Yesterday, the House Natural Resources Committee held a hearing on Representative Deb Haaland’s Justice for Native Survivors of Sexual Violence Act, which she introduced in July with a bipartisan group of co-sponsors including Republicans Paul Cook and Tom Cole, as well as fellow Democrats Ruben Gallego and Sharice Davids. The bill would allow the law enforcement offices of tribal nations to prosecute non-tribal-citizen offenders for crimes including sexual assault, sex trafficking, and stalking.

It’s one of a handful of bills aimed at addressing the jurisdictional issues that have exacerbated the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s crisis, allowing perpetrators to walk free. Like the other proposals, it has languished in Congress for months. (The Senate version of this bill was brought by Democratic Senator Tina Smith and has similarly stalled.) Thursday’s House committee hearing was a step toward the bill being introduced to the full chamber. It also, however, featured an exchange that, more than any other in recent years, displayed just how much paternalism still exists among American conservatives, who are willing to do anything to prevent American citizens being subject to the laws of the nations they traverse.

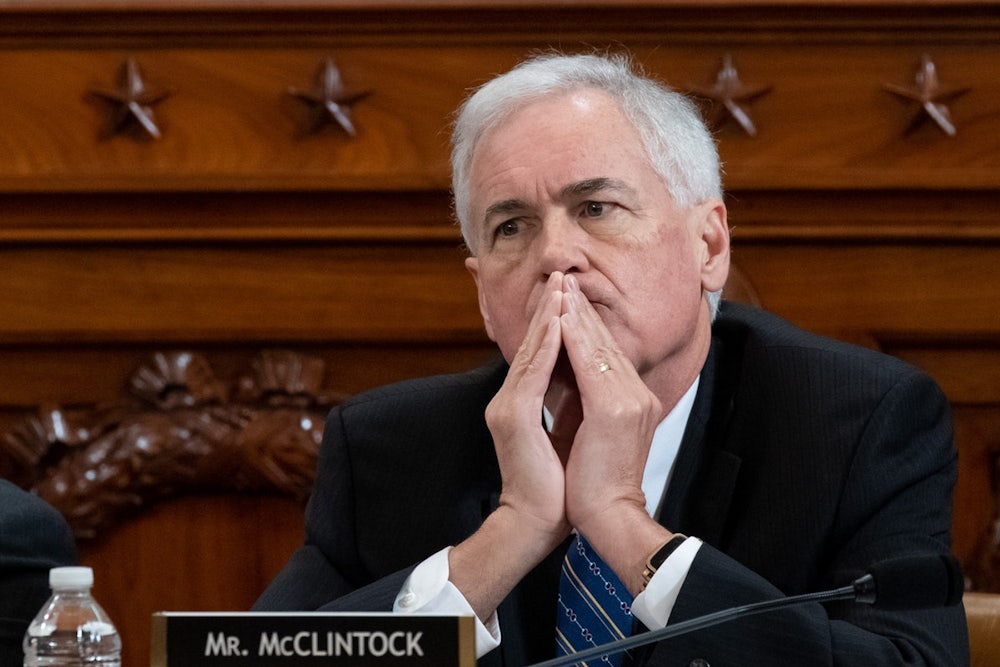

Following an opening presentation from Representative Haaland, three Republicans—Louie Gohmert, Garret Graves, and Tom McClintock—immediately questioned her about the bill. McClintock began his statement by claiming to be “a strong supporter of tribal sovereignty.” The exchange that ensued suggested the opposite.

Worried about extending tribal jurisdiction to non–tribal citizens—McClintock repeatedly used the term “members”—the California Republican rolled out a puzzling hypothetical, one that was supposedly meant to show the inherent danger of allowing tribal courts to handle crimes that occur on tribal lands. “I’m a customer that goes to a casino, and I am charged with inappropriately touching a waitress there at the casino,” McClintock said.

The normal enforcement would be I would be tried in a federal court under all due process rights and the Bill of Rights, including the right to a jury of my peers. But under this legislation, if the accusation were made, I wouldn’t be tried in a federal court but a tribal court?

McClintock then leaned on one of conservatives’ favorite talking points when it comes to legislation that would dare increase the ability of tribes to institutionally combat violence against women: that of the mistakenly charged sex offender. Wondering aloud about a case in which his hypothetical casino attender was “frivolously accused,” McClintock dived headfirst into what was ultimately his central objection to the idea of a Native-run court dealing with non-Native people. “In California, many of these tribes number a few hundred to a thousand or two members, many of them related,” he brashly stated. “I assume the jury pool would be drawn from this tight-knit community in a tribal court, without the protection to due process rights.”

Mr. McClintock and Co., welcome to Tribal Sovereignty 101.

For the uninitiated: There are 573 federally recognized tribes in the United States, and over 100 other state-recognized tribes. What that means is that within the American border exist 573 dependent domestic nations, made up of tribal governments that pass and enforce their own laws. The “dependent” facet comes into play as it relates to the U.S.’s role as a financial benefactor for a variety of services when tribes cannot back them themselves—health care, education, sometimes law enforcement, etc. This is not the result of the American government randomly deciding to graciously provide these services, but a consequence of the legally binding treaties Congress signed with these Native nations, often in exchange for land it was seizing. In many cases, Native nations fund and oversee their own court systems but are unable to police noncitizens, which is the loophole Haaland’s bill sought to address.

McClintock’s insinuation—that because a jury might be mostly or entirely made up of Native jurors, it would not adequately be able to deliver justice—is an outrageous statement and an extreme expression of privilege. Unlike white men, who have forever had the benefit of looking to a pool of jurors and to the judge’s bench and seeing themselves represented, Native people rarely have the luxury of being tried by a jury of their peers. Not only are Native women killed at rates 10 times the national average, Native people as a whole are incarcerated across the country at a rate more disproportionate to their general population makeup than any other group of people. This is the case precisely because they are not adequately represented in the legal and criminal justice fields. Yet if one were to flip the tables—not even that, but merely to stipulate that if you enter a tribal nation’s jurisdiction and commit a crime there, you have to adhere to its legal system—this is apparently worthy of hand-wringing.

Let’s be clear here: What McClintock is saying, and what an amendment later offered by Gohmert sought to codify, is that it is an act of oppression for people to be held accountable to local laws when they commit crimes in places that they visit on their own accord in order to participate in leisure activities not widely available to them on American land because of American laws. Not only is this asinine case being made, but it’s being made from the perspective of a drunk white man forcing himself on a Native woman and casino employee as he actively dodges both U.S. gambling laws and the chance of being caught acting abusively. Every statistical measure available, of course, suggests it might not be the worst thing if these predatory men believed that they would be overzealously prosecuted if they committed a crime of sexual or domestic violence. No evidence, however, suggests that this is actually the case.

McClintock tried to cover himself by then switching perspectives and saying that if he were a casino owner, he certainly wouldn’t want Haaland’s law in place, as he claimed it would drive away business. Never mind that Americans regularly flock to places outside of American legal jurisdiction, such as Cancun, for similar entertainment, rather than sitting curled in a ball in their American homes, fearing to ever leave the house lest they cede all their rights.

Representative Haaland offered a profile in patience, responding that “tribes need to be able to take these things into their own hands when they can, and we shouldn’t be a barrier to stop them from doing so.” Another highlight came when she referenced the 2017 movie Wind River, about a pair of white FBI agents who drop everything to investigate a murder on a reservation. “That never happens,” she told her Republican counterparts.

Fellow Democrats joined Haaland in correcting the record. “We’ve had this argument that’s been going on now since we stopped the annihilation of tribes in the 1970s, that we want tribal governments to be self-sustaining and sovereign,” Representative Gallego said. “The one area that we don’t let them have some sustaining sovereignty is where there are actual tribal police with tribal courts. We tell them that we do not trust them to enforce their laws and to seek justice for their tribal members,” he said. “I think this is actually closing a loophole.”

Representative Gregorio Sablan, a Democrat from the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, rebutted the idea that small communities can’t uphold legal standards. “I come from a district where our population is small. Truthfully, everybody knows everybody else,” Sablan said. “We cannot continue to hold [Indian Country] back and say certain tribes are not qualified to do the jobs of jurors.”

“These are citizens of the United States,” he continued. “That’s a jury of my peers.”

When all the talking was done, Gohmert’s amendment was defeated by a vote of 18-11, and Haaland’s bill passed 22-7. Yet again, however, the official record was stained by unnecessary fearmongering over Native people taking their lives and their justice systems into their own hands—and by the apparently terrifying specter of white Americans being answerable, like everyone else on this planet, to laws other than their own. The session provided another reminder of how comfortable some politicians feel—sitting in Congress, knowing they are on video—voicing their dismissal of sovereign nationhood, even on an issue as important as protecting women from sexual violence.