Last week, the Las Vegas–based Culinary Union, Unite Here Local 226, found itself in the middle of a political fight after its leadership released a flyer singling out Bernie Sanders, saying that to elect him would “end Culinary Healthcare.” (“Culinary Healthcare” refers to the high-quality health insurance Nevada hospitality workers and their family members receive through the union.) The message was distributed to the union’s 60,000 members by text and email and followed another union flyer that had taken more subtle aim at Sanders and Elizabeth Warren the previous week. “We will not hand over our healthcare for promises,” that flyer read.

The drama set in motion some familiar arguments, with candidates like Pete Buttigieg jumping in to say that his health care proposal would give union members the “freedom to choose” their plan. Tom Steyer began airing an ad in Nevada that said “unions don’t like” Medicare for All and attacked its cost. Others, including many rank-and-file union members, came out to say how single-payer health care would empower unions, giving them the ability to focus on other issues at the bargaining table.

The response to that news cycle then became its own news cycle: Ryan Grim, the D.C. bureau chief at The Intercept, tweeted that Culinary Union members should “not be afraid” they’ll lose their private health insurance because “there are not 60 votes in the Senate” to ban it, “nor will there be after the election.” The next day, HuffPost reporter Matt Fuller published a story candidly laying out the barriers to passing Medicare for All in Congress: It would require not just 60 votes in the Senate but also 218 in the House, and right now the federal bills have zero Republican co-sponsors, and 145 Democrats still haven’t signed on. Even high-profile Medicare for All advocate Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez sounded a note of caution in Fuller’s piece. “A president can’t wave a magic wand and pass any legislation they want,” she said. “The worst-case scenario? We compromise deeply and we end up getting a public option. Is that a nightmare? I don’t think so.”

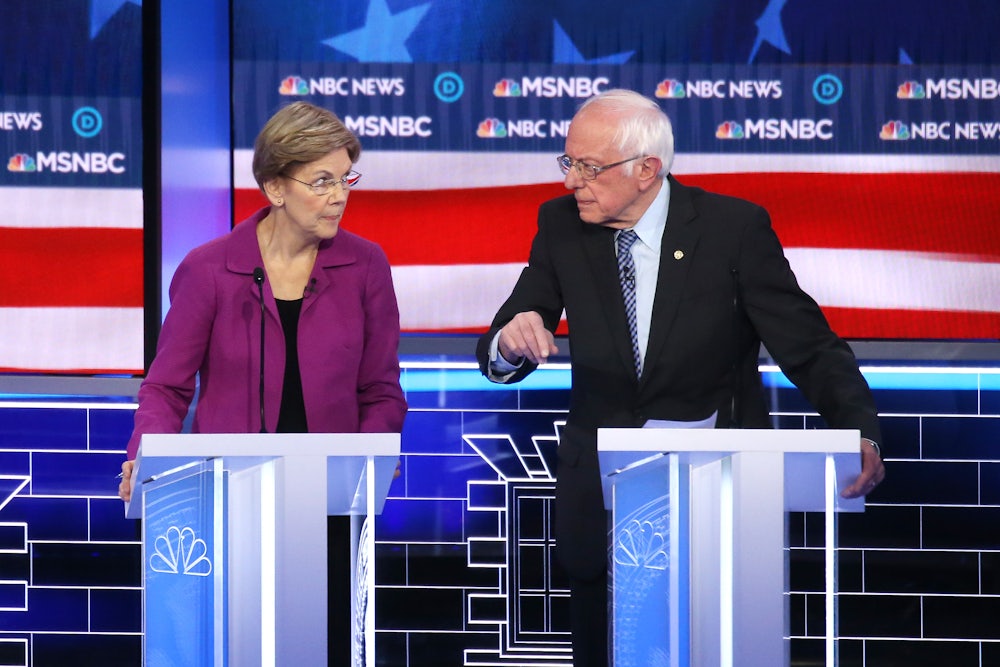

This all led to some justified grumbling from Warren supporters, who saw their candidate slammed, back in the fall, for saying there wouldn’t be enough votes in 2021 to ban private health insurance. This ongoing tension in the field was made extremely clear on Wednesday night, on the Las Vegas debate stage, when Warren criticized Sanders’s campaign for “relentlessly attack[ing] everyone who asks a question or tries to fill in details about how to actually make [Medicare for All] work.” Amy Klobuchar, who opposes Medicare for All, emphasized on stage that “two-thirds of Democratic senators are not even” signed on to Sanders’s bill and that “a bunch of the new House members who got elected see the problem with blowing up the Affordable Care Act.” Sanders, for his part, tried to assuage some concerns, promising that he would never sign a bill that would reduce union members’ health care benefits.

While opponents pick plenty of bad-faith fights over Medicare for All, these concerns are worth taking seriously. Reckoning with the political hurdle of Congress is actually quite valuable, since supporters will need to bring more people on board to push the policy forward. As Sara Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants and a backer of single-payer, put it after the Culinary Union dustup: “If you are not approaching this as an organizer and building a supermajority for this change, it’s not going to happen.”

At this point, it’s fairly uncontroversial to say that most people don’t really like the private insurance status quo, which can trap us in jobs we hate, keep us from getting the care we need, and has premiums that grow more costly each year as the benefits grow increasingly meager. But people are justifiably scared of getting sick or hurt and being left in a situation that may be worse than the one in which they currently find themselves. When considering these fears in the context of Medicare for All, advocates often underestimate just how distrustful people are of politicians, including Democrats. (According to Gallup’s annual poll, 45 percent of Democrats said they had trust in Congress, and just 33 percent of independents said the same.)

So it might not be so much that people—in unions or otherwise—don’t support Medicare for All as that they don’t trust elected officials to make it happen. This isn’t a phenomenon unique to health care debates, and back in January, New York Times reporter Astead Herndon took a look at the skepticism and doubt black voters were voicing about the detailed platforms of presidential hopefuls like Warren, Sanders, and Buttigieg. “Plans and rhetoric are one thing, but to trust a candidate to deliver—or the government at all—is entirely another,” Herndon wrote. “In a community all too familiar with legal discrimination and unequal access to public services, believing in ‘big, structural change,’ as Ms. Warren likes to call it, is a gamble.”

Sanders, according to several new polls issued this week, is the current front-runner for the Democratic nomination. That’s a huge boon for the single-payer movement. (As is a new study out last weekend from Yale epidemiologists that found Medicare for All would save $450 billion and prevent 68,000 unnecessary deaths every year.) Polls also show that voters generally trust Bernie Sanders; people think he’s honest and says what he means. His long record of standing with labor unions and advocating for single-payer health insurance is also well documented.

But because the success of Medicare for All will rest primarily on Congress, many voters are likely asking themselves: Can I trust the Democrats in Congress to pass the bill as written? Do they also seem willing to fight for me? Do they have a record of fighting for workers during legislative negotiations? What about Republicans? The answers to those questions are much, much more mixed.

There’s a lot a savvy president can do in terms of agenda-setting, but there’s a lot a recalcitrant or dysfunctional Congress can do to hobble a president’s agenda. Trump was able to get through some of his biggest initiatives, like tax reform and trade, largely thanks to the unusual willingness Democrats showed in working with him. Voters should know by now that Republicans cannot be counted on to work with Democrats in return.

Earlier this week, when asked about Ocasio-Cortez’s public option remarks, Sanders told CNN’s Anderson Cooper that his Medicare for All bill is “already a compromise.” That makes clear sense to me, but while there will be no shortage of disingenuous opponents, advocates should understand that not all those who express fear or doubt are trolls. They don’t back “needless death,” as some supporters like to charge, because they’re worried about conservative Democrats like Kyrsten Sinema or Joe Manchin, who won’t face reelection until 2024. Democrats like these will be an obstacle to enacting progressive policy. It’s on the Medicare for All movement to organize those who are nervous or skeptical and to build a coalition strong enough to achieve its goals.

No one knows what health care will look like in five years—but what we do know is that five years ago, no one was talking about single-payer. Conventional wisdom in D.C changes fast. That we can trust.