, which serves as a kind of Whatsapp group chat for people with homes in the Hamptons. They go on Squawk Box, or Bloomberg Tictoc, and proselytize to the already converted that Democrats must be careful not to alienate the financial sector, or reshape the economy too much in case some guys with more money than Croesus see lower quarterly returns on their massive portfolios. Thank you so much, Mr. Moneybags, for coming on to our program to share this keen insight: The rich oppose policies that would make them less rich. Please come back anytime.

The value of asking these people what they think is supposed to be that, whether you like it or not, they hold a lot of sway over the Democratic primary process. The candidacies of Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg are fueled in large part by Wall Street donors, whose money gets massaged out at closed-door fundraisers. To the extent that this is a hard truth, it is perhaps important to know what they have planned for the rest of us. But it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you treat the financial elites who believe they should control the process as these fascinating emissaries from the world of our betters, they will continue to hold this power. Their opinions will dominate the conversation, and their preferences will simply matter more.

That is how you end up with Deval Patrick: a candidate no one asked for, advocating for policies that are already overrepresented in the field, doing things like defending private equity, and explaining that while Barack Obama attacked Bain Capital—indeed it was his principal political strategy in his 2012 re-election campaign—you never heard Deval Patrick join in, no sir! It might be baffling to the rest of us, but to people who spend their lives earning money by already having money and watching CNBC at the gym, it’s only logical to have a candidate representing Wall Street in the mix. And if you’re a cancer patient who got hauled to jail over a medical bill, and you’re feeling sick and tired of being lied to about who actually wants to help you, well—have you thought about the finance bro who might have to pay a two percent tax on their $50 million wealth? It could always be worse.