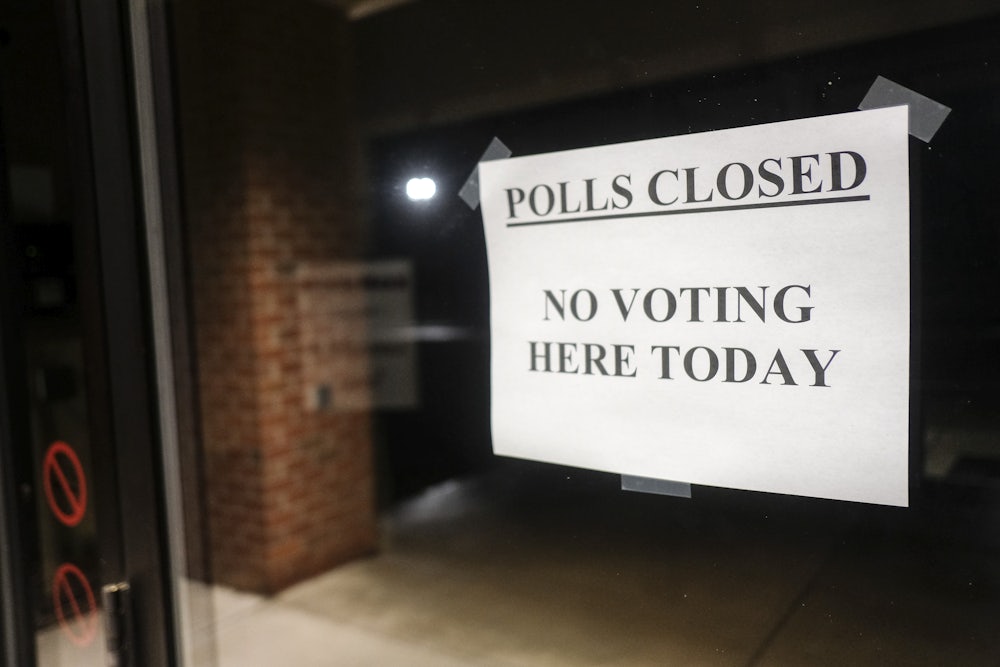

Countless Americans have died for democracy and the right to vote, but none of them should now have to risk death to exercise it. The coronavirus pandemic led Ohio Governor Mike DeWine and other top state officials to shut down polling places statewide on Monday night, effectively canceling the state’s Tuesday primary elections for now. “During this time when we face an unprecedented public health crisis, to conduct an election tomorrow would force poll workers and voters to place themselves at an unacceptable risk of contracting coronavirus,” he said.

The process was hardly neat and orderly. DeWine first tried on Monday to get the election delayed until June but was rebuffed by a county judge who ordered the vote to take place on time. Ohio Capital Journal reported that county boards of election had already told poll workers to stay home when the ruling came down on Monday evening. A few hours later, the state’s top health official said she would be closing down polling places as part of a state of emergency. The state supreme court then rejected a challenge to the order early Tuesday morning.

There is no reason to believe DeWine was acting in bad faith or with malice; among governors, his response to the pandemic has been seen as the gold standard. But ham-fisted efforts to shut down elections should trouble all Americans, no matter how justified they may be. Almost half of the states are slated to hold primary elections in the next few months, and all of them will be holding the general election in November. Ohio’s experience shows why every state legislature must enact a universal vote-by-mail option as quickly as possible, along with whatever other steps are necessary to safeguard the American democratic process.

U.S. elections are unusually vulnerable to disruption by a pandemic in their current form. Even in the best of circumstances, voters in many states can face long periods of standing in line with their neighbors. Older Americans—the highest-risk group for the coronavirus—disproportionately take part in the process. Voters must share various types of equipment, like voting machines, in common, which is a nightmare from a personal hygiene perspective. And polling places are also typically staffed by a small army of volunteer poll workers. Since most elections are held on Tuesday, those volunteers are typically retirees who don’t need to take time off work to supervise the process.

“The only thing more important than a free and fair election is the health and safety of Ohioans,” DeWine said on Monday night in a joint statement with Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose. “The Ohio Department of Health and the CDC have advised against anyone gathering in groups larger than 50 people, which will occur if the election goes forward. Additionally, Ohioans over 65 and those with certain health conditions have been advised to limit their nonessential contact with others, affecting their ability to vote or serve as poll workers.”

Since many Americans would likely stay home rather than risk exposing themselves to infection, especially for a mere primary election, Ohio officials said that holding the election on Tuesday would only undermine it. “Logistically, under these extraordinary circumstances, it simply isn’t possible to hold an election tomorrow that will be considered legitimate by Ohioans,” DeWine and LaRose said. “They mustn’t be forced to choose between their health and exercising their constitutional rights.”

Three other states—Arizona, Illinois, and Florida—are holding their elections on Tuesday as planned. The pandemic’s effect on turnout isn’t yet clear. But there have been other signs of disruption along the way. State officials in Arizona closed 78 polling places in Maricopa County, the most populous county in the state, because they lacked the cleaning supplies to keep them open. Maricopa County recorder Adrian Fontes responded last week by announcing he would mail ballots to all registered Democrats in the state. Attorney General Mark Brnovich and Secretary of State Katie Hobbs said the maneuver would violate state law, and a judge soon quashed it.

In Illinois, The Chicago Tribune relayed accounts of extremely low turnout at some polling places and voters being turned away from other understaffed locations. “Is the low turnout a blessing since some election judges didn’t turn up?” a reporter asked Jim Allen, the spokesman for the Chicago Board of Elections, at a Tuesday morning press conference. “I would never call low turnout a blessing,” he replied. “I would call conducting an election in the midst of a global pandemic a curse.”

Allen also told reporters that the board had recommended switching from in-person voting to an all-mail election to Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker, but he rejected the option. That prompted a sharp rebuke from Pritzker, who released a statement criticizing those who had “shirked their responsibility” while others had stepped up. “The governor cannot unilaterally cancel or delay an election,” Pritzker’s office said. “Elections are the cornerstone of our democracy, and we could not risk confusion and disenfranchisement in the courts. No one is saying this is a perfect solution. We have no perfect solutions at the moment. We only have [the] least bad solutions.”

Other states with less imminent elections have found better solutions. The best path forward would be for states to adopt universal vote-by-mail laws and delay their primaries until those systems are ready. In addition to Ohio’s ad hoc delay, four states—Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Maryland—have delayed their primaries until June in response to the pandemic. New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy is reportedly considering a plan to exclusively vote by mail for the state’s April and May local elections.

There is also movement at the federal level. Last week, Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar and Oregon Senator Ron Wyden introduced a bill that they said would allow no-excuse voting by mail and expanded in-person absentee voting in all 50 states. The Brennan Center for Justice, a nonprofit organization that focuses on democratic reforms, released a comprehensive plan to shield American elections from the pandemic. Among its proposals were a universal vote-by mail option, expanded online registration, and transparency campaigns to educate voters about rule changes.

The pandemic is already poised to be the greatest disruption to American elections since the Reconstruction era. But there’s a silver lining: timing. States have broad flexibility to adjust their calendars for presidential primaries as well as state and local elections. There are still six months to take steps to ensure the November elections can function as well. The only question is whether state lawmakers will use that time wisely to protect American democracy—and the voters who make it possible.