Medication abortion is incredibly common in the United States; it’s also incredibly safe. And it’s because of this relative ease and safety, in fact, that conservative states are now targeting it in the same ways they have targeted providers and clinics in recent decades: In 18 states, a provider must be physically present to prescribe abortion medication, a barrier compounded by the fact that nearly 40 percent of women in the U.S. aged 15–44 live in a county without an abortion clinic. A number of states also have laws on the books that criminalize people who terminate their own pregnancies, and “there have been at least half a dozen U.S. cases where women have been arrested and charged after attempting to self-induce an abortion using illicitly obtained abortifacients,” according to the Guttmacher Institute.

It is now 47 years after Roe v. Wade, and we are still someplace we’ve already been. But that sense of familiarity goes back even further than the landmark abortion case: 200 years ago, as medicines and tonics meant to cause abortion were made more accessible through advertising, laws targeted their use as well.

Abortion has gone from being legal to illegal in this country before, and with Roe in jeopardy, advocates for reproductive freedom have forecast a future that looks much like our past, when pills were a major part of abortion access—and an obsessive target for abortion opponents.

The story of abortion regulation and criminalization in the U.S. begins, in some ways, with the sale of abortion pills. Such open business was part of the reason states pushed to pass the first laws governing abortion in the 1820s and 1830s, according to Lauren MacIvor Thompson, historian at Georgia State University and author of the forthcoming Battle for Birth Control: Mary Dennett, Margaret Sanger, and the Rivalry That Shaped a Movement. “But they were mostly only governing the advertising and sale of abortifacient drugs.” The laws were meant to regulate, not to outlaw, abortion, she told me in an email.

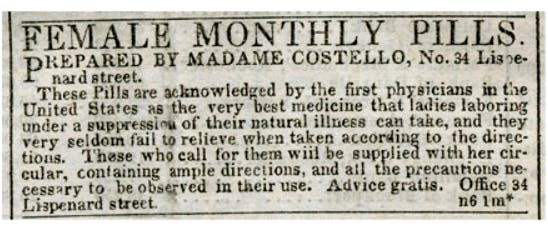

Perhaps the most notorious target of these bans was a New York woman who went by the assumed title of Madame Restell. To get around the law, abortion was advertised as a cure for “stoppage of the menses”—“which was accurate,” noted professor of journalism history Marvin Olasky, “in that the leading cause of menstrual stoppage among women of child-bearing age was pregnancy.” Restell, née Ann Lohman, was a midwife who sold abortifacient drugs in the city’s leading papers in the 1840s without using the word “abortion.” Yet her ads, Olasky wrote, were “designed to sell the idea of abortion itself.” One such ad, in The New York Herald, read:

In how many instances does the hard working father, and more especially the mother of a poor family, remain slaves throughout their lives, tugging at the oar of incessant labor, toiling but to live and living but to toil, when they might have enjoyed comfort and comparative affluence.…

Such ads proffered an illicit act for sale—one that was difficult to prosecute due to ambiguous laws and a cloud of secrecy among clients, but a crime nonetheless—and some newspaper editors refused to run them. Others defended their acceptance of the ads on the grounds that they should not be in the business of rejecting advertisements based on the profession of the advertiser. It was also good business sense, Olasky explained. He estimated that Restell’s ads could bring in $650 annually for one paper in 1839, “at a time when decent New York apartments cost $5 or $6 per month.”

These first anti-abortion laws were aimed at “the commercialization of the practice,” the historian MacIvor Thompson told me by email, “and not so much the practice of abortion itself.” At that time, she explained, people viewed abortion “as part of the universe of ‘birth control.’” The state’s interest, she wrote, was “that unregulated abortifacients or untrained practitioners might be profiting off of abortion services that were unsafe and simply killed patients outright.” (An 1827 Illinois law prohibiting the “provision of abortifacients,” was listed under “poisoning,” according to Leslie J. Reagan’s When Abortion Was a Crime.)

Dangerous providers who put profit over health were absolutely a risk—but abortion then, as today, was still safer than pregnancy and childbirth. But the regulation of abortion, too, serves a profit interest, as feminist theorist Silvia Federici has argued throughout her work. A feature of capitalism’s extension into heretofore private relations, she wrote in “On Primitive Accumulation, Globalization and Reproduction,” is “the institutionalization of the state’s control over women’s sexuality and reproductive capacity, through the criminalization of abortion and the introduction of a system of surveillance and punishment literally expropriating women from their bodies.” Women are expected to assume, consenting or not, their role producing a new generation.

Doctors were also at the forefront of pushing anti-abortion laws, most notably with the American Medical Association’s successful national campaign to criminalize abortion outright, beginning in 1858. Medical historian James Mohr argued that physicians saw those untrained, unregulated providers, like midwives, as competition. According to Mohr, doctors’ drive for anti-abortion laws was part of their quest to professionalize medicine.

An influential physician and leader of the anti-abortion campaign at the time, Horatio Storer, went beyond such arguments for professionalism. Marriages in which “conception or the birth of children is intentionally prevented,” he wrote, were “legalized prostitution, a sensual rather than a spiritual union.” A woman who refused her pregnancy was in essence a whore, selling something that was not believed to be hers in the first place.

To convince lawmakers and the public that abortion posed a risk to American society, doctors also positioned anti-abortion law as “part of an Anglo-Saxon racial project,” according to sociologists Nicola Beisel and Tamara Kay, inseparable from anti-immigration campaigns. “While laws regulating abortion would ultimately affect all women, physicians argued that middle-class, Anglo-Saxon married women were those obtaining abortions, and that their use of abortion to curtail childbearing threatened the Anglo-Saxon race,” Beisel and Kay wrote in 2004 for the American Sociological Review. Outlawing abortion, to them, was necessary to discipline white women for their failure to reproduce and to preserve white political dominance. Abortion was not regarded merely as a crime against womanhood, argued Beisel and Kay, but a crime against the state. “Physicians suggested that the moral failings of American women threatened the obliteration of the country by a tide of aliens.”

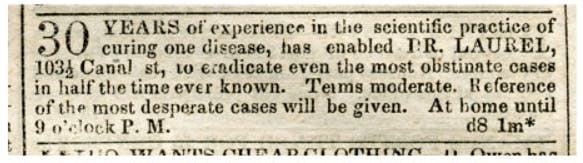

This didn’t quell the demand for abortion—which was not really the point. Neither did criminalization drive abortion fully underground. Into the 1860s and 1870s, New York readers could still learn, however euphemistically, of the alleged effects and availability of “Dr. Vlcaoli’s Italian Female Monthly Pills” or “Chichester’s English Pennyroyal Pills,” in big city and local papers alike, from the New York Evening Telegram to the Syracuse Daily Standard. People using titles like “Professor of Midwifery” or “Professor of Diseases of Women” offered “A Certain Cure,” “safe and healthy,” for “immediate removal of all special irregularities in females, with or without medicine, at one interview.”

These abortion ads, from the century in which abortion was first made a crime in the U.S., may now evoke another possible post-Roe reality. Those with means will always be able to obtain an abortion, lawful or not. Far more people will be able to control their own abortions in pill form if given access. In states with abortion laws so restrictive it may as well be fully illegal, these pills are already a common lifeline. There may not be advertisements in local newspapers, but there are networks and new forms of coded language. Madame Restell has been replaced by activists and self-trained providers operating under their own pseudonyms. No legal regime can truly end abortion. We have learned that lesson well enough before.