Among the many ways the pundit class has sought to understand the Democratic primary field, from its early overpopulated days to the substantially winnowed group of contenders we have now, the most durable involves the concept of “lanes.” Bernie Sanders, who will go into the South Carolina primary hoping to maintain his position as the front-runner, is said to occupy the “progressive” lane; the majority of his opponents reside in a corresponding “centrist” or “establishment” lane. One of the theories for why Sanders is winning is that the many candidates occupying the “moderate” lane—Joe Biden, Michael Bloomberg, Amy Klobuchar, Pete Buttigieg—are cannibalizing the available moderate vote. This notion happens to be a nifty analogue to the 2016 Republican primary, in which a collective action problem among Donald Trump’s opponents secured the nomination for the reality-television mogul. As always, in politics, the new thing looks like the last thing.

Amid this noisy friction between ideological factions, Elizabeth Warren has been the odd person out. Like Sanders, she is seen to occupy the progressive lane, absorbing some portion of the voters who might otherwise swing his way. Warren, however, is far off the front-runner pace. Pundit logic holds that for her to forge a path to the nomination at this late hour, she must poach as much of Sanders’s support as she can. As long as Sanders is in the ascendant, Warren’s star cannot rise.

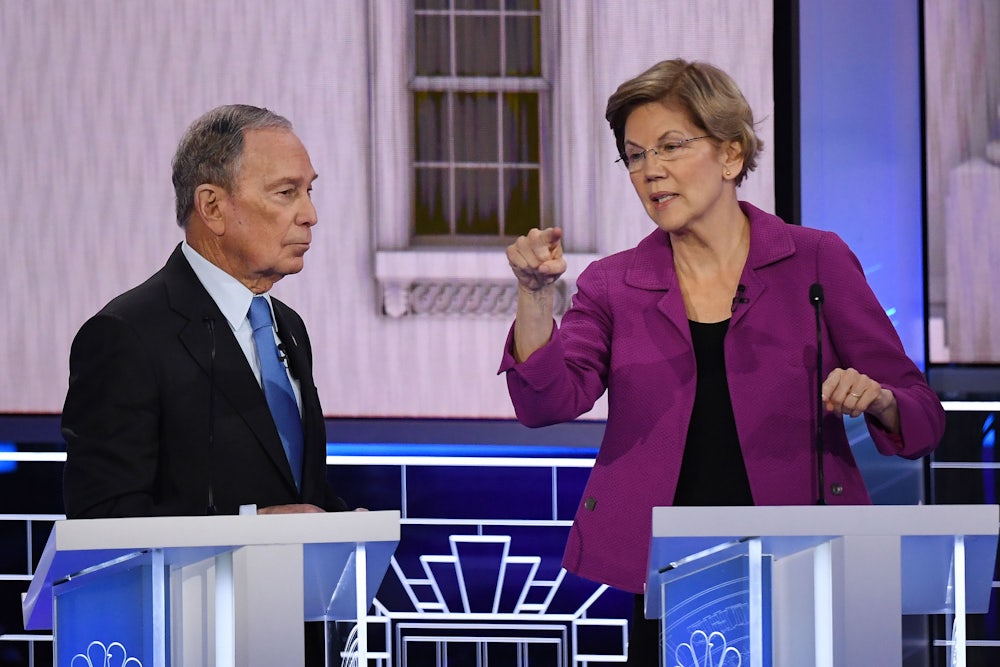

And yet she has spent the bulk of her time in two consecutive debates lustily assailing Michael Bloomberg, to the bafflement of political observers. “Warren is now on CNN clobbering Bloomberg on NDAs like a prosecutor making a closing argument with nary [a] word about Sanders, who you might think was her biggest political problem,” tweeted political analyst Jeff Greenfield. This take was seconded by eternal Democratic consultant James Carville, who told his cable news audience, “Elizabeth Warren gives you the impression that she’d rather beat Bloomberg than win herself.”

One thing that seems to have gone unappreciated here is that Warren has, in fact, endeavored to articulate how she’d be a more effective president than Sanders. In one of last night’s debate’s quieter moments, she went on at length about how she would “make a better president than [Sanders],” characterizing herself as uniquely devoted to “digging into details” and being more clear-eyed about the difficulty of enacting a progressive agenda. “Bernie and I both want to see universal health care,” Warren said, “but Bernie’s plan doesn’t explain how to get there, doesn’t show how we’re going to get enough allies into it, and doesn’t show enough about how we’re going to pay for it. I dug in. I did the work. And then Bernie’s team trashed me for it.”

It’s a starkly articulated broadside, one that substantially complicates the narrative that provides the maximally tawdry reason for her treating Sanders with kid gloves: that doing so keeps alive the hope that she might, in the event of his nomination, serve as his running mate.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that Warren’s attacks on Bloomberg have been spicier and more relentless than her occasional jabs at her ideological cousin. There’s a perfectly logical explanation for this seeming paradox, which is that Warren’s ends-means calculation is less vulgar than the typical Democratic candidate’s. Simply put, she’d prefer to be the candidate to defeat Donald Trump, but failing that, she would prefer to see Donald Trump defeated.

To Warren’s mind, this necessitates driving Bloomberg from the race. “I don’t care how much money Mayor Bloomberg has, the core of the Democratic Party will never trust him,” Warren said last night. “And the fact that he cannot earn the trust of the core of the Democratic Party means he is the riskiest candidate standing on this stage.” This is not an unreasonable assessment. Bloomberg is little known outside of New York City and Acela-stan media aeries. He is largely unvetted and untested and, in consecutive televised appearances, this has been rivetingly apparent.

But beyond that, there is Donald Trump and his playbook for reelection to consider. The president differs from many chief executives in that, during his first four years, he’s made little effort to bring in new voters to his coalition. The failure to do so means that we are likely to see a retread of the strategy by which he reached the presidency in the first place: He’ll make robust, red-meat overtures to excite his base while deploying targeted social media encounters designed to engender a hopeless despondency within the Democratic electorate.

In Bloomberg, he would draw the ideal opponent, an effete Manhattan billionaire who, unlike Trump, has not assumed the mantle of a class traitor; who has endeavored to take everyone’s guns and sodas away; who has a record of antagonizing key constituencies within the Democratic base—women and people of color—through his personal behavior, the corporate culture he cultivated, and the policies he’s enacted and defended. Trump wouldn’t have to resort to convoluted conspiracy theories, such as the wild Burisma-related yarn he’s clearly engineered to savage Joe Biden, to accomplish his goal of reelection. Bloomberg’s actual record is sufficient to the task, as is that lack of trust among Democrats of which Warren has sounded an alarm.

Warren is hardly the only Democrat in the field who has raised these concerns about the interloper in their midst. At the previous debate in Las Vegas, each of the contenders articulated reasons why Bloomberg would be unfit to carry the party banner in November. In this way, the Democratic candidates have made a clean break with their party’s chieftains, who bent the rules to allow Bloomberg to join the debates in the first place—rules which, it should be said, were deployed to chase several candidates, all with a richer history of fealty to the Democratic Party’s cause, from the race.

Looking down the road, this tension between the candidates and their party’s elites portends a deeper danger. Should the extant trends in polling and projections hold, Bloomberg may not be able to accrue the necessary number of delegates to claim the nomination outright. He may, however, be viable enough to prevent anyone else from doing the same. Bloomberg’s path to the nomination would thus run through a contested Democratic convention, in which the same machers who put their thumbs on the scales to benefit Bloomberg’s candidacy hand him the nomination. Should that occur, Sanders’s supporters will not be the only ones aggrieved by the outcome. In this scenario, the Democratic Party unwittingly provides President Trump’s turnout-depression machine with the fuel it needs to run forever. And the consequences for the Democratic Party, should Bloomberg lose after all of this, are dire. How would the party survive losing this all-in wager on a candidate who is not even a Democrat?

This is how the Democratic Party explodes. And while one can only speculate as to whether Warren has gamed all of this out, between her and Sanders—the two candidates in the so-called progressive lane—only Warren is known to be devoted enough to the Democratic Party as an institution to recognize that the danger Bloomberg poses may supersede her own electoral ambitions. In the end, the answer to the question on the minds of befuddled pundits may be a simple one. She loves her party, she loves her country, and she recognizes that pulverizing Bloomberg is a necessary act; a patriotic endeavor.