The day after Donald Trump’s election, Pete Buttigieg stopped by the Notre Dame campus to attend an impromptu gathering of about three dozen distraught College Democrats who had all worked on losing 2016 campaigns.

The South Bend mayor—who seemed at the time like an island of calm in a sea of Democratic despair—listened to the students and offered words of balm and hope. Steven Higgins, now a Notre Dame senior, recalled, “For me, listening to Mayor Pete on November 9 feels like decades ago, but I will always remember the way he made me feel like everything would be all right.”

Three years later, Buttigieg is the apparent winner of the Iowa caucuses, though the snafu-snarled official count is taking longer than Freudian analysis. He is probably the most unlikely serious presidential contender since the Republicans nominated utilities lawyer Wendell Willkie in 1940. But the Iowa results also illustrate how quickly political fortunes can change in 2020 when every week feels like a decade.

The Iowa caucuses were a portrait in indecision. Turnout seems to have been lower than it was in 2016, with many Democrats paralyzed by the prospect of having to choose among five serious candidates.

In fact, at the caucus I attended in Ankeny, an upscale Des Moines suburb, Andrew Wollums initially caucused as “Uncommitted” (a permissible option in Iowa) and then sat there alone and unmoving on the second round. Afterward, Wollums, who fabricates countertops, explained why he stayed put. “I didn’t feel comfortable aligning with anyone. I came close, but I couldn’t do it.”

In New Hampshire, almost no one sits on the sidelines. In 2016, more than 70 percent of the state’s Democratic voters cast ballots in the primary. What makes the New Hampshire primary so confounding is that these sophisticated New England voters have a long tradition of changing their minds at the last minute.

In 2004, a fast-deflating Howard Dean lost one-third of his hard-core supporters in Manchester (the cherished “number ones” in political parlance) in the eight days between the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. Hillary Clinton fought back tears the morning before the 2008 New Hampshire primary. That burst of vulnerability helped propel her from 10 points behind Barack Obama in the pre-primary polls to a two-point upset victory.

In fact, New Hampshire voters revel in surprises. Heralded in primary lore is Henry Cabot Lodge winning the 1964 GOP primary as a reluctant write-in candidate, while serving as Lyndon Johnson’s ambassador to South Vietnam.

Political journalists often overinflate the importance of primary debates, especially once the leading candidates are familiar to voters, and their intermural arguments (on topics like health care) have become predictable. But Friday night’s CNN debate at Saint Anselm College in Manchester may be a rare exception.

Coming out of Iowa, every leading candidate has something to prove.

After an embarrassing fourth-place finish, preceded by dreary campaign events and small crowds, Joe Biden is grappling with the reality that he won’t win the nomination through inertia. In New Hampshire on Wednesday, Biden called his Iowa performance a “gut punch” and mocked Buttigieg as “someone who’s never held an office higher than the mayor of a town of 100,000 people in Indiana.”

Biden, who failed to make it to the New Hampshire primary in his two prior presidential bids, runs the risk of seeming too desperate if he spends the entire debate on the attack. But any stumble, any groping for words, could easily revive Democratic fears that Biden is not up to a sustained campaign against Donald Trump.

Elizabeth Warren—whose “selfie lines” and widely praised organization couldn’t lift her beyond third in Iowa—is suddenly facing money problems. It is never a good sign in politics when a candidate is forced to admit, as Warren did on Wednesday, that she is pulling $350,000 in ads for upcoming contests in Nevada and South Carolina.

Even though she hails from neighboring Massachusetts, which is usually a major asset for candidates campaigning in New Hampshire (where the bulk of voters get Boston TV—and have therefore been treated to years of their commercials), Warren has not led in any primary poll since November. The question facing Warren as she approaches the debate is: How do you reboot a campaign? Warren has stumbled with this in the past; her last effort to reboot her campaign involved backpedalling on Medicare for All—a stunt that managed to offend left-wing true believers, even as it failed to win her much moderate support.

On one level, Bernie Sanders should be pleased that he attracted (based on returns from 85 percent of Iowa precincts) the most initial support in the caucuses. But tellingly, Sanders failed to win over many converts on the second round of voting, which is how Buttigieg moved ahead. This is the Bernie Barrier in the presidential race: Democrats are either for him or against him. Very few fall in the ambivalent middle. And, presumably, Sanders cannot win a nomination with a ceiling of maybe 30 percent of the vote.

More than any senator in the race, Amy Klobuchar suffered from the two weeks she lost sitting mutely in the Senate during the impeachment trial. Her rural strategy paid some dividends, since she did well in the northern tier of Iowa counties near her home state of Minnesota, but it was not enough to push her higher than fifth place.

Klobuchar now requires more than just another strong debate performance. As clichéd as it may be for a reporter to write this sentence, Klobuchar needs a breakthrough debate moment to remind Democratic voters that she remains the lone experienced, pragmatic alternative to a faltering Biden.

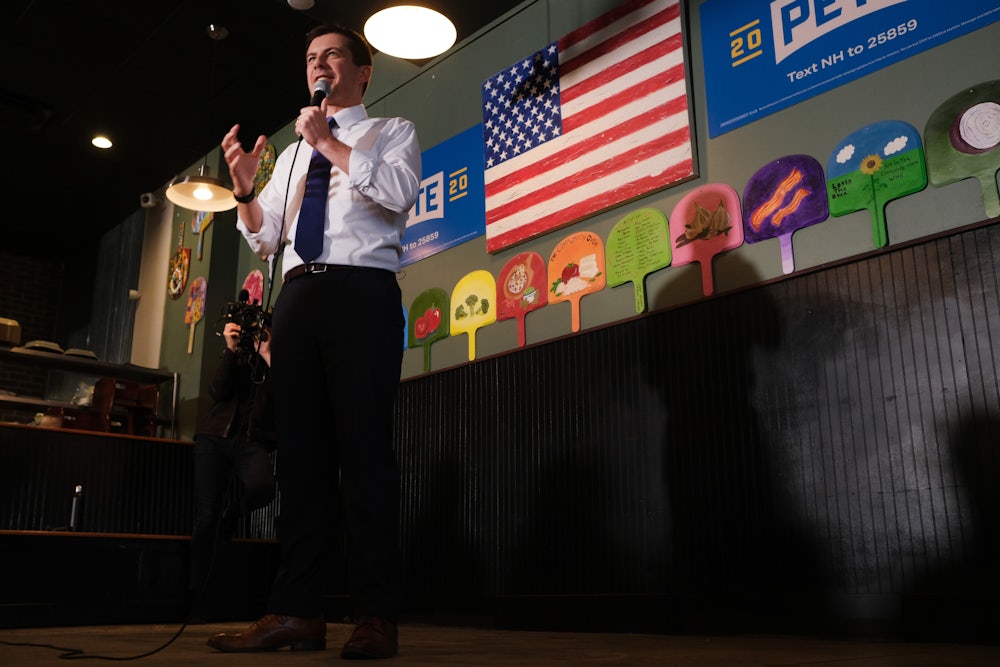

As for Buttigieg, he is entitled to feel some exasperation that the Iowa long count deprived him of a full victory lap. But now he goes into the debate with the true political mark of a winner—a bright target on his back. More than at any earlier point in the campaign, Buttigieg will have to explain (without resorting to generational bromides) why he has the experience to face Trump in November and govern successfully as president.

The only thing that offers a dash of certainty heading toward next Tuesday’s primary: The state of New Hampshire has never had a problem counting presidential primary votes.