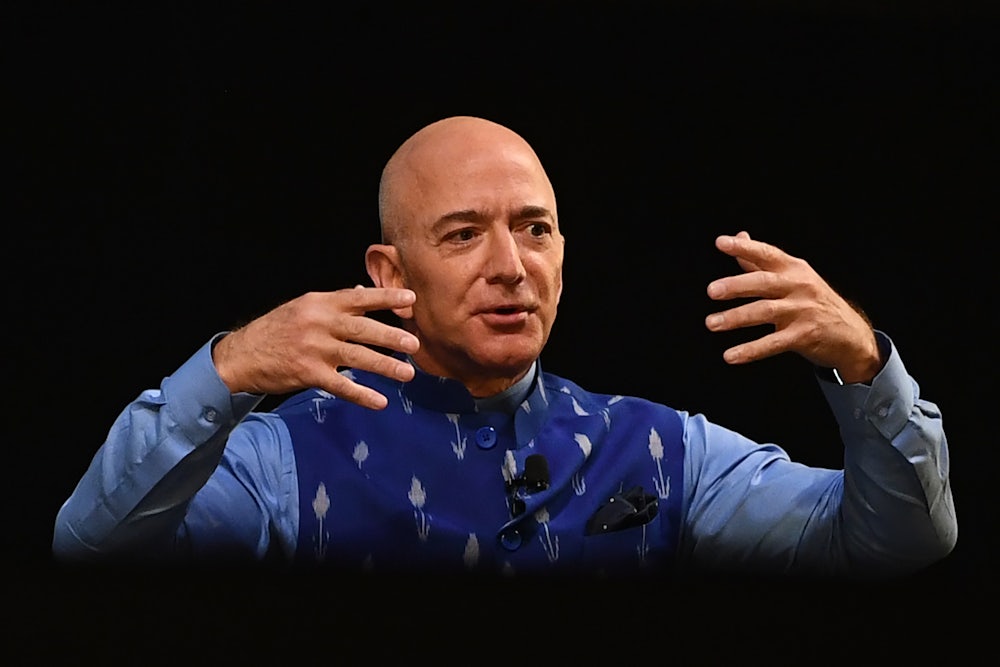

At a press conference on Monday, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that the state would begin to manufacture its own hand sanitizer at the cost of $6 a gallon, as part of a broader effort to contain the coronavirus epidemic that is currently causing widespread disruptions across the United States. The product, called NYS Clean, is currently being kept off the private market—it’s planned for use in schools, prisons, and public transportation vehicles. However, Cuomo issued a warning: “To Purell and Mr. Amazon and Mr. Ebay, if you continue the price gouging, we will introduce our product, which is superior,” he said. “So stop the price gouging.”

Cuomo’s accusation did not emerge from a vacuum. In late February, Amazon made news when it made a show of warning third-party sellers on its online marketplace that price gouging on products that have been in high demand ever since the coronavirus took root—surgical masks, hand sanitizer, and similar hygiene-centered goods—would not be tolerated. Isolated, early reports suggested some of those sellers were upping prices for in-demand products by as much as four times the usual cost. At one time last week, the website reportedly listed a box of small bottles of Purell hand sanitizer that usually sells for $10 at $400.

Scandalized by the inhuman markup on sanitizers, Amazon pledged its innocence in a public statement: “There is no place for price gouging on Amazon.” The company went on to promise to intensify its monitoring of third-party “bad actors,” on whom it placed the blame. However, according to a new analysis by the consumer watchdog group U.S. PIRG Education Fund, in addition to third-party gouging, almost one in six of the millions of products sold directly by Amazon itself had prices spiked 50 percent higher than a recent 90-day average.

The implications of the study appear damning: One of the richest, most powerful corporations in the world is profiting from and taking advantage of fearful consumers desperately trying to protect themselves and the people for whom they are responsible from an epidemic. It raises serious doubts about how rigorous Amazon has been about systemically ensuring that neither its employees nor its algorithms are allowing buyers to be unethically overcharged. And its findings suggest that Amazon may, in fact, be in violation of several states’ anti-price-gouging laws. Lawmakers reluctant to take on the company may be forced to do more than issue stern warnings.

At the very least, this evidence of gouged prices directly from Amazon seems to violate the company’s own “Marketplace Fair Pricing Policy,” which guards against “pricing practices that harm customer trust” and threatens consequences for listing “a price on a product or service that is significantly higher than recent prices offered on or off Amazon.” U.S. PIRG found that, in recent weeks, the average price of the hand sanitizer and mask products in their study was 220 percent higher than their 90-day average.

“We’ve known from past instances, like hurricanes, that price gouging has occurred on Amazon and other platforms,” said Adam Garber, who led the analysis for U.S. PIRG. But because this public crisis is international, he said, its effects appear to be significantly worse. “We realized in February there was going to be a run on crucial supplies.”

The group reached its conclusions by tracking the prices of products that were likely to be in demand after the World Health Organization declared a coronavirus-related global health emergency on January 30 and comparing those numbers to an average of their price performance across 90 days, from December 1 to February 29. The findings, Garber said, are actually conservative estimates because their reported average includes sales in the month of February, after the WHO declaration that spooked countless people into stockpiling. What consumers might see on a day-to-day basis is often worse—such as $459 for a one-ounce bottle of boutique-looking hand sanitizer that, as of Tuesday, would arrive sometime in April with free shipping. More than half of the in-demand products analyzed had price spikes over 50 percent.

“The fair-pricing policies and efforts Amazon were using were not sufficient to protect their shoppers,” said Garber. “They needed to enact strong, proactive protections to prevent those prices from ever appearing on a computer screen.”

One of the deep complexities for both reporters and watchdogs trying to hold Amazon accountable amid the coronavirus outbreak—or any similar crisis that may emerge in the future—is that it is difficult to determine just how much of Amazon’s market is set by algorithms and how much is derived by the collective actions of individual sellers or the relatively invisible hand of Amazon employees.

Experts suspect that most products sold directly by Amazon have prices set largely by algorithms. But consumer advocates argue that an online platform as large, powerful, and centrally controlled as Amazon can and should put limits on price increases in place so that exorbitant price spikes—such as a single container of Lysol wipes selling for $60 or a two-liter bottle of Purell selling for $149 (when a similar product was recently listed at $29.21 on Walmart)—never make it to the website in the first place. As it stands, there have now been several weeks in which frightened consumers in unknown numbers have likely bitten the bullet and paid many times more for products than they would or should have in periods of non-crisis.

One possible solution to guard against items receiving unethically high markups is for Amazon to ensure that every product listed online is “human-approved.” That said, it might be naïve to count on an enormous, profit-motivated corporation to follow humane inclinations. To fully protect consumers, the government may have to make use of the space offered by the law, and political will, to take action. New York State, for example, has a price-gouging law that “prohibits merchants from taking unfair advantage of consumers by selling goods or services that are ‘vital to the health, safety or welfare of consumers’ for an ‘unconscionably excessive price’ during an abnormal disruption of the market place or state of emergency.”

Governor Cuomo declared a state of emergency over the weekend. And although those buying surgical masks are unlikely to find sympathy from government officials at any level—virtually all of whom have beseeched consumers not to hoard them at the expense of the medical professionals who are in short supply of them—the apparent gouging of other sanitizing and disinfecting products may garner a state response.

Garber, who gives Amazon grudging credit for its initial “whack-a-mole actions,” said that state attorneys general should “investigate whether these activities violate their price-gouging statutes and use it as an opportunity to prevent something like this happening again.”

In the times we call normal, there is a hushed caution about taking legal actions against major multinational corporations like Amazon, which often seem like nation-states unto themselves. Yet amid an unprecedented crisis—in which the notions of risking business partnerships and private-sector profitability in order to protect the common good are suddenly on the minds of even middle-of-the-road politicians—consumers might just have a chance at genuine recourse.