In early April 1992, a news headline in The Wall Street Journal captured the depressed mood surrounding a certain presumptive presidential nominee: “Democratic Leaders Resignedly Begin to Rally Around Clinton for President.”

Resignedly.

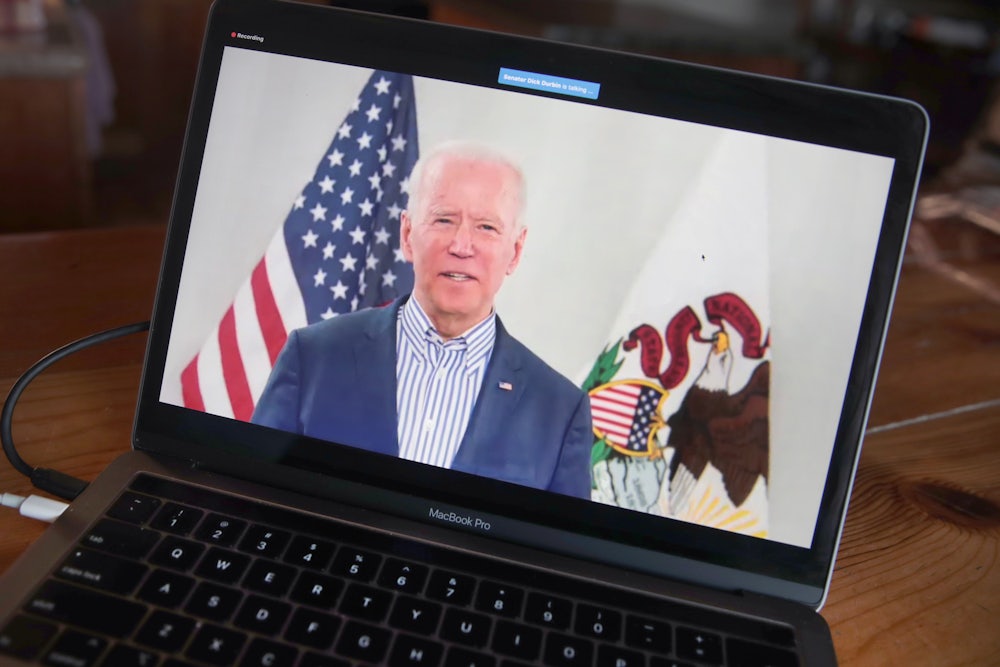

Now many Democrats are resignedly watching Joe Biden, worried that his uninspired telecasts from his Delaware basement could give Donald Trump another four years in the White House. No matter how hard his campaign aides worked to make the bookcase and lamp behind Biden’s desk look like a backdrop from a normal TV studio, there is a slapdash government-in-exile feel to the whole operation.

While basement-bound, Biden has done TV interview after TV interview, even launching a new podcast, but none of those efforts have made a significant imprint on the news cycle. The cable networks are broadcasting Donald Trump’s cloud-cuckoo-land daily briefings filled with imaginary Covid-19 cures and mythical supplies of coronavirus tests. And the most forceful Democratic responses are coming not from the presumptive nominee but from such embattled governors as Andrew Cuomo and Gretchen Whitmer.

In truth, Biden does display a presidential level of empathy for the sick, the suffering, and the fearful. At the end of an otherwise forgettable town meeting that was livestreamed to families and children on Sunday night, Biden offered moving words about loss and tragedy: “A lot of people are hurting. A lot of people will be hurt when this is over. And we’ve got to make them whole. We can. We can. That’s what we do in the United States.”

That moment may not be headline material. But for the handful of up-for-grabs-in-November voters who were watching, it was a reminder that Biden actually does feel their pain. Unlike Bill Clinton, Biden reacts to tragedy not with a bite-your-lower-lip act but rather with the hard-earned emotion of a man who has lost a great deal in life.

What the Democrats fretting about Biden’s lackluster TV performances fail to understand is that virtually every presidential candidate spends weeks—sometimes months—wandering in the wilderness after wrapping up the nomination. After the tension of the early primaries, everything comes to a grinding halt once there is a de facto nominee. Suddenly, the only one surefire way to make news is to announce a vice-presidential running mate. And that banner headline is traditionally reserved for the days leading up to the convention or for the convention itself.

Since the last two contested Democratic presidential races stretched on into June, many partisans forget the disadvantages that come with ending nomination fights too soon. Barack Obama in 2008 and Hillary Clinton in 2016 both had a strong rationale to keep campaigning until the conclusion of the primaries. In both election cycles, it was easy to go from celebrating their nominations to launching the intense speculation about their running mates.

Now that the only drama left in the Democratic race is taking place in Bernie Sanders’s mind as he grudgingly accepts the inevitable, Biden has more than four months to fill until the delayed Democratic convention. An out-of-nowhere VP choice might be enough to generate a boomlet of media attention, but there are limited options. By announcing that his running mate will be a woman, Biden is left sorting through an obvious list of worthy contenders, such as Whitmer or Senators Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, and Elizabeth Warren.

Although Democrats spending their home quarantines sitting on window ledges high above the ground may find this hard to believe, Biden is actually in much better shape than many prior nominees who also wrapped things up in the early spring.

In 1996, in the middle of May, Majority Leader Bob Dole choked back tears as he resigned from the Senate that he loved in a desperate effort to reshape the news cycle. As The New York Times reported at the time, “His political aides gloomily calculated that it had been two weeks since they had seen him portrayed in any other setting than the Senate floor—and that was in a bathing suit walking on the beach in Florida.”

In 2000, Vice President Al Gore had locked up the nomination on Super Tuesday. But a month later, he was floundering. Liberal Wall Street Journal columnist Al Hunt on April 6 called it “depressing” that the election was still 213 days away. Elsewhere, there was considerable analysis of the newly buff VP’s clothes and physique. A Washington Post story on April 9 zeroed in on how campaign aides believed that “Gore’s decision to don cowboy boots and casual garb [and] his leaner frame … have significant consequences in how he is perceived as a potential president.”

At this point in 2004, John Kerry had many of the same problems as Gore, although the Massachusetts senator had the excuse of recovering from prostate surgery. Media coverage during the second week of April focused on such gossipy topics as a bitter battle between two Kerry media consultants over fees and Democratic fears that the release of Bill Clinton’s memoirs would revive talk of the presidential sexual scandals that led to impeachment.

Biden boasts advantages that some of his predecessors lacked at this point in the calendar. After nearly a half-century in public life in Washington, the former vice president doesn’t have to worry about introducing himself to the American people. And in the midst of a pandemic, voters already know that their lives are on the ballot in November—even without Biden resorting to bitter attacks on Trump.

After finishing fourth in Iowa and fifth in New Hampshire, Biden has seen in his own campaign how political fortunes can change overnight. But then he always knew the value of patience in politics. In April 1992, Biden remarked on how quickly Clinton had resurrected his political fortunes: “Ten days ago it was ‘This man’s dead,’” he told The Wall Street Journal. “Now it’s ‘My God, he’s still walking.’ I think the guy’s a helluva candidate.”

Biden undoubtedly still remembers that in June 1992, Clinton—that “helluva candidate”—was running a distant third in the polls behind both Ross Perot and George H.W. Bush. Of course, in November, Clinton romped home with 370 electoral votes. Even before the pace of politics accelerated with cable TV news and social media, it was a long, long while from April to November.